A new book showcases vintage photos of Canada’s most iconic restaurants

From the beavertail to the California roll, immigrants have shaped what we eat for centuries

Share

Food trends shift faster than you can say “pasta chips,” but Newfoundland-based food writer and restaurant critic Gabby Peyton pins them down in her new book, Where We Ate: A Field Guide to Canada’s Restaurants, Past and Present. It’s the culmination of Peyton’s year-long exploration of the annals of Canadian food history, concentrating on the legacy of major culinary landmarks. The result is a chronological compendium of the country’s restaurant culture, peppered with recipes and historical photographs that stretch from pre-Confederation inns to contemporary Indigenous-owned restaurants.

Between 2020 and 2021, Peyton interviewed nearly 85 food historians, chefs, restaurant owners and food writers, and dug through archival directories, newspapers and menus. She traced Canada’s restaurant culture through the Auberge Saint Gabriel, a 1754 Montreal inn and the first restaurant in North America to get a liquor licence; the first Tim Horton’s Donuts, which opened in Hamilton; and Bill Wong’s, the progenitor of the Chinese buffet. Peyton also ended up visiting 25 of these restaurants, like the 111-year-old United Bakers Dairy in Toronto, most known for its golden cheese blintzes. Everywhere she went, she found iterations of the same story.

READ: Canada’s Best Places to Eat Now

“Canadian restaurant cuisine is the amalgamation of centuries of immigration, barring Indigenous cuisine, which didn’t really exist in restaurants until the 2010s,” Peyton says. Ginger beef, ubiquitous in small-town Chinese restaurants, was created by Chinese immigrants in Calgary to satisfy beef-loving prairie dwellers, and donair sauce is a version of tzatziki that a Greek immigrant in Halifax concocted to make the garlicky condiment more palatable to locals. Peyton calls this trend “adaptation food”—dishes made by immigrants who tweaked their cultural cuisine to suit local tastes and ingredient availability.

Until recently, that was the story of Canada’s culinary canon. But there has been a shift: Indigenous chefs are now showcasing traditional recipes, and some cutting-edge restaurants have moved away from adaptation food. “More Canadians are travelling abroad, seeing different cuisines on social media and gaining access to a myriad of ingredients in local grocery stores. This has created a growing appetite for international cuisine,” Peyton says.

READ: A lot has changed at restaurants since the pandemic—starting with how much it costs to eat out

Where We Ate is not just about what we ate in the past. The book traces Canada’s culinary evolution and the immigrant stories that continue to propel it. “The work here is by no means an encyclopedia nor a complete history of our country’s restaurants,” Peyton writes in the introduction. “It’s a love letter.”

Locals know summer is around the corner when the Arbor in Port Dover, Ontario, opens for the season. Founded in 1912, the beloved staple serves up burgers, hot dogs, dipped ice cream, and Golden Glow—the sweet, freshly squeezed orange drink that put the restaurant on the map. No one but the proprietors of the Arbor know the recipe, and current owners Pam and Andrew Schneider have ensured it remains a closely guarded secret.

In the 1920s, “Meet me under the clock at Johnson’s” was an Edmonton catchphrase. Greek immigrant Constantinos Yeanitchous—who changed his name to Con Johnson, citing pronunciation issues—opened Johnson’s Cafe inside the Hotel Selkirk in 1920. Although a fire destroyed his business in 1961, there’s a replica (with an updated menu) at Fort Edmonton Park. Greek immigrants like Yeanitchous made crucial contributions to Canadian restaurant culture. They not only invented the donair and Hawaiian pizza, but helmed restaurants of all stripes from Saskatoon to Halifax, especially in the ’60s and ’70s. Hospitality was one of the few industries available to newcomers, and for many, it became the family business.

Cheeseless Roma Bakery & Deli pizzas are a birthday, funeral and wedding mainstay in Hamilton, Ontario. Founder Philip DiFilippo Sr.—whose parents immigrated from Abruzzo, Italy, in 1910—tried this type of pizza in Rome for the first time and came back hoping to reproduce it. But when he first opened Roma in 1952, he didn’t sell much Italian food because there was still post-war anti-Italian animosity. That changed after the introduction of Canada’s 1971 multiculturalism policy, which nationally recognized the importance of cultural diversity and helped Italian food take off. Today, the restaurant is owned by the third generation of DiFilippos. Peyton was able to try its iconic pizza when one of her interview subjects shipped her a slice; she says the light, fluffy dough and tomato sauce absolutely live up to the hype.

