The unseen history of ‘white trash’

Nancy Isenberg examines the long history of class in America

Share

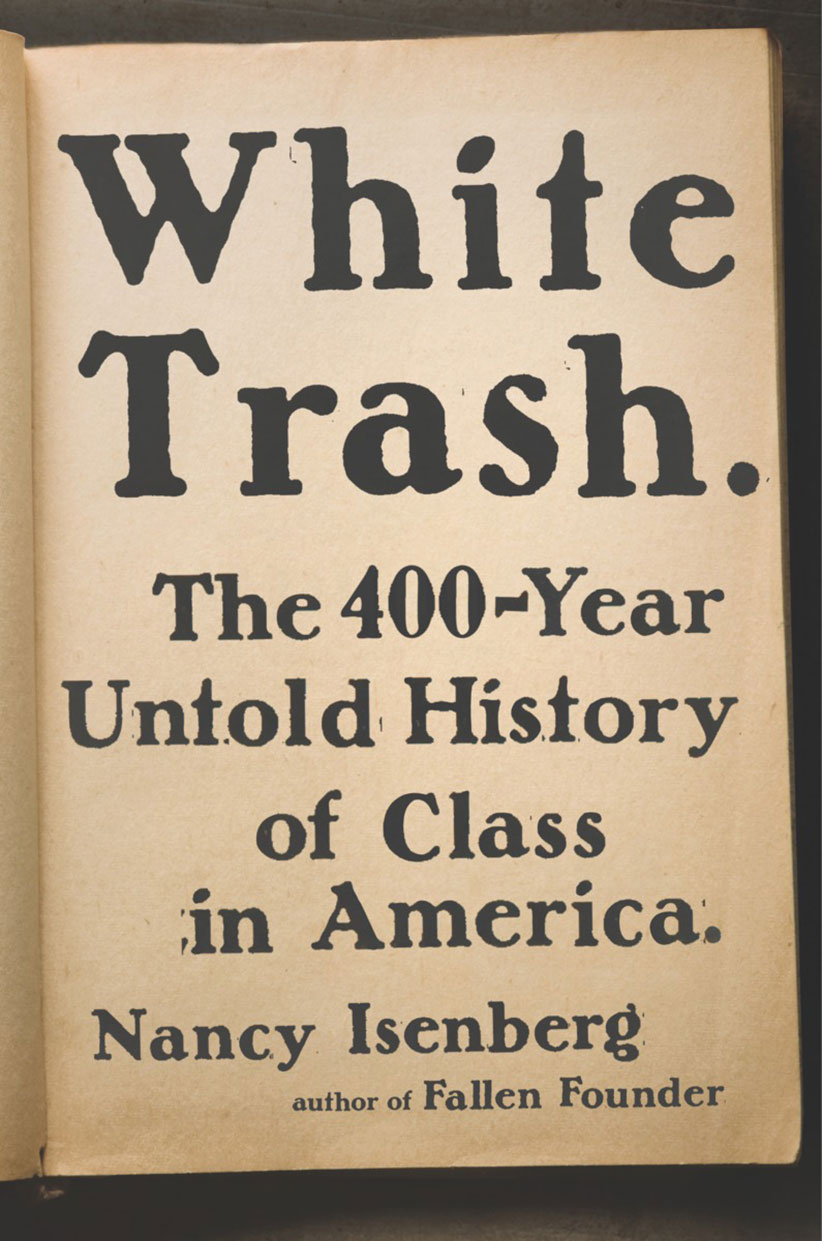

WHITE TRASH

By Nancy Isenberg

One of the central factors in American history has always been one of the least mentioned: class. Even in purely economic terms, early colonial settlement was bedevilled by the question of labour: where to get the workforce to perform the brutal task of turning North America into a replica of Europe, and how to bend the workers to the task. Racial slavery was the obvious and eventual answer for commercial agriculture, but from the beginning, those in England promoting colonial schemes universally presented them as win-win projects—not only would investors reap the wealth, they would rid the realm of its human garbage.

Richard Hakluyt the elder (1530-1591), one of Elizabethan England’s chief colonial enthusiasts, referred to those he thought transportable overseas in indentured servitude as the “offals of our people.” Such commonplace imagery resonated for decades as much as any dream of avarice. In 1619, King James I wrote the Virginia Company asking for its help, not in filling his coffers, but in clearing his palace environs of vagrant boys.

By the early years of the new republic, America’s landless white poor, the direct descendants of those who had crossed the Atlantic with nothing, were squatting all over the eastern side of the Mississippi, engaged in intermittently violent clashes with land speculators and the wealthy men who possessed legal title to most of the best land. They had already acquired most of their disparaging nicknames—cracker, clay-eater, swamp people and, by 1821, white trash—and, as unoccupied land disappeared and a commercial society bloomed, a similar caricature of their appearance as well. They were thin, toothless and “tallow”-complexioned—a negative marker in a colour-obsessed culture—all outward signs of interior degeneracy. They became deeply entrenched as the class into which those perched a few rungs above feared falling, while they themselves clung desperately to the rung they held: just above black Americans. As President Lyndon Johnson put it in 1964, “If you can convince the lowest white man that he’s better than the best coloured man, he won’t notice you’re picking his pocket.”

Isenberg handles all this with verve and a dose of acid, a historian simply fed up with Americans ignoring their own history. When she deals with recent times, she notes the dual-track right-wing attitude to the white poor, a vote-mining celebration of redneck chic (from love of Duck Dynasty to elevating Sarah Palin to vice-presidential candidate) combined with continuing social censure. Now that white trash has evolved from emaciated to obese, conservative writer Charlotte Hays commented, perhaps they should recall how pioneers at Jamestown realized that hard work might be accompanied by “a little starvation.” (If Hays had been referring to “the real Jamestown,” responds an acerbic Isenberg, she might have written “A lot of starvation and a little cannibalism.”) The left, for its part, has little but scorn to offer people who make up a significant proportion of Donald Trump supporters. The unseen politics of class, Isenberg concludes, are inextricably entangled with the politics of race in America.