The Oliver Sacks we didn’t know

Anecdotes and revelations about the late Sacks’ personal life converge into a deeply personal meditation on love

No credit

Share

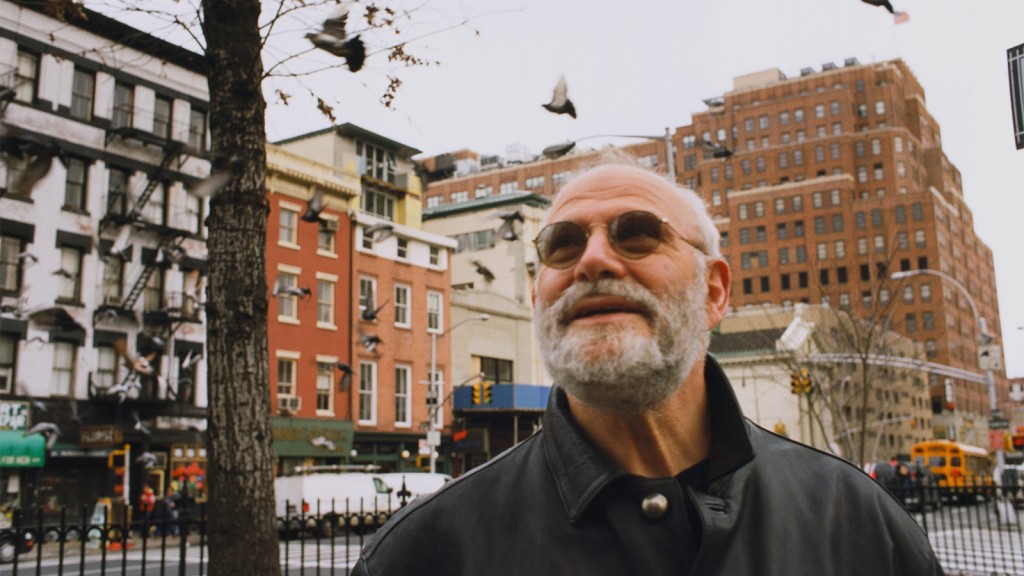

August 30, 2015: Oliver Sacks passed away in New York at the age of 82. Below, a review of his last book.

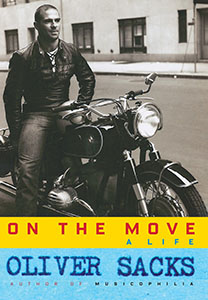

ON THE MOVE

By Oliver Sacks

In a dozen books published over nearly 15 years, Oliver Sacks has plumbed the most difficult of mysteries about the human brain. From men who mistake their wives for hats to women woken up from Parkinsonian stupor with L-Dopa to anomalies of all five senses, Sacks has relayed case after case with a distinct mix of metaphor, clinical insight, and wells of empathy. On the Move, his newest book, is his most overt attempt at memoir, in which earlier anecdotes and revelations about his personal life converge into a deeply personal meditation about what—and whom—he’s loved throughout his life.

We learn of Sacks’s early love and care of motorbikes, which take him all across the United States in the 1960s, freshly emigrated from England. Sacks takes the reader to Los Angeles’ Muscle Beach, where weightlifting contests give this young neurologist, perpetually afflicted with crippling shyness, a community and sense of purpose that would be undone by excessive drug use (later conquered). He retells earlier stories of clinical cases and of places he’s lived (most notably City Island, a tiny hamlet across from the Bronx) with fresh vigour. And for the first time, Sacks describes his romantic life, wells of feelings for men never fully reciprocated, decades of celibacy, and then, more recently, a late-in-life love that cause Sacks to feel “an intense sense of love, death, and transience, inseparably mixed.”

For all that Sacks’s previous books have addressed his fallible physical state—shattered legs, broken hips, cataracts, deafness, and a bout of cancer among the maladies—On the Move feels like his most blunt address of mortality. Part of this must be deliberate, seeing as Sacks is at his most overtly emotional and personal, but some of it is a quirk of timing; the book has an added layer of poignancy thanks to his New York Times op-ed reveal of terminal cancer earlier this year.

As a result it was impossible, for me, to read On the Move without wondering whether this might be Sacks’s last written address to the public. If so, it’s a stellar coda to a spectacular, singular career in letters. But for goodness sake, let’s hope it’s not. Let’s hope Oliver Sacks keeps moving, with the familiar restlessness of mind and spirit, to the next series of topics that fascinates him, and by extension, us.