Opened in 1954 on the sixth floor of Winnipeg’s downtown Hudson’s Bay Company store, Paddlewheel was one of Canada’s first cafeteria-style department store restaurants. “This is one of the restaurants I most wish I had been able to visit while it existed,” says Peyton. “Everyone I interviewed spoke about it with such affection.” Diners would serve themselves hamburgers, roast turkey, Jell-O and more on veneered lunch trays branded with “The Bay” logos. Over the restaurant’s 59-year-old lifespan—it closed in 2013—much of the decor went unchanged.

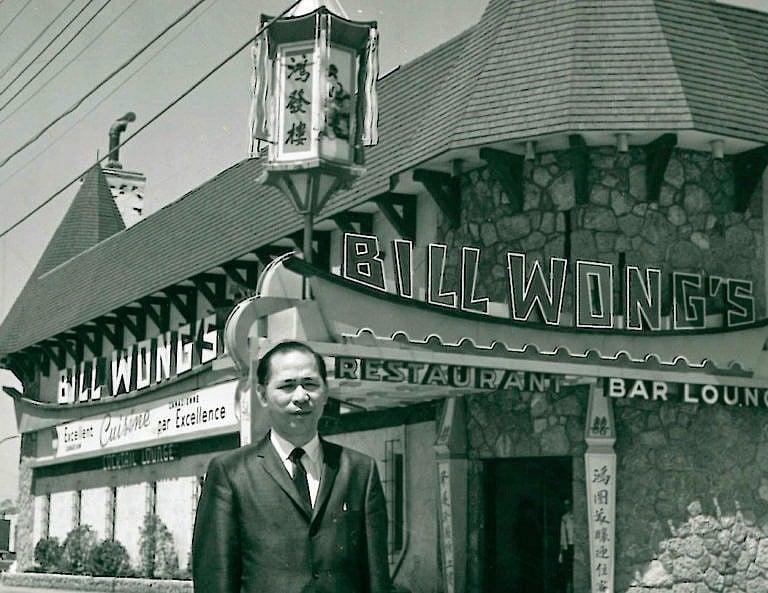

In this photo, Bill Wong, the creator of Chinese buffet in Canada, stands in front of his eponymous Montreal restaurant, which he opened in 1963. Born in Montreal to Chinese immigrant parents, his first restaurant was House of Wong, Montreal’s first Chinese restaurant outside of Chinatown. Bill Wong’s, his second restaurant, sat 1,000 people and offered an innovative buffet-style service with a mix of Canadian and Chinese dishes. The journalist Jan Wong, Bill’s daughter, told Peyton that he was inspired by a roast buffet at a family member’s wedding. Since Chinese food is often served family-style, he thought it would translate well. Judging by the fact that nearly every Canadian town now has a Chinese buffet of its own, he was right.

Tim Horton’s Donuts—the official ancestor of today’s ubiquitous (and no longer majority Canadian-owned) coffee house—opened in Hamilton, Ontario, in May of 1964. The chain dropped the apostrophe in 1993 to satisfy Quebec’s language laws (apostrophes don’t signal possession in French). Hockey player Tim Horton originally wanted to open a fried chicken and burger joint. His business partner, Jim Charade, helped refocus the idea on doughnuts and coffee. He saw an opportunity with the rise of car culture, which promoted a demand for easily transportable food and drinks.

The iconic beavertail—whole wheat dough pulled flat, fried and coated in cinnamon sugar—is a twist on German flatbread. Co-creators Grant and Pam Hooker, an American-born couple who moved to Canada in the 1960s, tweaked Grant’s grandmother’s recipe when his daughter observed that the traditional flatbread looked like a beaver tail. This photo shows their second BeaverTails stall, which opened in 1981 on Ottawa’s frozen Rideau Canal. (The first launched in ByWard Market a year before.)

The so-called California roll was actually invented in Vancouver by Japanese chef Hidekazu Tojo, pictured here at Tojo’s, which opened in 1988 and which he still runs today. In an era when raw fish raised the eyebrows of customers and local health inspectors, Tojo designed the roll to warm people up to sushi. He hid the seaweed under a layer of rice and stuffed in avocado, egg omelette and local crab, a readily available meat that was familiar to locals and served fully cooked—a crucial factor that helped him circumvent the public’s aversion to raw seafood.