The new Neanderthals

Acclaimed writer Claire Cameron’s title character is strong, sexy, smart and, yes, a redhead

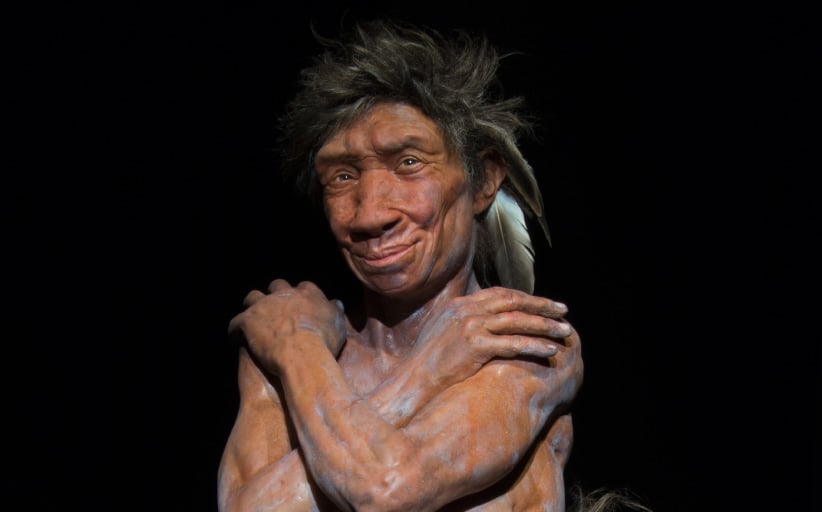

‘Nana & Flint’ are forensic reconstructions of the Gibraltar 1 (Forbes’ Quarry, 1848) and Gibraltar 2 (Devil’s Tower Shelter Cave, 1926) Neanderthal fossils by Dutch artists Kennis & Kennis. (S. Finlayson)

Share

Toronto novelist Claire Cameron, whose 2014 bestseller The Bear took place in the contemporary Canadian wilderness, moves across time and space to an equally dangerous locale for The Last Neanderthal, set in France 40,000 years ago. The intricate tale of Girl, the title character, and Rose, the modern-day archaeologist who discovers her bones, is a story of common humanity, including the fact that the more things change for pregnant women, the more they stay the same. The novel is also thoroughly immersed in the recent explosion in knowledge—and speculation—about our closest kin. Cameron spoke with Maclean’s about the lives and fate of the Neanderthals.

Q: You note that Neanderthal—“stooped over, hairy, primitive, dull”—is still an insult in use, but our cousins have been picking up a lot of good press lately. Why are we so fascinated?

A: Since 2010, yes, and the first draft of the genome. That really changed the perception. They’re almost like a Shakespearean foil now. We can see ourselves in them.

Q: And we did see them, literally. That makes a difference.

A: It’s the interbreeding between the two groups that really takes it up a notch: between one and four per cent of European and Asian DNA is Neanderthal.

Q: So, as usual, it’s all about us. What did we get out of this genome infusion? Red hair, which Girl has, has caught the popular imagination.

A: We are a self-centred storytelling species, aren’t we? Yes, there’s the red hair, though that comes from a small sample. Scientists are starting to look into things like immunity. For genes to stick around, they do need to play some sort of role often—not always—but there are all sorts of things in the news at the moment about what and why.

Q: Red hair, herpes and bad skin, I’ve seen.

A: Yes, quite negative, but also protection against schizophrenia.

Q: They were clearly as caring, as witnessed by their burials, and much more flexible and adaptive than we once thought.

A: Neanderthals were tremendously successful for 200,000 years, through all kinds of climate change—longer than us, so far. There’s a recent study about the plaque on their teeth, and one group in Spain had a vegetarian diet. Amazing. The point is that Neanderthals weren’t one thing. They were people spread all over Europe and Asia in all kinds of environments and they were as varied in their responses as we are.

Q: The other side of “all about us” is the idea of modern humans as the doom of the Neanderthals, either by deliberate violence or simply by showing up and ruining their world. What is the thinking on that now?

A: I’m by no means an expert, but I did go through all the new research. I think that their extinction is tied to low population—humans moving into their territory was one more pressure on their food sources. Disease, genetics, all those things that exert pressure on large predators pushed them [to a tipping point]. There were a lot of extinctions of larger mammals around their time. We no longer have giant sloths or cave bears.

Q: With large animals, extinction doesn’t actually require killing them all. They’re so slow in their reproduction. If that is disrupted . . .

A: Exactly, yes. All you need is fewer reproducing and the balance can tip. Neanderthal sites were quite far apart and their family groups quite small, so the balance is precarious.

Q: It can’t be coincidental that we were on the scene at the time of their demise, though, because we certainly weren’t ignoring them. The kind of permanent effect on our genome must have meant massive, ongoing gene flow—as sex is politely called—between us.

A: The genome sequencing came from two bones from two places. You only find as much DNA as there is in your sources. So I don’t think we have a full picture yet of what was going on, but there may have been more interbreeding than originally thought; it’s one of those older assumptions that I think is changing. Our ability to think in tens of thousands of years is limited, too. That’s certainly one thing I learned about myself writing this book. Human migration is as messy as humans are. The fairly simple out-of-Africa story is getting complicated—the DNA shows we co-evolved alongside Neanderthals, rather than after them.

Q: Close contact doesn’t mean always peaceful.

A: I had a big discussion with Yuval Noah Harari, who wrote Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind, after he read a draft of my novel. He said, “You know, conflict with humans doesn’t come into this.” I thought a lot about that, and I’m sure there was conflict between Neanderthals and humans. I’m sure there were also friendships and relationships as well. That’s my speculation: it’s going to very much depend on who is under threat and who is under pressure and the circumstances under which you meet and then the individual personalities involved.