Strippers, Neil Young and Joni Mitchell

Our review of a new book by Graham Nash

Share

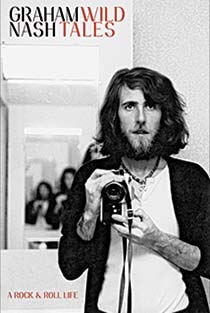

WILD TALES

WILD TALES

By Graham Nash

In his book Long Time Gone, David Crosby called Graham Nash “one of the best human beings alive” and “definitely the best harmony singer.” Nash’s own memoir paints him as the “glue” in Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, holding together the epically addled Crosby, the egomaniacal Stephen Stills and the downright weird Neil Young through some wild years indeed.

In a forthright, enthused and likeable voice, the singer and guitarist, aided by writer Bob Spitz, takes us from his days playing clubs in Sheffield, England, as a teenager (and sharing dressing rooms with strippers) through his mid-’60s success with the clean-cut, pint-swilling British Invasion quintet the Hollies to his long, strange trip with CSNY. Joni Mitchell, his girlfriend for two years, proves a pivotal figure in his move to California; she broadens his artistic horizons, and though he’s in awe of her, he’s too restless to settle down. Crosby, who opens his mind with pot, becomes an apt partner in crime.

Much of the book finds Nash playing Nick Carraway to Crosby’s party-throwing Gatsby at the height of record-industry decadence in the ’70s and ’80s. Nash is no angel himself, ingesting “enormous amounts” of cocaine, wooing his wife-to-be by getting her and her mother “insanely high” on hash oil, and attacking bandmate Stephen Stills on camera for the crime of being late to an interview. Nor is he particularly self-aware: he’s unbothered by his casual misogyny as a young, groupie-mobbed rocker and insensitive to the irony of making vampiric drug dealers rich while his band plays benefit shows for political and environmental causes. But his honesty is appealing, and where Young drifts in and out of people’s lives according to his own inscrutable agenda, Nash sticks around and has the often gripping tales to prove it.

He portrays CSNY as a hilariously dysfunctional enterprise whose members at various times vow never to work together again but are pulled back in because everything they touch turns to a gold record. Their success leads to excess and darkness, but in the end a degree of redemption; the one addiction that saves them is the music.

Mike Doherty

Visit the Maclean’s Bookmarked blog for news and reviews on all things literary