The magnificent library at the heart of Anglo Quebec City

A surprising history of the Morrin Centre

Share

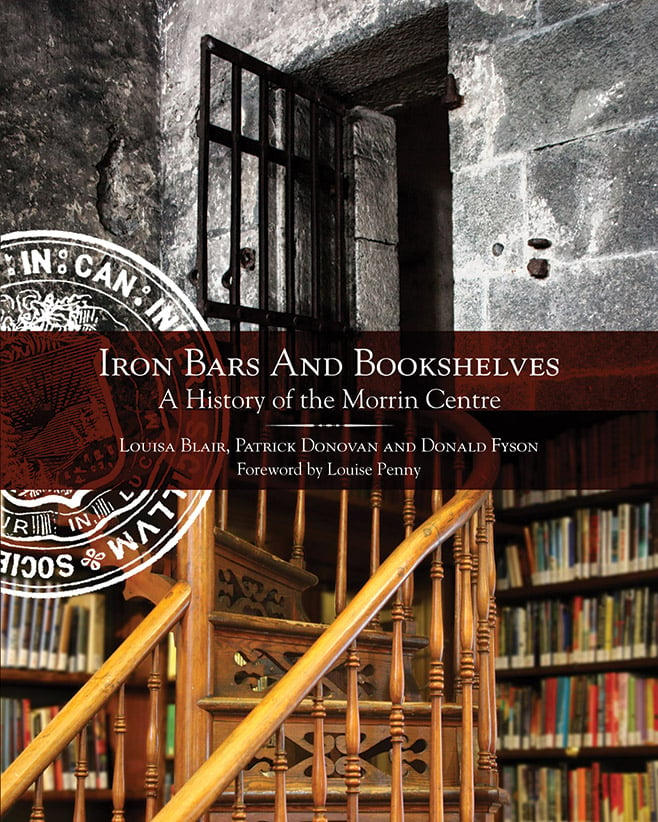

IRON BARS AND BOOKSHELVES

by Louisa Blair, Patrick Donovan and Donald Fyson

In its own haphazard way, the Morrin Centre, the subject of this loving and highly readable history, is as good a symbol as any institution in Canada of the often fraying but never quite broken ties that bind the nation. Over the past 200 years, the cultural heart of Anglo Quebec City has had its periods of eminence and prosperity, punctuated by longer bouts of poverty and anonymity, before its gorgeous library made an appearance in one of Louise Penny’s bestsellers about Chief Inspector Armand Gamache of the Sûreté du Québec. Now, freshly burnished and state-supported, it attracts a steady stream of tourists.

When the impressive neoclassical building that came to house the centre opened in 1812, it was a jail, with inmates ranging from murderers to debtors, including Philippe Aubert de Gaspé. A seigneur who had once served as city sheriff—the man in charge of the jail—Aubert de Gaspé ended up doing a three-year stint there, in a cell from which he could see his own house across the street. Decades later, he became a founding father of Québécois literature with his novel Les Anciens Canadiens.

By 1867, the prisoners were gone and the cells were renovated for the use of Morrin College, a Presbyterian island in Catholic Quebec, and the Literary and Historical Society of Quebec. Established in 1824 by Governor General Lord Dalhousie, who also founded his namesake university in Halifax, the LHSQ collected historical documents, hosted the likes of Charles Dickens for lectures, and played a key role in saving the Plains of Abraham from developers. It was also plagued by fires, evictions (before the college adopted it) and chronic underfunding, prompting the occasional mass sell-off of its treasures, just to keep the lights on. In 1966, the society shipped nine tons of books to Montreal for sale, including a 1632 edition of Champlain’s Voyages, which went to a Toronto collector for $4,000.

Penny’s Gamache thinks of the LHSQ and its library as the smallest of a set of Russian dolls: an Anglo society inside a French city, inside a French-English nation, inside an English continent. He could have found something yet smaller: the library’s wooden statue of Gen. James Wolfe. Its vicissitudes—commissioned by a city butcher who had served under Wolfe, and placed outside his shop; consistently knocked about by unhappy francophones; kidnapped and taken to England by Royal Navy cadets in 1838 (and later returned in a crate addressed to the mayor); the object of an arson attack while it was supposedly safe in the library (an Argentinian, angry over the British occupation of the Falklands, attacked it with two Molotov cocktails)—are a microcosm of the society’s own.