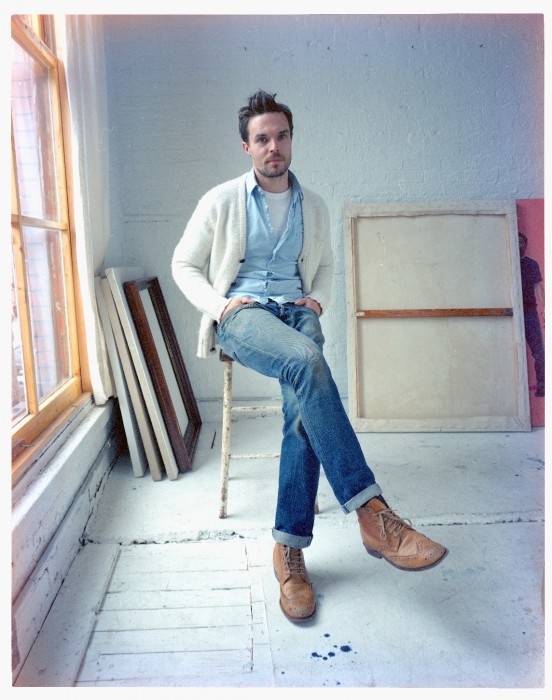

In Oliver Jeffers’s world, little kids befriend lost penguins and a bear with a penchant for flying paper airplanes confounds a town when their trees start to disappear. If that sounds like something out of a fairytale, you’re not too far off – the Irish-bred, Brooklyn-based author and illustrator has been the darling of the kids’ lit scene since introducing the world to his heartwarming, whimsical style of art and storytelling in 2004 with How to Catch a Star. Ten books and a long list of global awards later, Jeffers, who’s also a successful commercial illustrator and fine artist, continues to delight children – and the forever young-at-heart – with his sweet-but-smart approach.

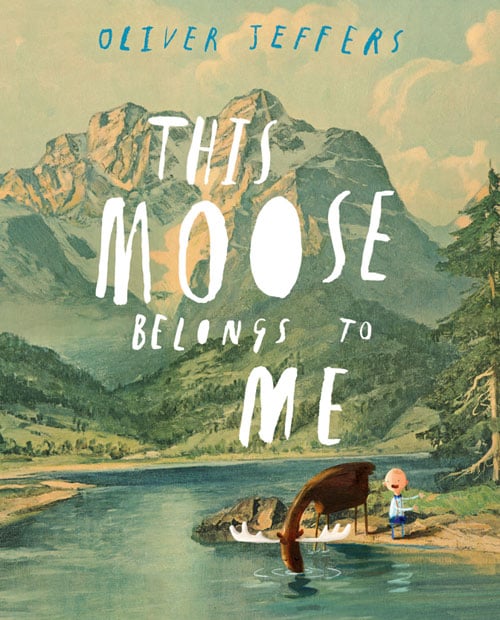

That widespread appeal has made Jeffers one very busy fellow just trying to keep up with the demand for his tall tales for the small set – hot on the heels of last year’s This Moose Belongs to Me and The Hueys in The New Jumper comes a second Hueys book, It Wasn’t Me, later this spring. Somehow in between bookmaking and art assignments, Jeffers also manages to get out of the studio and in front of his adoring audiences. He’s making a rare visit to Canada this week, meeting booksellers, signing books at a Chapters in Brampton, and appearing at Small Print Toronto’s fifth-anniversary Totsapalooza event (which sold out of its 500 tickets within days) before heading to Vancouver later this month for an appearance at the University of British Columbia.

The betoqued (but mittenless, having forgotten his gloves at home) and Irish-accented author took some time during his Toronto visit to speak with Maclean’s about kids, creativity and staying open to imagination.

Q: How did you first get started in the world of picture books?

A: Coming from Ireland, it really is a place of storytellers, and everybody has some story up their sleeve for any given occasion – people just going around in a circle telling stories one after another. So that’s always been a big part of my culture and upbringing. With regards to the art-making aspect of things, I went to art college considering myself as a fine artist and painter, and then switched over from the nebulous fine art program and went more towards design and typography and illustration, thinking I’d have a better chance of getting a job at the end of it. But I continued to make fine art, and a lot of the art I was making was mixing words and pictures together, using that as the basis for these short little narratives. And then one day when I was making a sketch for what was going to be a painting – it was what ended up becoming the book How to Catch a Star – it occurred to me that was an interesting concept. I thought, ‘I could explore this, maybe draw other ways that somebody might be able to catch something as intangible as a star.’ Once I had three or four of those, I realized, ‘This isn’t a series of paintings, this is actually a picture book that I’m creating.’ And once I made that switch in my brain, the rest of it came quite easily and naturally.

