The murder of Joseph Smith

How the founding prophet of the Mormons went from charismatic leader to public enemy

Share

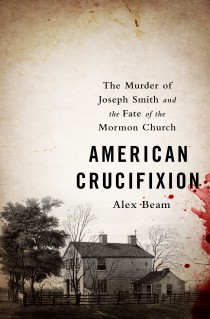

AMERICAN CRUCIFIXION: THE MURDER OF JOSEPH SMITH AND THE FATE OF THE MORMON CHURCH

AMERICAN CRUCIFIXION: THE MURDER OF JOSEPH SMITH AND THE FATE OF THE MORMON CHURCH

By Alex Beam

In his nuanced and engrossing tale of the first Mormons’ alternating periods of triumph and despair along the original American frontier—on both sides of Huck Finn’s antebellum Mississippi River—Beam illuminates not just their history but their nation’s. Under founding prophet Joseph Smith, the Mormons, like so many other Americans, were always on the move: Ohio, Missouri—from which they had to flee for their lives from other settlers, abandoning land and possessions—and Illinois. There Smith founded Nauvoo, a city built on a swamp, which his extraordinarily dedicated flock drained and made into the state’s most prosperous settlement, larger than Chicago.

The Nauvoo years, 1840-44, were a triumph for Smith. His city, its bloc vote courted by state politicians, grew continually from missionary work elsewhere in the U.S., Upper Canada and Britain. Smith himself was running for president, while divine revelation continued to descend upon him and he continued to convince his followers of the truth of what he proclaimed. Most of them, that is, for the Nauvoo years were also Smith’s downfall. The new doctrine of polygamy—its cultural shock obvious enough for Smith to keep all but one of his 30-plus marriages secret—was the crucial divisive issue that led to the prophet’s murder.

The church fissured with the revelation became known, creating an ominous opening for the simmering hostility of its neighbours: in June 1844 Smith and other Mormon leaders, menaced by ill-disciplined state militia, ended up in jail in the town of Carthage. An angry but organized mob stormed the building, killing Smith, 38, as well as his older brother, Hyrum. How it came to that, the transformation from charismatic leader to public enemy, from secure home to exile yet again, is the core of Beam’s story. Almost no one, Mormon or Gentile (as the saints referred to outsiders) comes out of it very well: not Joseph Smith, religious visionary and single-minded narcissist; not the feckless governor of Illinois, Thomas Ford; not Brigham Young, who made the fateful decision to abandon civilization (such as it was); and not the leaders of the anti-Mormons, far more galvanized by envy and resentment than scandalized religious fervour.

Which is not to say they weren’t consequential historical figures. Mormonism is America’s largest native religion, and the martyrdom of Joseph Smith is its key moment. It was his assassination that sent the Mormons to Utah and, eventually, into the mainstream of U.S. society.