The bountiful afterlife of Leonard Cohen

Cohen lives on with a new book, and a new album is even in the offing

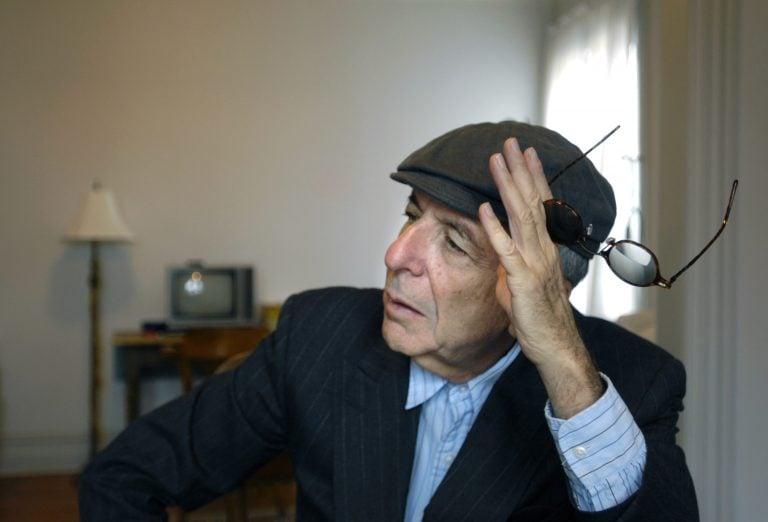

Leonard Cohen at home in Montreal IN 2007. (Charla Jones/CP)

Share

When I used to visit Leonard Cohen, at his house in Montreal and later in Los Angeles, I was always struck by the clear floors and bare walls. There were no bookshelves, and not a book in sight. You’d never guess you were in the home of a writer. At the time, I put it down to his regime as a Zen Buddhist monk who lived in the moment with no attachment to things. But he was incredibly fond of his big-screen Mac. One evening at his home in L.A., as he was searching for something on the desktop to show me, he scrolled through a folder containing hundreds of unpublished poems and song lyrics. When I asked him why he wasn’t doing something with them, he shrugged. After emerging from years of depression, for once he was content, and in no hurry to put himself out in the world again. This was in 2003, five years before Leonard learned he’d lost his fortune to an embezzling manager—a calamity that lit a fire under him, forcing him back onto the road in his late 70s to perform the most successful world tours of his career.

As it turns out, Leonard was not immune to hoarding. He just didn’t leave stuff lying around the house. But he had storage lockers filled with notebooks and papers. Now, two years after his death, some of that massive archive has surfaced in a new book, The Flame: Poems and Selections from Notebooks. Drawn from unpublished work spanning six decades, it includes 63 poems, song lyrics from his last four albums, excerpts from notebooks, the transcript of a speech he gave in Spain, emails, a text message sent hours before his death—and more than 100 of the poet’s self-portraits and drawings, along with reproductions of handwritten pages. Cohen helped select the poems and other writings, while leaving instructions for their organization with his editors, who completed the book after his death. The result is not a collection of finely polished work but a kaleidoscopic archive, a mix-tape of emotions that reveals Cohen’s fears and vulnerability with an unusually raw candour. After 10 books of poetry and two novels, it reminds us that the music man who taught the world to scale the chords of Hallelujah still considered writing his first and ultimate vocation.

In the last two years of his life, Cohen was afflicted by excruciating back pain from compression fractures of the spine, and by terminal leukemia. He knew he was dying, but it wasn’t the cancer that killed him, at least not directly. His death was caused by a fall in the night at his home in L.A. Having completed his final album, You Want It Darker, released just weeks before his death, he was immersed in his writing. “It was what he was staying alive to do, his sole breathing purpose at the end,” writes his son, Adam Cohen, in the book’s foreword. His father often told him he regretted not devoting more time to writing, he recalls, and quotes him saying, “Religion, teachers, women, drugs, the road, fame, money…nothing gets me high and offers relief from suffering like blackening pages.” Adam adds that his father “offered his literary consecration as an explanation for what he felt was poor fatherhood, failed relationships and inattention to his finances and health.”

Read more: Sharing memories of life and Leonard Cohen

Cohen, who once said, “Poetry is a verdict, not an occupation,” spent his dying months locked in the solitary confinement of the page, withdrawing from family and friends. His manager, Robert Kory—also the trustee of his estate—served as gatekeeper, fiercely guarding his privacy. In rescuing Cohen from financial ruin, he used the same strategy to engineer his comeback, insulating the singer from the pressures of touring with a strict no-visitors policy backstage. “In the last months of Leonard’s life,” says Kory on the phone from L.A., “he felt a great intensity, and was adamant about finishing this book. He saw nobody. Unfortunately, business continues, and we were launching an album.” So Cohen did the bare minimum to promote the record (and bid an unofficial farewell). He granted New Yorker editor David Remick a landmark interview; I was grateful for a pithy email exchange.

Leonard’s emails always had a playful zing. They were written with precise economy, with short line breaks like blank verse. His most recent piece of writing in The Flame is an email volley of rhyming repartee about God and darkness with poet Peter Scott, son of legendary Montreal poet F.R. Scott. It concludes with a text message that Cohen sent the afternoon before his death, a response to a photo of Peter with Sophia De Mornay-O’Neal, daughter of Cohen’s former partner, actress Rebecca De Mornay. It read simply: “Blessed are the peacemakers: for they shall be called the children of God.”

