REVIEW: Vivian Maier: Street Photographer

Edited by John Maloof, foreword by Geoff Dyer

Share

Photographs so swiftly attract our inner muse. Confronted by their mystery we fill in the blanks, devising the most satisfying narratives, imbuing the blankest of faces with the knowingest of smiles. Few faces, though, are as blank or as knowing as Maier’s, a nanny whose first book of photographs has arrived posthumously, decades after they were taken.

Photographs so swiftly attract our inner muse. Confronted by their mystery we fill in the blanks, devising the most satisfying narratives, imbuing the blankest of faces with the knowingest of smiles. Few faces, though, are as blank or as knowing as Maier’s, a nanny whose first book of photographs has arrived posthumously, decades after they were taken.

It’s a treasure of over 100 black and white images, shot mainly in the ’50s and ’60s in New York and Chicago, a paean to vernacular life. A boy carries a blur of pigeons. Kids in an alley take a scolding from a burly white-haired man. Some convey the directness of an icon: a black man rides a massive draft horse bareback, with rope reins, through the city. There are dead horses in the gutters and panhandling men in well-kept suits. Buttoned-up cops cart off bloodied drunks. The long shots contain the warmth of Bruegel: in the corner of a schoolyard, a priest in a cassock drills a ball at an adolescent boy.

Little is known of Maier—as Dyer, a novelist, observes, she “exists entirely in terms of what she saw.” She grew up in France, moved to New York in 1951, then turned to nannying in Chicago. When free, she roamed the streets shooting, showing the results to no one. It’s said she was briefly homeless in old age, but children she’d cared for learned of it and intervened. She died in 2009, at 83. No one knew of her work, which surfaced only in 2007, when Maloof, a Chicago entrepreneur, bought a bundle of her negatives, sight unseen, at an auction held after she failed to pay for a storage locker. (The book’s failure is that it lacks much of this backstory.)

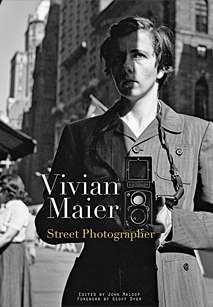

Who was she? In self-portraits she holds her Rolleiflex like a talisman against her chest—a boyish face with a frank, blank expression. In the final print, captured unawares in a mirror fleetingly held aloft in a workman’s gloved hands, she’s suddenly smiling in her truest account of herself.