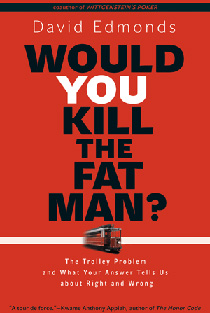

Would You Kill The Fat Man? The Trolley Problem And What Your Answer Tells Us About Right And Wrong

Would You Kill The Fat Man? The Trolley Problem And What Your Answer Tells Us About Right And Wrong

By David Edmonds

Trolleyology is a jokey name for a serious business, which is why Edmonds, a senior research associate at Oxford University’s Uehiro Centre for Practical Ethics, can be so lighthearted in his tone when he examines how people reason—and feel—their way through complex ethical dilemmas. As first designed by philosopher Philippa Foot in postwar Britain, the trolley problem sets up a scenario in which a runaway tram is barrelling along toward several people (usually four) tied to the tracks. To save them you, the observer and only possible agent of change, must sacrifice a single fat individual.

Originally, the size of the fat man carried no moral freight of its own, but was simply a matter of equivalent weight. If one life was to save several, then the victim had to have the same trolley-stopping mass as four other lives. (This also has the effect of removing from the problem the altruistic solution of a standard-sized observer sacrificing his own life.) Now, however, increasingly negative attitudes toward obesity are starting to affect people’s instinctive reactions to the scenarios.

Responses tend to fall into two broad streams. There is a powerful appeal in the utilitarian logic of the greatest good for the greatest number, logic that doesn’t bode well for the fat man. But more of us incline to the idea that it is unethical to use any fellow human as the means to an end, a reaction that keeps the fat man alive.

Of course, with philosophers involved, the issue is nowhere near that simple. Over the decades the deep thinkers have steadily added twists to Foot’s scenario. One of the first and most eye-opening of the additions was to increase the amount of agency required. Originally, the bystander had the opportunity to pull a switch, diverting the tram from the track with the four men to a spur line. Problem solved—except for the fat man obliviously strolling along the spur. But what if the fat man, still oblivious, was on a bridge spanning the track when you came along and realized that toppling him onto the track was the only way to save the four?

It turns out that instinctively—we don’t actually reason this out—far more of us recoil from the logical solution in the second scenario than in the first. It makes no odds to the fat man, who is dead in either case, but humans seem hard-wired to draw a distinction between a foreseeable side effect that sadly results from doing good (switching the tracks) and purposefully harming another, no matter how noble the cause (pushing the fat man off the bridge). Edmonds’s exploration of why this is so is at the heart of his thoroughly delightful book.

Brian Bethune

Visit the Maclean’s Bookmarked blog for news and reviews on all things literary