Twelve hours later, as Leonard lay dying after his fatal fall, he typed his last words in a string of emails to his close friend and Buddhist crony Eric Lerner, an American novelist and screenwriter (Bird on a Wire). Lerner recounts the exchange in a memoir published this month called Matters of Vital Interest: A Forty-Year Friendship with Leonard Cohen. The first email, arriving at 3 a.m., consisted of three lines from Dante’s Inferno in Italian, sent from the same Los Angeles duplex that the two friends had bought together in 1979. It was followed by a dire message. “In clear, grim prose,” Lerner writes, “he recounted how he’d gotten up to go the bathroom, and on the way back he fainted and took a hard fall, hitting his head on the floor.” At home in Boston, Lerner fired back a dark joke and waited. Finally, Leonard sent one last message, “describing how sweet it was to be back in his bed, telling me that the waves of sweetness felt overwhelming.”

Read more: Leonard Cohen’s third act

Although Cohen’s writings in The Flame span a lifetime, the book’s tone, and the selections he chose to publish, seem to reflect the almost giddy vertigo of an artist standing at the brink of death. They ricochet from bouts of cosmic desperation to jabs of dark and mischievous wit, revealing the Jewish comedian who always lurked behind the sombre mask of the Zen monk. Take “Kanye West Is Not Picasso,” his koan-like answer to a poetry slam:

Jay-Z is not the Dylan of anything

I am the Dylan of anything

I am the Kanye West of Kanye West . . .

I am the real Kanye West

Bob Dylan’s name arises at various points in The Flame. When he won the Nobel Prize for Literature only a month before Cohen died, as Leonard’s fans protested that their guy was more deserving, he said giving Dylan the Nobel was like giving Mt. Everest a prize for being the highest mountain, a sly evaluation that could be taken either way. In a round of self-deprecating stanzas from the notebooks, Bob pops up again as Cohen dismisses himself as “a minor figure in the junta:”

I still get many offers

but there’s someone I must thank

all of us were robbed

& Dylan was the Bank . . .

the leading man

the man I’ll never be

But like Dylan in his later years, Cohen seemed to take perverse pleasure in deflating his literary gravitas by flirting with nursery rhymes and doggerel. In one notebook excerpt, he unwinds the very mechanism of poetry.

Among my stories there is one

you’ve never heard before

though all I’ve said goes round it

like an apple round its core

It’s the poem as prayer wheel, spinning into infinity. During his years of retreat at the Buddhist boot camp on Mt. Baldy outside Los Angeles, Cohen would often get through the grind of pre-dawn meditation by running lines of poetry or lyrics over and over in his mind. And some of The Flame’s notebook entries unfold like an animated X-ray of his creative process. In an epic series of refrains that echo Hallelujah’s ardent song of the Bible’s King David, he keeps riffing variations on “David bent down/in the darkness of love…”— running at the poem with the patience of a man trying to rock his car out of a snowbank.

Perhaps no one had a more durable influence on Cohen than Roshi (Kyozan Joshu Sasaki), his cognac-loving, skirt-chasing Zen master on Mt. Baldy. A mordant poem in the book titled Roshi Said recounts a dialogue with him after Roshi was hit with a sex scandal at the age of 105: “Roshi said:/I give you lots of trouble…I should die/I said/It won’t help/Roshi didn’t laugh.” Lerner, another student of Roshi, writes that once the scandal broke, Cohen saw that his own reputation was being tainted as his name was highlighted in every news item. Understandably, he distanced himself from his master, but right up to Roshi’s death at 107, writes Lerner, “Leonard and Roshi were never closer.”

In the wake of the #MeToo movement, despite Leonard’s old-school image as a ladies’ man, he anointed even his briefest flings with enough kindness, respect and generosity to emerge unscathed, at least so far. Supplication, not aggression, was his style. As for his artistic legacy, it continues to expand after his death. McClelland & Stewart, his publisher since 1956, is re-issuing six early volumes of poetry that have been out of print for ages. And while The Flame is the last book that he had a hand in, there may be more to come. The scraps of Cohen’s notebooks in The Flame were plucked from more than 3,000 pages of transcripts spanning six decades. “I had no idea there was such a vast amount of material,” says Robert Kory, who’s had a team cataloguing the archive for the past year. It’s quite the trove, with items ranging from correspondence with his ex-lover Joni Mitchell to outtakes that include all 84 verses of Hallelujah.

Read more: ‘The heart will not retreat’: How we loved Leonard Cohen

Surprised to learn that his client had never used a literary agent, Kory recently engaged Andrew Wylie, who represents the likes of Salman Rushdie and Martin Amis, to push new Cohen publishing projects. And over the next few years, A Crack in Everything, the stunning multi-media Cohen tribute produced by the Montreal Museum of Contemporary Art, will tour the world, starting with New York, Copenhagen, Prague, San Francisco, and possibly Shanghai. There is even another Leonard Cohen album in the offing, with more recordings in the vault. Adam collaborated with him for the first time as a producer on You Want it Darker, and now he’s back in the studio, working with his father’s voice. In his foreword to The Flame, Adam quotes one of Leonard’s songs—I came so far for beauty, I left so much behind—then adds, “but not far enough, apparently: in his view he hadn’t left enough.” The song was written 40 years ago, in that abyss of middle-age when a poet begins to feel his creative life is over, and in The Flame he’s working down to the wire:

I’m trying to finish

My shabby career

With a little truth

In the now and here

—from If I Took a Pill

Leonard could be glib and immodest about his “career,” as if it were short-term obstacle in his path. As a poet with a biblical sense of time, he had always seemed at home in the future. And he tended to his legacy with assiduous care, framing “blackened pages” for posterity. I was tickled to come across these lines of a poem in The Flame: “All the walls in my house are bare/And I love the bare walls.” Now that we can begin to see what lies beyond them, it seems Leonard Cohen has left enough words and music for us to carry on without him.