William Shakespeare: A man out of time

How Shakespeare’s plays—400 years later—have remained the best explorations of our own political and cultural fights

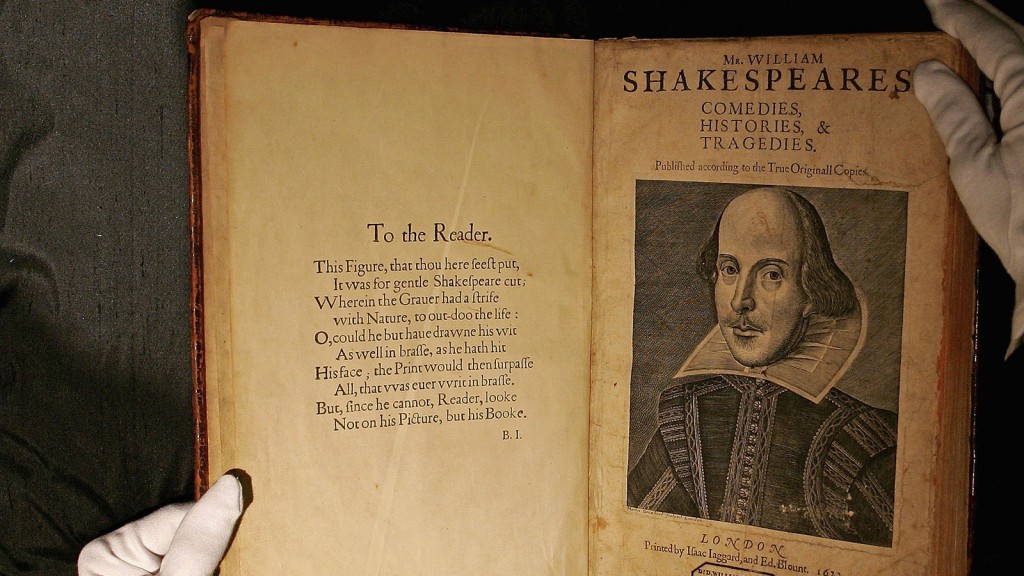

A Sotheby’s employee handles a copy of William Shakespeare, The First Folio 1623 on July 7, 2006 in London, England. The most important book in English Literature, the First Folio edition of Shakespeare’s plays (1623), will be offered in Sotheby’s sale of English Literature & History on July 13th, and is estimated to fetch GBP 2.5-3.5 million. (Scott Barbour/Getty Images)

Share

Age cannot wither him, nor custom stale his infinite variety. Gender reversal aside, what William Shakespeare wrote about Cleopatra is no less true about him. For someone 400 years dead this month, the Bard is not only very much alive, but as quicksilver as ever. And in this, the spring of his quatercentenary—when Shakespearean productions, studies and commemorations are rising to a crescendo—traditional and formal takes are sharing the stage with endless reimaginings, including gender-blurring versions and radically revamped history plays.

Shakespeare’s marvellous malleability is entwined with his familiarity, especially in the Anglosphere, where he is sunk deep in our DNA. As a source of quotable wisdom and beauty, his plays—referred to by devotees as “secular scripture”—are rivalled only by the sacred Scripture of the King James Bible, and they seem to every generation to speak directly to its concerns. That’s because, Stratford Festival actor Graham Abbey says, the plays—whether about English kings, Trojan heroes or Italian lovers—are at bottom “domestic dramas.” They are about “fathers and sons, mothers, sisters, daughters—roles we all play.”

#MyShakespeare: Twelve Canadians deliver their favourite lines from the Bard

Watch actor Colm Feore below, and see more here, with new videos rolled out every day until the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death on April 23

Shakespeare’s genius intuited and made intensely personal the deep social changes of his time, says James Shapiro, the Columbia University Shakespeare specialist and author of Contested Will and The Year of Lear, “He wrote at the dawn of modernity, in a time of increasing xenophobia and prejudice. Above all he wrote as households were changing to families. All this stuff is still front-page now because we haven’t worked it out yet, including the family part. I’d love to live in a world where Shakespeare didn’t matter, but I don’t.”

As Baltimore’s Cohesion Theatre Company staged its Hamlet in March, the governor of North Carolina signed into law perhaps the most notorious piece of anti-LGBT legislation in the U.S. There was no direct connection between that and Caitlin Carbone playing the Prince of Denmark as a woman—a lesbian one at that—but the political echoes were present throughout the two-week run.

“What Hamlet goes through are human things, as easily expressed by a woman as a man,” says Carbone. “But one of our missions is to tell stories in the voices of people who don’t normally get to tell their stories, and we often cast in an unconventional way in to achieve this.” That Cohesion can do this with a 415-year-old play, in a way scarcely possible with anything more modern, “absolutely speaks to the universality of Shakespeare’s characters and the malleability of his plays,” Carbone adds. Mind you, the actress—dressed in high grunge style, her hair dyed blond, and declaiming before a silhouette of the Seattle skyline—was also channelling Kurt Cobain: “infinite variety,” indeed.

