Why it would be nice to be Amish: Book review

Whatever liberating, near-spiritual benefits that writing provides Russell, his words also seem to take on his worries.

Share

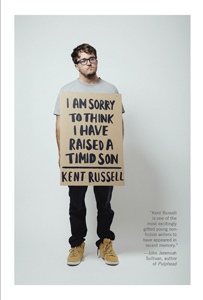

I Am Sorry to Think I Have Raised a Timid Son

Kent Russell

Russell descends from a line of writers—most perceptibly, David Foster Wallace—for whom reporting is an act of self-discovery. His impressive debut collection of essays is filled with people in pursuit of extreme experiences, of idyllic freedom and authentic lives. The book’s primary searcher, though, is Russell himself. In the people he writes about who actively seek out danger—such as a self-immunizer who attempts to withstand five snake bites in two days—Russell sees a risk-taking he wishes he could exhibit; those who inhabit isolated, often mocked communities—such as the Amish in Lancaster County, Penn., whom Russell visits in order to write about their knack for baseball—seem at least to have achieved a comfort in their own skins that he covets.

Russell is drawn to subjects who have unselfconsciously embraced their obsessions, who care little about mainstream society’s judgments, and he characterizes writing as his own source of escapism, as “a means of fleeing yourself and plunging trance-like after transcendence.” Yet whatever liberating, near-spiritual benefits that writing provides Russell, his words also seem to take on his worries. As his sentences latch onto you, they infect you with their anxieties. The latter, in fact, come to feel like the work’s life force; that they come through so forcefully in these essays indicates the unnerving but always compelling power of Russell’s prose.

The main anxiety that runs through Russell’s essays is symbolized by Daniel Boone, the 18th-century American frontiersman who provides I Am Sorry with its title and hangs over Russell as “the avatar of that particular American—practical and not theoretical, active and not contemplative.” I Am Sorry is a theoretical and contemplative struggle with that ideal, one that, particularly in the book’s best essay—an account of Russell’s two-week visit to his parents’ home that’s split up and interspersed, diary-style, throughout the book—is exemplified by Russell’s relationship with his strong-willed, cantankerous father. The strain between the two men exemplifies the book’s central conflict, which pits Russell against a notion of masculinity—self-reliant, unemotional—that he was raised to replicate but abhors, one that leaves him fighting bouts of anger and depression but that, no matter how far he travels and how much he writes, he can’t shake.