Rogers Writers’ Trust: Spotlight on Jen Neale

We asked the 2018 nominees: Who are you writing for, who is your imagined or intended reader?

Share

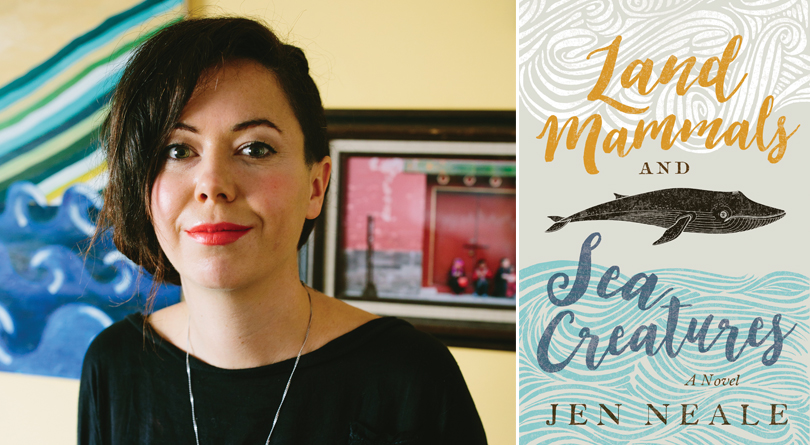

Jen Neale is nominated for the Rogers Writers’ Trust Fiction Prize for her novel Land Mammals and Sea Creatures, admired by the prize jury for the way it stitched together “the beautiful and the vile, fish guts and human frailties,” in her “salty tale of port-town dysfunction and universal pain.” The winner will be announced at the Writers’ Trust Awards ceremony in Toronto on November 7. The winner receives $50,000. Each nominee receives $5,000. During the weeks leading up to the event, Maclean’s will publish an excerpt from each shortlisted writer, along with their answer to this one question: Who are you writing for, who is your imagined or intended reader? Here is Neale’s response.

To have imagined a reader for Land Mammals and Sea Creatures, I would have had to first imagine its being published. That’s a little treat to savour with a first book, I think—the ability to create it completely within the confines of your own brain, and ignore the reality that someday people may read it.Since the book came out, I’ve thought more about who the right reader is. Likely it’s someone who doesn’t mind inexplicable events happening next to ordinary ones, and who enjoys a dose of darkness with their absurdity.

Land Mammals and Sea Creaturesby Jen Neale. Copyright © 2018 Jen Neale. Published by ECW Press Limited, www.ecwpress.com. Reproduced by arrangement with the publisher. All rights reserved.

The whale’s smooth skin surfed above the waves, its torpedo-shaped face just under the surface. The whale exhaled again, sending flecks of mist against their faces and filling their nostrils with the medicinal stench of its breath.

Ian looked to Marty for help. Save his poor baby boat. The whale ’s back grazed the farthest reach of their fishing lines and their bobbers were swallowed by the waves.

The three of them held tight to the railing and rope ties. Julie looked over at her father. He had a wet sheen along his lower lids. Under his breath, Ian said, “Not my boat, not my boat.” They all fell silent and waited for the impact. Julie stared down and counted the splashes against the hull. One . . . two . . . three . . . four. The world was devoid of sound except for the slap of waves and the gurgle of upturned water that followed the whale ’s progress.

Julie had the urge to jump over the railing and ride the whale to the bottom of the sea, swinging a seaweed cowboy hat over her head.

Just before its nose reached the hull, it began to dive. As the whale slid down, Julie held her breath and closed her eyes. The boat leaned starboard as the great mass passed underneath. Her daily life, being home in Marty’s half-dilapidated bungalow, had consisted of grey mornings eating cold eggs out of a pan and daytime television marathons. Even if I die . . . she thought.

Julie opened her eyes and watched as the mast returned to centre.

“Where ’s she going?” Ian’s grip on the railing had released but the parental look of concern stayed.

Julie tasted blood in her spit. She turned to her father. “Marty, I think she ’s beaching.”

“I don’t think so, kiddo.”

Another massive plume rose from the whale as it accelerated toward the shoreline. Rocks jutted from the water around the beach at Tallicurn.

The figure on the beach had waded farther out. One of their hands held a cigarette.

The smell of gasoline flooded the air as Ian started the engine and manoeuvered the boat to pursue the whale.

The individual shapes of the spruce and shore pines came into focus as the boat chugged closer to the shore. A bald eagle soared out from the evergreens with two ravens attacking its tail feathers.

Ian yelled over the sound of the engine. “She’s beaching!” Marty nodded. “Maybe we can steer her back.”

“In this piece of shit?” Julie asked. A look of hurt crossed Ian’s face.

A stirred line of silt illuminated the whale ’s route from boat to beach. Julie begged the blue to come to its senses. She pictured herself on her knees at the bottom, an air traffic—water traffic—controller, waving an orange flag. It’s all death and seagulls this way, Whale. Here’s a card for a suicide prevention hotline. But she spoke in a high-pitched language incompatible with the whale’s low drumming pulses.

The beast came up for another breath, its tail now too weak to rise above the waves. The sandbars came one after another and brought the whale closer to the dry summer air.

Ian killed the engine and came back onto the deck. The boat bobbed and swayed.

Marty voice was a child’s. “She’ll turn back.”

Seagulls screamed louder. The blue ’s breaths came more frequently but shot lower into the air. Finally its back was forced to stay above the surface.

Ian stood like a Renaissance-era navigator at the front of his boat, hand shielding his eyes.

“It’s happening,” he said, and Marty nodded. The whale had somehow disappointed Ian by beelining for shore. Marty rose and put his prosthesis on Ian’s shoulder.

The whale, with a last push, reached the shallows. It emerged from the water past its eyes and slid along the sand until finally, as its last motion, it rolled sixty degrees onto its right side, its tail still curled into deeper water. A freight train derailing, it folded in on itself, crumpled by its own mass and speed. Waves lapped around the whale’s bottom fin. Its length took up half the shoreline and blocked the view of the orange tent and the spruce. Out of the water, its form flattened against the sand. A deflated inner tube.

The two men stood in a silent vigil, their shoulders dropped low, while Julie flopped down on the lawn chair.