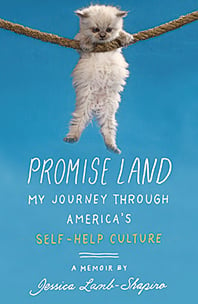

The Trouble with Self-Help

A review of an author’s journey through self-help culture

Share

Just when it seems that earnest, self-actualizing, self-help “journeys” have reached a morbid saturation point comes a sharply observed, nicely nuanced, laugh-out-loud funny memoir that blows the genre out of the water. Appropriately, Lamb-Shapiro is herself a product of the self-help movement, as the daughter of a child psychologist who tried, with limited success, to strike it rich with such products as “feeling” playing cards and a “suicide-prevention app.” As a child, she accompanied her father to exhibition halls filled with self-help merchants; as an adult, she went with him to The Dr. Oz Show when he appeared as the crisis-du-jour “expert.”

By then, Lamb-Shapiro had begun to see a self-help paradox in her own life: Her father’s profession provided no solace after her mother committed suicide when she was a baby. Her desire to come to terms with her mother’s death, an event swept under the rug, as well as her struggle with her own neuroses, animates the narrative.

It’s one that takes readers through a cook’s tour of contemporary self-help: walking on coals, making a “vision board,” enrolling in behavioural therapy to cure terror of flying, grief camp for children and a dating seminar conducted by the authors of The Rules books, now The Rules empire. As Lamb-Shapiro writes: “Successful self-help empires create their own economies, which could be described either as trickle-down or Ponzi schemes.”

It’s a gimmicky, time-worn format, to be sure. But the author’s mordant wit and self-awareness make it feel fresh. She ably distills self-help history dating to Stoic philosophers into fascinating, germane nuggets, as she nimbly balances the intelligence of C.S. Lewis with B.F. Skinner’s flaky “baby box.” The self-help gospel is all-American, she writes, an approach that dovetails nicely with culturally valued traits of independence and self-reliance. But her memoir (also a poignant love letter to her father) makes clear that self-help is not a solo activity: “The best thing about self-help is that it frees you from needing other people,” Lamb-Shapiro writes: “The worst thing about self-help is exactly the same.” Thus, the final takeaway presents a bigger paradox than the one she started with: the knowledge that the self can never fully help itself all by itself.

Anne Kingston

Visit the Maclean’s Bookmarked blog for news and reviews on all things literary.