In Stratford, Ont., Canada’s pre-eminent Shakespearean festival offers a quatercentenary season of Macbeth and two productions which, each in its own manner, push hot buttons: Breath of Kings, Abbey’s two-part adaptation of Shakespeare’s history plays, and As You Like It. In the comedy, Seana McKenna, whose distinguished career has seen her tackle two dozen of the Bard’s major female roles, will play Jaques. But not as an actress in a masculine role, as McKenna did in 2011 with King Richard III. This time, Jaques is a woman.

Gender-blurring has been trending that way for some time. Stratford actress Sarah Afful has done both—last season the black actress was Kate’s sister (the ironically named Bianca) in The Taming of the Shrew and has played an unnamed soldier (complete with fake beard) in the past. “I can’t pretend I am colourless,” says Afful, who takes on Lady Macduff this year. “All I have to bring to the table is who I am. When I went out on stage last year with my white sister, my antennas were up as I was wondering how people were accepting it. It takes a beat—perhaps they’re thinking, ‘Maybe she was adopted’—but the audience adjusts, the play goes forward.”

Actually transforming a character into a woman is a giant step further. As McKenna points out, there’s scarcely a work more pregnant with possibilities for that than As You Like It, where gender fluidity is already baked into the text. “The main female character spends much of the play pretending to be a man. Given that Shakespeare’s actors were all male, you had, four centuries ago, a boy playing a woman playing a man.” Jaques’s signature speech, “The seven ages of man,” one of the Bard’s most beloved passages, can sound fondly nostalgic from an actor; in a woman’s voice, such lines as “a soldier / Full of strange oaths… / Seeking the bubble reputation / Even in the cannon’s mouth,” will be “thought-provoking for an audience,” says McKenna.

If gender—whether it is fluid or fixed (by birth or choice)—is much on our minds now, so too is our era of violent political upheaval. Such times always bring renewed attention to the Bard’s history plays, which are “about the arrival of modern political leadership and the hollowness of victory” says Stratford artistic director Antoni Cimolino. Since 9/11, the histories—the eight plays that cover the dynastic struggle between the house of York and Lancaster between the deposition of Richard II in 1399 and the death of Richard III in 1485—have become the Shakespearean works that speak most urgently to the 21st century. Radically reimagined productions, combining and truncating different segments of the larger cycle, have been mounted around the world.

The Wars of the Roses, a landmark 1963 adaptation of the four plays that cover the Civil War proper, has been revived several times this century, most recently in 2015 by Trevor Nunn, former artistic director of the Royal Shakespeare Company. It fuses the more exciting bits of the three Henry VI plays into an extended introduction to Richard III. The critically lauded Dutch work Kings of War adds Henry V to that quartet and boils the lot down to a 4½-hour staging. Opening at the Barbican in London on April 22, Kings—which veers between nut-and-bolts portrayals of modern war and scenes of a dynasty carving up spheres of influence over afternoon tea—uses video and contemporary settings to raise echoes of everything from the Godfather movies to Osama bin Laden and George W. Bush. (Shakespeare’s secular scripture is trumping its contemporary sacred Scripture—it’s telling that no one conducts Easter liturgies in the Barbican, but Henry V is taking over Salisbury Cathedral, the site of a recent production from the Antic Disposition Company.)

The opening act of our contemporary political era was the creative genesis for Abbey’s Breath of Kings, which spans an earlier cycle of plays (Richard II, Henry IV and Henry V), and features, in the role of Prince Hal, Araya Mengesha—the first actor of colour to walk Stratford’s stage as an English king. Abbey recalls waking up in northern New York state on the morning of 9/11 and racing for the border, driving into Canada only seven minutes before the crossing was shut. “Then we were in Stratford thinking of our upcoming performance of Henry IV in light of this. You know how it opens, ‘So shaken as we are, so wan with care’? The audience was full of Americans that night, trapped in Canada by the border closure, and Abbey met a tearful middle-aged man who still hadn’t managed to contact his family. “He told me all he could think to do was turn off CNN and go listen to Shakespeare.”

As much as the discontent of our times, Breath will need to channel the story of the man cut off from his family, for the production to resonate as Abbey wishes: “You should leave the theatre thinking how the play applies to your life, or it hasn’t done its job.”

Shakespeare has always done his job, Shapiro thinks, because of his clear-eyed focus on family. That’s why he matters to audiences far beyond elite playgoers. “Lately, I’ve been to see the Royal Shakespeare Company in Brooklyn with David Tennant as Richard II—oh, the fight for my other ticket!—but also Romeo and Juliet in a women’s prison upstate,” says Shapiro, who can get into any production he wants. “Two hundred women—no jewellery because it’s not allowed but all made up because they were at the theatre—all rapt, all moved to tears, especially by the retribution scenes, by Romeo killing Tybalt. As far as I am concerned, those actors are doing God’s work.”

Broken families and last hopes for second chances, Shapiro adds, are what lie behind the burgeoning popularity of Shakespeare’s late romances, in a world full of aging Baby Boomers. Cimolino agrees. “A father finding his daughter, a statue coming back to life,” he says of The Winter’s Tale, a currently ascending work. “Shakespeare, like the rest of us, knows that’s magic, not real world.” It’s not, as the playwright makes plain, an entitled reward for following the rules or a prize that can be snatched by those who do not. Shakespeare questions everything, including rules, values and risks, and because of that we can play him as we will.