Cooler crullers

The richer, better heeled cousin of the common doughnut is suddenly everywhere

Share

Even for a chef who’s worked with Charlie Trotter and Anton Mosimann, cooking at the James Beard House is a bit like scoring a ticket to the Oscars. So when Jason Parsons, executive chef of the Peller Estates Winery Restaurant in Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ont., was invited to the venerable New York City institution earlier this year, he was chuffed. His multi-course extravaganza included such delicacies as poached lobster linguine, and venison infused with cocoa nib, basil and merlot. But he wanted a note of fun, he says, and a gesture that was quintessentially Canadian. So for appetizers, he decided on a punnish take on a classic: that gloriously fatty ring of fried dough known as the doughnut.

Parsons’ version was really a Timbit of sorts: a complex, savoury morsel stuffed with an ice-wine chicken-liver parfait and rolled in crisp feuilletine flakes, sea salt and sage—in other words, related only very distantly, by marriage, several times removed, to that humble treat handed out with double-doubles across this country. “As a chef, you look at things everyone else takes for granted,” Parsons said. “And so doughnuts—it’s that idea of saying, this could so be better.”

He’s not alone in remaking an old standby. The richer, better heeled cousin of the common doughnut is suddenly everywhere. The Doughnut Plant, an industrial-meets-old-timey shoebox of a store on New York City’s Lower East Side, offers beautiful handmade ones in ever changing flavours—orange, rose petal, peanut butter (in a jam doughnut, naturally). Its crème brûlée, feted by Maxim, is a favourite of Mark Isreal, the shop’s owner (and pioneer, by far, of the haute-doughnut trend—he opened years before the craze hit, and has 27 stores in Japan and Korea). At San Francisco’s Dynamo Donuts, you can try caramel de sel or maple-glazed bacon apple. The celebrated Petite Thuet, Marc Thuet’s bakery in Toronto, sells decadent chocolate and plain beignets (hole-less doughnuts) rolled in sugar, and the Corner Café at the Drake Hotel has ones filled with coconut cream, their bestselling flavour, or, in spring, bright pink rhubarb jam, says pastry chef David Chow.

Following the trail blazed by the cupcake, the doughnut is making an appearance on restaurant menus, too. Order it at Corinna Mozo’s Delux Restaurant in Toronto, and a half-dozen warm buttermilk doughnut holes arrive at the table in a white paper bag marked “DONUTS.” Flavoured with cinnamon and nutmeg, they’re delightfully crisp on the outside, moist and light on the inside—like a hush puppy in texture; Mozo gilds the lily by serving them with a little ramekin of Chantilly cream. The Hoof Café, that temple to meat in the same city, does an even cheekier version, a little beignet rolled in sugar and stuffed with beef marrow and tart cherries.

Still, if the doughnut has gone uptown, the principle is the same. And what a principle. The notion of dunking blobs of dough in vats of boiling oil has gratified taste buds for eons. Every culture has its version, from Poland’s paczki, to Italy’s zeppoli, to Indian vadai, a savoury snack that’s a dead ringer for a doughnut. But the doughnut, dusted with sugar or injected with pudding, sold piping hot at fairgrounds or coming off Rube Goldberg industrial assemblies, has a whimsy all its own. Chefs like making it. “The fun part is that they bob around in the oil like duckies in the bathtub,” the chef Michael Psaltis told the New York Times. Perhaps that was the allure for Alain Ducasse, who did one for a time, or why Bobby Flay invited Mark Isreal for a recent Throwdown! (Isreal won.) The doughnut encourages playfulness. “It’s completely malleable, a blank slate,” said Kirsten Anderson of Glazed Donuts Chicago, who has come up with such exuberant creations as mint mojito and Bing cherry balsamic. Isreal admitted his own inventions have occasionally gone too far for clients: basil, fig, even black sesame. “The doughnut was black and people were freaking out,” he said.

The artisanal doughnut is, despite its modern appearance, a reprisal rather than an invention. The first doughnuts were artisanal: “cakes mingled with oil, of fine flour, fried” are mentioned in the Bible, although it was likely the Dutch, who brought the oliekoek (“oily cake,” literally), a sort of ur-doughnut, to the New World. The treat caught on, their name for it thankfully not. The historian and author Charlotte Gray notes in a speech about doughnuts for a Royal Ontario Museum event there are recipes for beignets in Canada’s first cookbook, La Cuisine Canadienne, published in 1840, and that they were a hard-won treat: “The cook would be cooking over an open hearth?.?.?.?in a dimly lit cabin during winter.”

Labour aside, there is a science to doughnuts. “It’s one of the simpler things, but the simpler something is, the more difficult it is to get perfect,” said Chow, who trained as an engineer before going to culinary school. “My dough is like my child,” said Anderson. “I know how the doughnuts are going to behave based on the way the dough feels, looks, handles.” And every doughnut is a little different. Anderson has just one rule: cake doughnuts only. “Yeast is for bread,” she proclaims.