Q: You found a publisher (HarperCollins) quite quickly based on the strength of that first book – but given that it was a happy accident of sorts, did you have to consciously commit to working on more books?

A: Whenever I go over to HarperCollins, the editors ask me: ‘Is this a one-off, or do you have more planned?’ And I respond, ‘Oh, no, I have lots more,’ lying through my teeth. And then there was quite an awkward period – the first book I submitted in its entirety – it basically didn’t change. There were a few minor things, but essentially I made the book on my own unedited. After that, I had to learn to work with an editor – I had an idea of what I wanted to do, and they had an idea of what they wanted me to do, and it took two or three books for me to learn to listen to an editor, and for them to know that I was always right. (laughs)

Q: What sort of things inspire your stories?

Q: What sort of things inspire your stories?

A: My books aren’t exactly totally grounded within the rules of science, but a lot of the magic of my books is palatable and believable because they’re merely exaggerations of things that actually happen. So it’s not like there are dragons or time-travel or anything like that – but a boy can climb a rope to the moon and kids buy into that because a boy can climb a rope. That aspect of my work came quite naturally – I suppose I was just untapping the sort of books I wish I’d read when I was a kid, and the way in which I see my world anyway. It’s a lot of going with your gut instinct – when I’m formulating a story and extracting the ideas, I’ll start drawing, and sometimes the character just happens without me even thinking about them, and then I just go with it. I mean, Wilfred [in This Moose Belongs to Me], why does he have a bowtie and suspenders? It’s just the way I drew him. I realized that as soon as I stopped trying to make my style look like someone else’s and just listened to the way my hands liked to draw, and what was coming out of the end of my pencil when I wasn’t overly focused on it, that ended up being my style. So it was a very natural thing. And I learned to just go with that and not second-guess it.

Q: Do you feel that there is a certain approach to storytelling that works better for kids?

A: No. If there is, I don’t know. I’m quite open about saying that – I don’t really think about what kids want or take that into consideration when I’m coming up with stories. In fact, I don’t very often call them kids’ books – I call them picture books – because I don’t think they’re just for kids; they’re for anyone who wants to look at them. My target audience when I’m making them is me, frankly – I want to satisfy myself. It just so happens that my sense of humour and the way that I like to see the world seems to sit quite naturally alongside how three and four-year-olds approach things. (laughs) Kids’ books can seem forced or condescending whenever people try to think about what moral or lesson they’re trying to impart, whereas I don’t have any of that – I just try to be entertaining, and if a moral or a good value comes of it, then that’s an added bonus, rather than a point. There’s probably an honesty to the books that kids pick up on. I don’t really want to know – I’m afraid if I take it apart, I won’t be able to put it back together.

Q: There seems to be a move towards that more fluid sense of storytelling in kids’ books today, where both the artwork and the tales themselves are attracting readers of all ages.

A: I think we’re in an age where the best picture books that have ever been made are being made. There are so many wonderful people in the business – I think we’ll be spurring each other on. Possibly it’s a pushback against digital – there was a period where digital illustration was fashionable, but it didn’t last very long. The majority of picture books now are quite tactile and organic in the way in which they appear – whether they were made totally hands-on or whether they use software or not, I don’t know, but the actual outcome is anti-digital, in a way. And there’s something just comforting about paint on paper, and holding a book in your hands, that I don’t think is going to go away.

Q: You’ve had an amazing response from both kids and adults alike to your books – were you surprised by the reaction?

A: I try not to think about it. I’m only as good as my last project – I just want to keep moving forward. It’s brilliant that I get to do what I love for a living, and it’s incredible that people are along there for the ride. I do think I’m lucky.

Q: Any chance you’ll make the leap from picture books to a novel someday?

A: If I have an idea that would unfold better as a novel, then I might think about it, but I know enough good writers to know that I’m not really one. I know pretty much what’s happening through 2015, which is both a little scary, but there’s a safety in that. And frankly, if I can get through the list of things I have to accomplish by then, I’ll be doing pretty well, I think.