Walking as a spectator sport

A review of ‘Pedestrianism: When Watching People Walk was America’s Favorite Spectator Sport’ by Matthew Algeo

Share

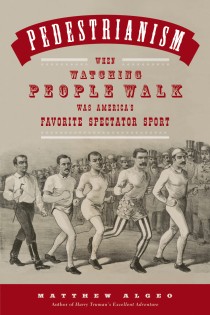

PEDESTRIANISM: WHEN WATCHING PEOPLE WALK WAS AMERICA’S FAVORITE SPECTATOR SPORT

PEDESTRIANISM: WHEN WATCHING PEOPLE WALK WAS AMERICA’S FAVORITE SPECTATOR SPORT

By Matthew Algeo

The subtitle of this entertaining book will surprise a lot of modern sports fans, especially baseball aficionados. Even after the first pro leagues came into existence, in the 1870s and ’80s the spectacle that Americans crammed into stadiums to see was men walking. And walking: six-day competitions (never, of course, on the Sabbath) in which champions routinely circled a dirt track for more than 700 km. The sport set a template that has never vanished from American life. Intensive press coverage acted as both cause and effect, creating celebrity athletes who earned fortunes in prizes and endorsements. Talent was the overriding factor, so opportunities opened for immigrants and black walkers (star competitor Frank Hart was regularly referred to as “the negro wonder” in the newspapers), and even for women. There was massive gambling and thus, as night follows day, gambling scandals. Almost as frequent were the doping scandals (coca leaves) and riots, equally inevitable when hard-drinking fans gather in crowds, fortunately less so.

Algeo traces the sport’s roots to a bet. Two New England pals wagered on the outcome of the 1860 presidential election: the loser would have to walk from the State Building in Boston to the site of Abraham Lincoln’s inaugural address in Washington, 765 km, in 10 days, arriving as the new president began to speak. Loser Edward Weston missed his deadline by five hours, but he attracted considerable celebrity—because of the wagering—along the way; he even got to meet Lincoln who, holding no grudge for Weston betting against him, offered to pay the walker’s train fare home.

After the Civil War, Weston began putting on exhibitions, taking in thousands of dollars for the pleasure of watching him circle the track for days (although he sometimes played the cornet too while he walked). Soon Weston had rivals for his champion’s purses, and the mania was on. What killed it in the end was a newly mechanized society’s newfound need for speed. Bicycle racing, then cars and airplanes: the world before the Great War, as ours still does, preferred pace to endurance.

BRIAN BETHUNE