Thinking about The Bell Jar, while eating pasta for one

The 50th anniversary of the book–and Sylvia Plath’s death–inspires food for thought

Share

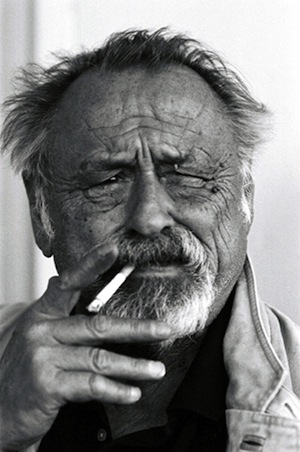

During that glorious lull between Christmas and New Year’s, I found myself alone one evening. I’d just finished reading The Raw and the Cooked, a collection of essays by Jim Harrison, an American author who’s written more than 30 works of poetry, fiction (including the novella Legends of the Fall) and nonfiction. He’s the sort of writer who gets as emotional over sitting down to a feast of game birds and a case of good Burgundy as he does about considering What It All Means. Actually, come to think of it, the meal and the thinking usually go hand in hand.

During that glorious lull between Christmas and New Year’s, I found myself alone one evening. I’d just finished reading The Raw and the Cooked, a collection of essays by Jim Harrison, an American author who’s written more than 30 works of poetry, fiction (including the novella Legends of the Fall) and nonfiction. He’s the sort of writer who gets as emotional over sitting down to a feast of game birds and a case of good Burgundy as he does about considering What It All Means. Actually, come to think of it, the meal and the thinking usually go hand in hand.

Partly inspired by Harrison’s solitary cooking adventures, I was eager to prepare dinner for one. I settled on a favourite pasta–one I imagined the author would admire in both portion and flavour: Cook half a box of Barilla spaghetti in a pot. Drain, after reserving a little starchy water. In the same pot, over low heat, melt a couple tablespoons of butter and add the juice of half a lemon. Add the spaghetti back in, along with some of the reserved water. Throw in a generous handful of freshly grated Parmigiano Reggiano, baby arugula and toss. Top your serving with freshly ground black pepper, Maldon salt and a drizzle of olive oil. (I had no woodcock stock, or duck confit, which Harrison would have most certainly added.)

With my bowl in my lap, and a glass of 2011 Casal Thaulero from Abruzzo, which, for the price of $8.25 has been referred to as the best pinot grigio in that price range available at the LCBO, I popped in a DVD I recently purchased for $3 from Value Village, Sylvia, the 2003 biopic of Sylvia Plath starring Gwyneth Paltrow. (I also purchased Working Girl. I was looking for Mr. Mom, but have never found it.) I’d forgotten Daniel Craig was cast as Plath’s fellow poet and husband, Ted Hughes–and was not disappointed to see the actor possessed 007-appropriate muscle tone three years before Casino Royale.

I can’t recall my initial reaction to the film when I saw it in a theatre 10 years ago. But I do remember that Anthony Lane of the New Yorker didn’t trash it entirely. Although he said the movie “plays slow and loose with the authenticities of Plath’s life, rearranging chunks of her existence as if moving furniture around a room,” Lane “admired it precisely because it refuses to play along with the mythologizing that has sprung up, and vulgarized, the lives of two poets.” So there’s that.

After I finished the film, the pasta and half of the bottle of wine, I got to thinking about a dinner party I attended in the summer (grilled steak, green onions and potatoes) where I admitted I wasn’t able to recall ever choosing a book based on the author’s gender. I wasn’t attracted to writers like Joan Didion, M.F.K Fisher, Jane Austen, or Harper Lee because they were women. Just as I hadn’t devoured Harrison–or Melville, Thoreau and Dickens–because they were men. I think I read out of the simple hope that they’ll be a character or a thought with whom or with what I might identify.

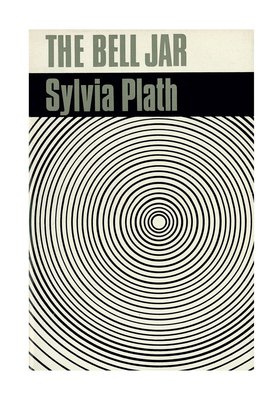

Remembering that conversation–and having just finished Sylvia–reminded me of when I read the The Bell Jar. Like many other things in life (cooking, wine, buying good quality shower curtains and bed sheets), I was a late bloomer when it came to reading books, particularly the sort that Mean Something. After a former roommate took note of a hardly uncommon obsession with J.D. Salinger in my early twenties, he told me I really ought to read The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath. It was like The Catcher in the Rye for girls, he promised. I was attracted more to the Catcher in the Rye portion of that statement than I was to the “for girls” bit. So I read it. And it did Mean Something. Probably the same things it meant to Winona Ryder’s character in Reality Bites, or Julia Stiles, in 10 Things I Hate About You or to anyone in The Gilmore Girls (the book is referenced in all three). Or maybe even something akin to Lena Dunham, who recently invited Twitter followers to tell her what The Bell Jar means to them, perhaps for inspiration to write this.

Remembering that conversation–and having just finished Sylvia–reminded me of when I read the The Bell Jar. Like many other things in life (cooking, wine, buying good quality shower curtains and bed sheets), I was a late bloomer when it came to reading books, particularly the sort that Mean Something. After a former roommate took note of a hardly uncommon obsession with J.D. Salinger in my early twenties, he told me I really ought to read The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath. It was like The Catcher in the Rye for girls, he promised. I was attracted more to the Catcher in the Rye portion of that statement than I was to the “for girls” bit. So I read it. And it did Mean Something. Probably the same things it meant to Winona Ryder’s character in Reality Bites, or Julia Stiles, in 10 Things I Hate About You or to anyone in The Gilmore Girls (the book is referenced in all three). Or maybe even something akin to Lena Dunham, who recently invited Twitter followers to tell her what The Bell Jar means to them, perhaps for inspiration to write this.

It never concerned me that Holden Caulfield probably meant more. Or that Franny Glass meant more than he did. Or, since we’re being honest here, that Zooey Glass meant more than the whole lot of them combined. (He was the one, after all, who said, “The goddamn sand runs out on you everytime you turn around. You’re lucky if you get time to squeeze in this goddamn phenomenal world.”) Regardless of both the protagonists and authors’ genders, they all influenced me.

Anyway, I thought about all of this, full on the couch, a little drunk, with the credits rolling and a fire roaring. I thought about how a big part of growing up, at least for me, was coming to the sometimes sad realization that my reactions to works of art are not unique. You want them to belong to you, and even imagine they were intended for your gaze alone. Maybe that’s what makes them works of art.

In the early morning of Feb. 11, 1967–50 years ago today–Sylvia Plath killed herself in her London flat nearly a month after The Bell Jar had been published. I won’t reread the book. I fear it wouldn’t resonate to my 38-year-old self, or worse, that it would remind me of all my twentysomething lost longings and hopes. But I sure hope others do.