Review: The Dead of Winter

A homeless woman lies freezing near the entrance of a Montreal parking garage, warmed by crumpled-up newspapers and a Salvation Army sleeping bag. A man dressed in black like a priest approaches, offering a warm drink and a place to rest. She is never seen alive again.

Share

A homeless woman lies freezing near the entrance of a Montreal parking garage, warmed by crumpled-up newspapers and a Salvation Army sleeping bag. A man dressed in black like a priest approaches, offering a warm drink and a place to rest. She is never seen alive again.

A homeless woman lies freezing near the entrance of a Montreal parking garage, warmed by crumpled-up newspapers and a Salvation Army sleeping bag. A man dressed in black like a priest approaches, offering a warm drink and a place to rest. She is never seen alive again.

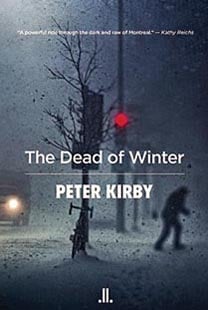

So begins The Dead of Winter, the first novel from Peter Kirby, an Irish-born Montreal lawyer. Shortlisted by Crime Writers of Canada for its Unhanged Arthur Award, celebrating the best unpublished first crime novel, Kirby’s book follows detective inspector Luc Vanier as he relentlessly pursues a serial killer targeting Montreal’s homeless. Everyone seems implicated in the investigation, from high-ranking clergy in Quebec’s Catholic Church and powerful business interests to the staff at a soup kitchen.

One of the pleasures of Kirby’s novel is the setting. In The Dead of Winter, Montreal is colourful and gritty. Thugs and lowlifes rub shoulders with the elite, while the city is pummelled by an endless succession of vicious snowstorms. Unsurprisingly, Kirby is especially adept at describing the inner workings of a law firm that may be involved in a corrupt land deal, and the tricks and loopholes Vanier uses to get his police work done—like convincing a judge to give him a search warrant in “world-record” speed.

Where Kirby’s novel falls a bit flat is in its character development, especially the women. We know Dr. Anjili Segal, the coroner, has an on-again, off-again relationship with Vanier, but we learn almost nothing else about her, save that “her surgical uniform couldn’t hide the curves of a woman in good shape.” Other females are equally opaque. From police officer Sylvie St. Jacques to Vanier’s teenaged daughter Élise to Mme. Collins, a mysterious figure implicated in the investigation, we never learn much of these women, or their motivations.

Vanier himself can border on cliché. He’s a hard-boiled, hard-drinking detective with a troubled past, who spends Christmas Eve alone listening to Patsy Cline in the dark over a glass of Jameson (until he’s pulled away to investigate a murder). This is a well-worn trope of the genre, but Kirby puts Vanier through his paces chasing a killer in a book that’s fast-paced and enjoyable.

Visit the Maclean’s Bookmarked blog for news and reviews on all things literary