The many, harrowing lives of Carmen Aguirre

Mexican Hooker #1 is an intimate memoir from the Vancouver actor and writer

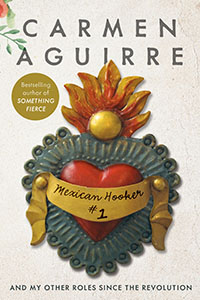

Mexican Hooker #1 by Carmen Aguirre. No Credit

Share

MEXICAN HOOKER #1

By Carmen Aguirre

An impulse shopper might select Carmen Aguirre’s memoir because of the colourful book jacket. With a Latin American echo of the “World’s #1 Mom” coffee mug, the kitschy fake souvenir on it suggests irony, maybe, or humour, sarcasm and wryness. The souvenir’s gold-painted banner hints at an eyeopening but zinger-filled journey as recalled by an accomplished artist—Aguirre is a writer, playwright and actor in Vancouver—through supposedly liberal but in fact racist and sexist industries.

“Don’t judge a book by its cover”—the impulse shopper would do well to remember that. Although flecked with light-hearted episodes, this memoir is most often profoundly intimate as it recounts harrowing, life-derailing traumas and hard-won survival.

Never less than mesmerizing, the on-the-move Aguirre describes a “radical feminist” upbringing in Chile, the “trials of exile” from her beloved homeland, her family’s early ’70s migration to California and later Vancouver (where she was viewed as “a poor brown girl”), a stint posing as “a super-privileged, apolitical Argentinian youth,” and a brief marriage while in the Chilean resistance—at age 11, she had returned to South America with her sister and mother, who joined the movement opposing the regime. Aguirre, who followed her mother’s lead, writes of living day to day “in fear of being arrested, tortured, and murdered for [her] underground activities.”

Early on, Aguirre evokes a triumphant day in 1990 when she was certain a “never-dealt-with” childhood rape had finally been cast from her body. Her certainty was premature. Across 13 chapters, the memoir returns to that horrific experience and its shattering aftermath. In April 1981, the “paper bag rapist” then terrorizing B.C. uttered this threat to 13-year old Aguirre in a Vancouver grove: “I have one bullet left. I’m going to chop up your cousin now in front of you, starting from the feet. Then you’ll help me put the pieces in a plastic bag. Then I’ll shoot you.” He didn’t, but he assaulted her brutally. Attending the parole hearings of her rapist, John Horace Oughton, decades later, Aguirre observes, “it would take a lifetime to understand the depth of the wound inflicted by his cruelty.” Exposed to words like these, a reader can only marvel at human resilience while also gasping at the forms of our depravity.