The troubled life of Canadian outlaw Daniel Wolfe

Joe Friesen tells the story of the founder of Indian Posse, Canada’s largest street gang

Share

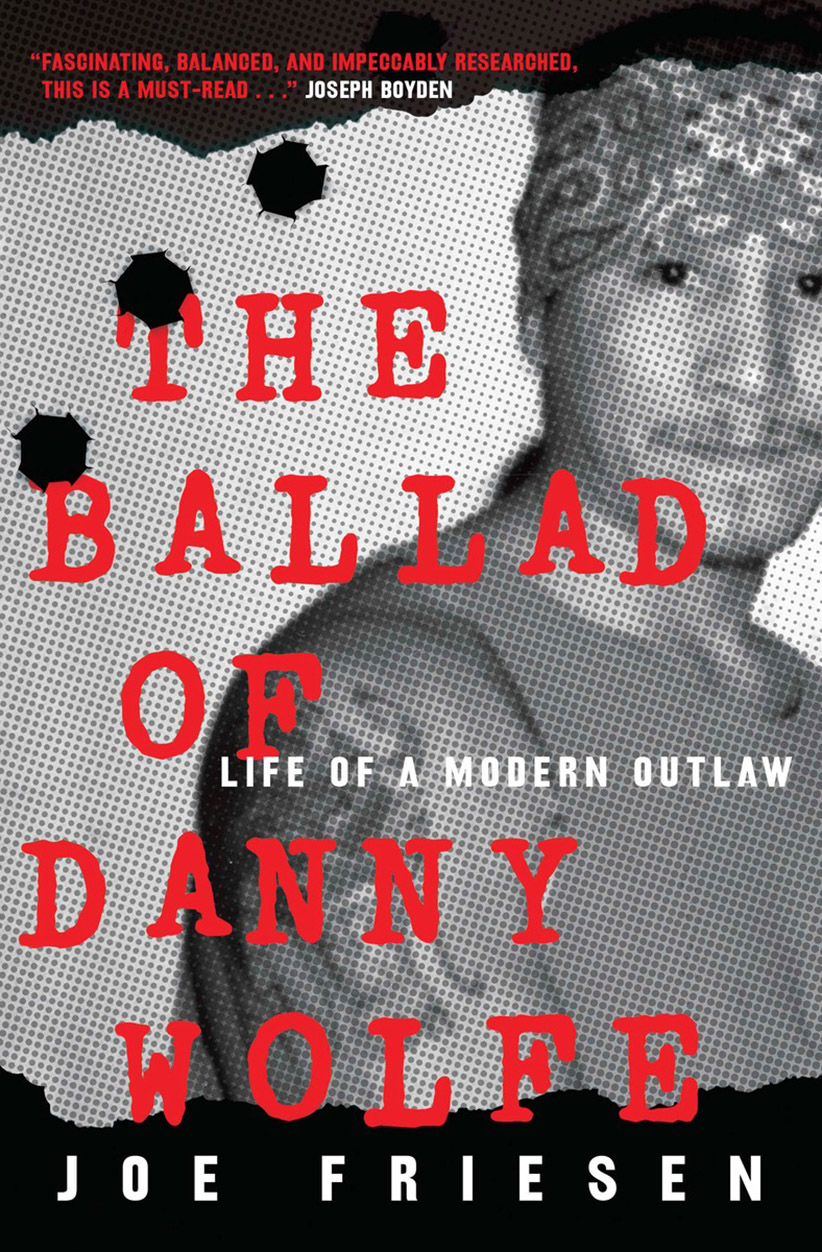

THE BALLAD OF DANNY WOLFE

By Joe Friesen

Daniel Wolfe, D-Boy, among Winnipeg’s most notorious gangland figures, went out in the end with a whimper, an unlikely fall for the founder of Indian Posse, Canada’s largest street gang. A prison shank meant to intimidate him somehow sliced through a carotid artery. What looked like a nick belied massive internal damage. As Wolfe calmly sipped from a coffee, he collapsed. He was dead at 33.

He’d been recently returned to federal custody after leading one of the most spectacular prison breaks in Canadian history, having somehow managed, in the fall of 2008, to dig a hole through a wall of the crumbling Regina Correctional Centre. Five others followed Wolfe out—most of them high-ranking gangsters facing murder charges, including Wolfe and his brother. That was in fact Wolfe’s third prison escape; while still a boy he’d vaulted a prison fence using a pole from a ceremonial teepee.

His persona was no less fantastical. To some, he was a revolutionary, a Robin Hood figure who dreamed of giving kids messed up by unstable parents a home, structure, a way to make money and feed themselves. But Wolfe, a wiry 120 lb., who wore his black hair down his back, was also a sociopath and a cold-blooded killer who unleashed a flood of drugs and violence across the Prairies, enslaving those same kids into a brutal life with no good ending. Globe and Mail reporter Joe Friesen, a Winnipegger by birth, weaves together this story in an essential new book, which grew from a feature for the paper, retracing the birth and rise of Indigenous prairie gangs.

Danny and his brother Richard, older by one year, it turns out, are a pretty good starting point. By six and seven, the Wolfe boys, the products of three generations of residential school survivors, were stealing food and blankets, sleeping in stairwells to escape the violence and alcoholism of their home. At 12 and 13, they joined forces with five North End Winnipeg buddies to create their own “family,” a gang they named the Indian Posse.

Using warrior imagery, the IP positioned itself as a kind of rebellion against the state. The attitude, the slogans like “Red ’til dead,” the smudging: all were like catnip to Indigenous kids raised with zero sense of their own identity, struggling with foster care, abuse, racism. They were the ones Danny preyed on, the kids wandering the North End after dark with nowhere to go.

Long after his death, thousands continue to be similarly entrapped. In this way, the legacy of Danny Wolfe, part scourge, part saviour—if only in his own mind—will live on for generations.