Scotiabank Giller Prize shortlist carries plenty of experience

The Giller shortlist leans towards veteran authors and literary-psychological pyrotechnics

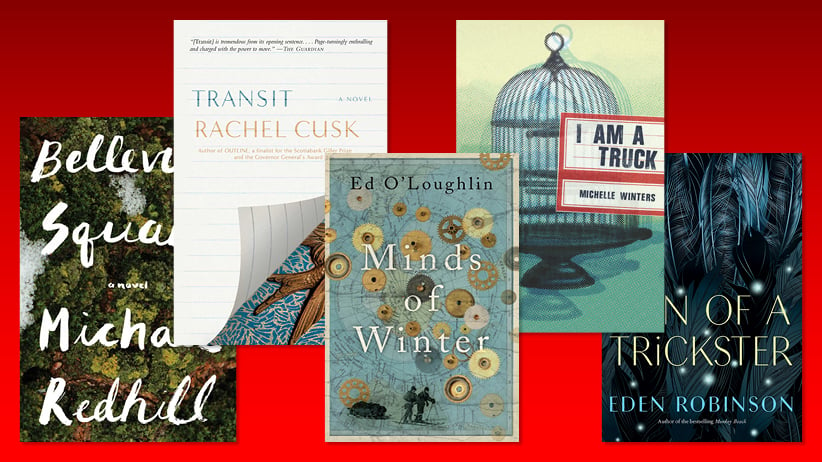

2017 Giller Prize–shortlisted books

Share

“It’s the jury, stupid,” remains the only solid guiding principle for anyone trying to parse a literary competition. Some years prize jurors are more in sync across the three major national awards than they are at other times. In 2016, only 11 writers filled the 16 shortlist slots available for the Scotiabank Giller Prize (which that year offered up, as it does from time to time, six finalists), the Rogers Writers’ Trust Prize and the Governor General’s Literary Award. In 2017, though, there is no overlap between last week’s WT nominees, and Giller shortlist released today, highlighting two juries—both entirely consisting of writers—drawn to intriguingly different literary ends. How far that each-jury-to-its-own tilt extends will be known on Oct. 4, when the GG jury unveils its finalists—no double nominees at all would be as unusual as last year’s five.

The 2017 Giller jury—Canadians Anita Rau Badami (chair), André Alexis and Lynn Coady, plus Richard Beard from Britain and American Nathan Englander—crafted an impressive, CanLit-spanning long list two weeks ago. The publishers were (in standard proportions) major multinationals or Canadian indies; the writers included minorities of all kinds (black, Indigenous, transgender); there were veteran authors and newcomers; they lived everywhere from Vancouver to Ireland. A broad church indeed, broad enough to cloak any literary preferences more nuanced than the jurors’ evident appetite for the darkly comic. Their shortlist is far more focused and revealing.

MORE: How CanLit was born

The finalists for the $100,000 prize, Canada’s most glamorous and richest—even the runners-up take home $10,000 each—are Rachel Cusk (Transit), Ed O’Loughlin (Minds of Winter), Michael Redhill (Bellevue Square), Eden Robinson (Son of a Trickster) and Michelle Winters (I am a Truck).

In contrast to the WT’s politically charged shortlist, the Giller’s leans towards veteran authors and literary-psychological pyrotechnics. Bellevue Square is praised in the jury citation for its “complex literary wonders, the doppelgangers and bifurcated brains and alternate selves.” Robinson’s novel gets a nod for grounding its protagonist’s life in “gritty, grinding reality,” but a shout-out for the way Jared’s “addled perceptions take us into a realm beyond his small town life, somewhere both seductive and dangerous.” Transit by Cusk, a Saskatoon-born British writer both celebrated and criticized for her seeming indifference to political issues and fixation on family life, is “an exquisitely poised meditation on life, time, and change.”

All three are well-established writers. Last year Robinson won the mid-career $25,000 Writers’ Trust Engel/Findley Award—a godsend, she said at the time, given her wonky furnace (and Canadian authors’ incomes). And, unlike anyone else on the long list, they have all made Giller shortlists before, with their debut novels in the cases of Robinson (Monkey Beach, 2000) and Redhill (Martin Sloane, 2001). Cusk was nominated only two years ago, for Outline, the first of a projected trilogy in which Transit is volume two. They are her eighth and ninth novels, and mark the career point when she acquired a separate Canadian publisher (HarperCollins) and Canadian editor (Iris Tupholme). It was Tupholme who unearthed the fact of Cusk’s Prairie birth (and Canadian prize eligibility), said the writer in 2015, and “badgered me into getting my birth certificate”—all of which raises the question of how many other nominations Cusk’s first seven novels could have brought her.

The newcomers on the list fit the veterans’ template and the jurors’ evident interests. Michelle Winters’ I am a Truck is a funny, rock-and-roll-filled story set in rural Acadia and filled with dialogue that ebbs and flows between French and English at a character’s whim. The Minds of Winter by Toronto-born Irish writer Ed O’Loughlin starts in the familiar CanLit territory of the Franklin expedition (which has attracted almost as much Canadian artistic interest as the Great War), but it soon spirals through time and geography. Like David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas, it’s a virtuoso piece of literary craftsmanship, and the jury loved that about it: “the mechanism of this novel is fascinating to observe.” Just like the workings of a literary jury’s collective mind.

MORE ABOUT BOOKS:

- Five must-read books for October

- Rogers Writers’ Trust shortlist shows off accelerating diversity of CanLit

- Q&A: NBC’s Katy Tur on her wild year covering Trump

- Why animals should be given the same legal rights as humans

- Salman Rushdie says Donald Trump is “demolishing reality”

- Helen Humphreys’ latest book is a hybrid of fiction and fact

- The five books everyone is talking about in September

- How CanLit was born