Catharsis consumerism at the 9/11 memorial museum

The social satire writes itself, our columnist suggests

NEW YORK, UNITED STATES, SEPTEMBER 8: A general view of the National September 11 Museum on September 8, 2013 in New York, NY. Following the 9/11 attacks in New York, the former location of the Twin Towers has been turned into the National September 11 Memorial & Museum. (Photo by Cem Ozdel/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images

Share

Immediately after 9/11, then-president George W. Bush told Americans to get on with their lives—to travel, to spend, to keep the economy going—lest the terrorists win. So there’s some weird synchronicity in the fact that the National September 11 Memorial & Museum, which opens to the public today, has become an exemplar of an emerging trend best described as “catharsis consumerism,” wherein every experience, no matter how profound, sacred, distressing or uplifting, requires some take-away or enjoyment. The 9/11 museum, a site commemorating the most horrific event to take place on American soil—one that resulted in the loss of thousands of lives and that now houses unidentified human remains—has come under attack itself for boasting a gift shop selling FDNY dog vests, silk scarves adorned with images of the the fallen twin towers, and Pandora charms. In “Little Shop of Horrors,” the New York Post quotes Diane Horning, whose son died at the World Trade Center, expressing her anger that the place feels like a cheap roadside attraction: “To me, it’s the crassest, most insensitive thing to have a commercial enterprise at the place where my son died.”

Horning is also unhappy that a restaurant will open on the site, the details of which became public yesterday. Danny Meyer, who operates the Union Square Café and is one of New York’s most successful restaurateurs, will operate the 80-seat Pavillion Café slated to open this summer. In a release, Meyer describes his latest venture in a burial site in sombre terms as “a place to rest, to reflect and, hopefully, to be restored.” All is carefully cloaked in tastefulness and patriotism. Visitors will be offered a “subdued, seasonal, mostly vegetarian menu” with soul-nurturing “comfort foods like tomato soup, grilled cheese and brownies.” Appetizers (ricotta with peas, salmon confit, red-lentil hummus) will be “designed to be shared.” The focus is on made-in-the-USA: “ingredients from local farms” and “New York-made draft beers and American wines.”

The social satire writes itself. It’s also a modern truism that you can’t run a cultural institution without providing consumer take-away—hence, gift shops selling Frank Lloyd Wright-inspired dish towels and Klimt-inspired earrings, along with first-rate restaurants. Meyer’s Modern, located in New York’s Museum of Modern Art, is always packed. Anyone who visited the touring According to What? Ai Weiwei show last year will have faced the ironic spectre of viewing antique Chinese vases painted as political insurrection in the exhibit, which were then reproduced and repackaged as trendy home decor for purchase on the way out. Context, as they say, is everything.

It’s received wisdom that gift shops and restaurants pay the bills and keep the operation open, as the 9/11 Memorial pointed out in a statement: “To care for the Memorial and Museum, our organization relies on private fundraising, gracious donations and revenue from ticketing and carefully selected keepsake items for retail.” Critics of the museum, which has been mired in controversy from Day 1, counter that the gift shop is required to offset a poorly run operation with inflated executive salaries.

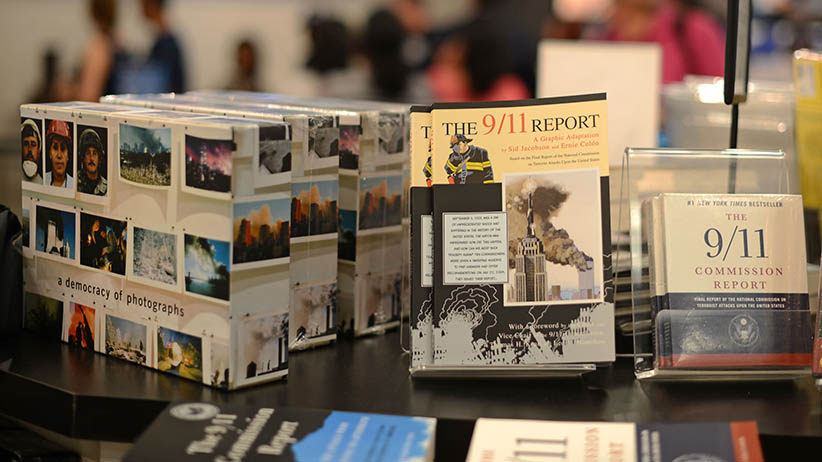

It’s no surprise there’s been backlash to the backlash to the the 9/11 gift shop by some people marshalling the, “Hey, everybody else does it” argument beloved by seven-year-olds. And it’s true that museums commemorating grief or war or historical tragedy—the USS Arizona Memorial at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii, Oklahoma City National Memorial & Museum—have souvenir stops. You can buy posters and postcards at Anne Frank’s house, and books at Auschwitz-Birkenau. It isn’t difficult to mount a Mobius-strip argument that catharsis consumerism nurtures connectivity in a consumer culture. But it’s one thing to buy a history book at Auschewitz, another to pick up a pair of “blossom earrings” at the 9/11 museum. The first instructs, the second is intended to make you feel good. And that’s the crux of the uproar: the irreconcilable disconnect between the comfort and pleasure being experienced by visitors to the latest NYC tourist attraction and the reason why they are there, a rupture no amount of buying crap memorabilia will ever begin to heal.