That’s a controversial point. There are two schools of thought, one favouring the raised doughnut, made with yeast, the other the cake. (Chains like Tim Hortons sell both.) Taste them, and the difference is immediately apparent. The raised is lighter, fluffier, chewier. The cake is denser, heavier—and better, say its fans. “An honest-to-god sinker has the specific gravity of lead [and] won’t crumble into nothingness, like its yeast [brethren], when introduced to coffee,” says one aficionado online. “People who know doughnuts know about cake doughnuts,” said Anderson. “They’re more old-fashioned.” Mark Isreal, whose raised doughnut recipe is based on the one his grandfather, a baker, used in the 1930s, scoffed at this. “That’s a ridiculous statement,” he said. “Cake dough is for muffins and pound cakes.” The raised, he believes, is the original doughnut, though he sells cake, too.

Yeast or cake, that old-style doughnut, a sweet but somewhat misshapen eccentric, has all but vanished. There are holdouts, like Granville Island’s cultish Lee’s Donuts—handmade in flavours like honey dip and pumpkin—but the treat most of us know came about in the 1950s, thanks to the doughnut machine invented by Adolph Levitt, dubbed “the Gutenberg of fried foods,” by Steve Penfold, a University of Toronto historian and author of The Donut: A Canadian History. Levitt’s Doughnut Corporation of America—a name that belongs in a Batman comic—waged a campaign to put doughnuts in mouths, transforming a home cook’s treat into a full-fledged mass-produced commodity. Two types emerged, Gray noted: cake and yeast.

Soon there were prefab mixes, and teams of scientists running tests to determine the best fat to fry in, the ideal temperature. And there were doughnut stores: lots of them, selling a standardized product. Few commodities visibly embodied Henry Ford efficiency as the doughnut did, those machines, as Penfold said, churning away in display windows.

Today’s artisan bakers have hopscotched past that era. Anderson makes doughnuts the old-fashioned way, using old-fashioned equipment. “I bought these vintage welded rollers on eBay. Sometimes I fry them in a standard commercial fryer. Sometimes I use a large, heavy-bottomed pot large enough to raise a small child in.” She can make 100 doughnuts an hour, compared with the 160 dozen Levitt’s machines could by 1928. Chow and Parsons, too, take the slow road. “Patience is huge,” says Parsons. “You’ve got to let it rest—we leave it in the fridge overnight—and let it proof.” (Proofing entails letting the dough rise.) “And they’ve got to be rolled out, cut into shapes, and fried right away.”

The revival may in part be tied to the recessionary palate, which is fitting: doughnuts were always a poor man’s treat. It’s also about nostalgia, albeit of an imagined kind; as Penfold says, it’s not as if any of us born after 1930 remember the doughnut of yore. But if chefs are rethinking old favourites like soft-serve ice cream—sold in flavours like “cinnamon bun” and “cereal milk” at Manhattan’s Momofuku Milk Bar—there’s no reason to consign the doughnut to the strip mall. Even the priciest ones are just a few dollars: Thuet’s beignets, beautiful ones based on his grandmother’s recipe, are $3.50 apiece; most cost less. (Canada’s designer doughnuts tend to be more classic than avant-garde.)

Some of the new doughnuts gesture toward healthfulness. The Doughnut Plant uses natural, seasonal ingredients. Delica, the Toronto café opened by Devin Connell, whose parents own Ace Bakery, has sweet, blameless “jammies,” a baked doughnut with a swirl of strawberry jam. And Anderson in Chicago has elevated the doughnut to vegan health food, using whole wheat flour, soybean oil, and fruit instead of eggs—health by stealth.

The true doughnut lover, of course, doesn’t worry too much about such trifles as calories or nutritional value. The doughnut may be cake or it may be yeast, it may be deep-fried and crammed with carbs and fat, dipped in chocolate or topped with lavender, but it is a mouthful of heavenly goodness. And to quote Mencken, the hole, at least, is digestible.

—

Homemade Honey Sage and Sea Salt Donuts

Makes 12 to 16 donuts

Ingredients

• ¼ cup warm water

• ½ ounce instant yeast

• 5 cups flour

• 2 whole eggs

• 1 ¼ cup warm milk

• ½ cup sugar

• 1/3 cup shortening

• 1 tsp salt

• 3 tbsp honey

• 12 fresh sage leaves chopped

• 1 tbsp sea salt

Mix the water and yeast in the bowl of the kitchen aid mixer. Let it sit for 5 minutes and then add 2 cups of the flour, salt, sugar, eggs, milk, shortening and mix on low speed. Add the remaining 3 cups of flour and mix until the dough pulls away from the sides of the bowl. Remove from the bowl and knead the dough for one minute. Cover with a damp cloth and leave to sit at room temperature until the dough doubles in size. Roll out the dough to about 1 inch thick and using a cookie cutter, cut into small rings. Again place on a baking tray, cover with a damp cloth and leave at room temperature until the doughnuts in size. Deep fry immediately at 350 degrees until golden brown. Just before serving drizzle with honey, sea salt and chopped sage. (Recipe by Jason Parsons)

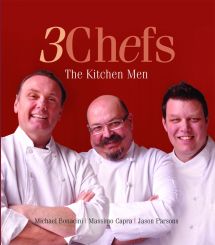

Printed with permission from Three Chefs: The Kitchen Men, by By Michael Bonacini, Massimo Capra, and Jason Parsons, forthcoming from Whitecap Books/Madison Press this fall.

Printed with permission from Three Chefs: The Kitchen Men, by By Michael Bonacini, Massimo Capra, and Jason Parsons, forthcoming from Whitecap Books/Madison Press this fall.