David Chariandy wins 2017 Rogers Writers’ Trust prize

The Toronto-born writer takes home one of Canada’s biggest literary prizes

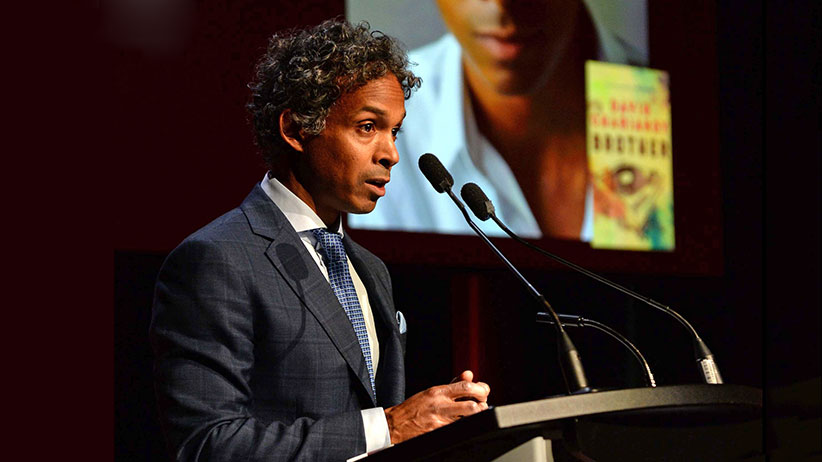

David Chariandy accepting the Rogers Writers’ Trust Fiction Prize. (Tom Sandler)

Share

Last night David Chariandy, 48, won the Rogers Writers’ Trust Fiction Prize for Brother, a novel both beautiful and politically charged. The parallel with Chariandy’s mentor and friend Austin Clarke was inescapable and clearly moving for him: Clarke, who died last year at 81, took the inaugural WT prize 20 years ago; Chariandy is the first winner of the since the prize money was doubled to $50,000 this year. As he usually does in public comments and in interviews, Chariandy—an academic deeply conscious of the long, interconnected history of black writing in North America—paid tribute to Clarke in his acceptance remarks.

Asked afterwards what he and Clark would have been talking about in the moments after the announcement, it was the literary and not the political that came to mind. “When I was nominated for a prize before, Austin always told me to ignore the thought of winning but enjoy the moment, because that meant I had done something important—finished the draft, completed the work, written something. That was our special kinship, being part of a line of black writers and thinkers, and that’s what we’d be talking about, where we are now.”

The evening’s non-fiction winner was James Maskalyk, who won the $60,000 Hilary Weston Writers’ Trust Prize for Life on the Ground Floor: Letters from the Edge of Emergency Medicine. With his moving and penetrating account of his experiences as an emergency room doctor in hospitals from Toronto to Ethiopia, Maskalyk joined a centuries-old tradition of doctors who write well. There are a lot of theories about why doctors stand out in their literary abilities, including training as acute observers who are also taught to be conscious of their own reactions to trauma. Maskalyk doesn’t disagree with those concepts, but he considers the root cause to be simple: “The stories come to us, and we get to ask intimate questions that people will actually answer. The reason they are at the hospital, their whole stories, will emerge if they are open.” Fair enough, although it still doesn’t explain the ability to tell those stories so well.”

Read an excerpt from “Brother” here.