How the zero-waste movement is changing fine dining

Through creative reinvention, chefs are turning scraps, peels and seeds bound for the trash into culinary treasures.

This tomato salad, from the Acorn in Vancouver, is made with compost-ready cast-offs. (Photograph by Lorenzo Ignacio)

Share

There are few dishes as luscious as a tomato salad at the height of the season. At the Acorn, a haute vegetarian restaurant in Vancouver’s Riley Park neighbourhood, head chef Devon Latte drizzles wedges of jewel-hued tomatoes with a vinaigrette and contrasts their sweetness with a creamy homemade mayo. He textures the dish with cheese and croutons, then showers it with basil. What diners don’t see are all the scraps that Latte has layered onto the plate: the tomato leaves used to make that verdant, herbaceous vinaigrette; the scraps of tomato reduced with caramel to make a savoury, silky sauce; and even the mayonnaise, made with chickpea miso and smoked tomato scraps, and emulsified with leftover aquafaba.

The Acorn is one of a growing number of Canadian restaurants subverting expectations about fine dining through the thrifty, ingenious use of ingredients that other kitchens might toss in the compost or garbage bin. Scraps, peels, seeds, cores, leaves: through creative reinvention, these change from trash into culinary treasure. As the food world faces more pressure due to the climate crisis and skyrocketing inflation, zero-waste restaurants offer an intriguing template for how the industry can adapt. Like veganism is to vegetarianism, zero-waste aspires not to limit waste but to nearly eliminate it altogether, without compromising on the quality of the dining experience. And restaurants are gaining recognition for it: the vaunted Michelin Guide began awarding “Green Stars” in 2021 to recognize exceptional sustainable restaurants.

MORE: This Iranian-Canadian food stylist is raising awareness with these stunning dishes

In zero-waste kitchens, chefs don’t throw out any ingredients until they’re well and truly used up: pickled for preservation, simmered for stock, squeezed for every last drop of flavour. At the Acorn, celeriac skins are fermented into complex bases, peach pits transform into syrups and kiwi skins turn into powders dusted over dishes—reframing food scraps into fine-dining adventures. The end result is not one of conspicuous sustainability, but of innovative presentation and surprising flavours. We go to restaurants for culinary epiphanies, and the zero-waste approach shows us what we’ve been missing all this time.

The zero-waste movement entered the mainstream in the 2010s, when blogger Lauren Singer made headlines for fitting four years’ worth of trash into one mason jar. Interest has escalated gradually since then: in 2016, the Saskatoon chef Christie Peters, owner of the acclaimed restaurant Primal, hosted a zero-waste dinner that featured dishes made from vegetable stems, butcher trimmings and stone-fruit pits. And in July of 2021, 29 Canadian restaurants and bars participated in a global “Zero Waste Month,” designing cocktail recipes that incorporated scraps and peels. Initiatives like these signal a growing interest in sustainability from restaurants and consumers alike. They also reveal how challenging it is to shift consumption patterns across an industry.

Shira Blustein, the Acorn’s owner, has focused on sustainability since the restaurant opened in 2012. “Restaurants are notoriously wasteful,” she says, estimating that in a typical kitchen, one- to two-thirds of all produce is trimmed and discarded. A recent federal report, meanwhile, found that kitchens in hotels, restaurants and other institutions waste almost 40 per cent of their produce. Even before the food is prepared, it’s often delivered in large quantities by suppliers, swaddled in packaging that goes straight into the dumpster.

A zero-waste philosophy is good for a restaurant’s bottom line because it maximizes each ingredient’s value. “If you’re paying for the roots and carrot tops, you might as well use them,” Blustein says. The process requires considerable planning, not just day to day but season to season. The staff at Big Wheel Burger in Victoria turn food scraps, wrappers and plates into compost and convert used oil into biodiesel to fuel their restaurant van. The Acorn preserves, pickles and cans as much summer produce as possible, which helps cut down on food costs in the winter. Reducing waste, according to Blustein and Latte, isn’t particularly difficult, nor does it involve special training. It does mean spending more on kitchen labour—perhaps the greatest roadblock to its widespread adoption. And yet Blustein and Latte have found that being thrifty with food scraps can help offset labour costs, resulting in a sustainable equation that has kept their doors open for over a decade.

Waste reduction doesn’t end in the kitchen—restaurant staff must consider where the food comes from, how it’s transported, and what happens after it leaves the kitchen. At Primal, the kitchen practises whole-animal butchery to ensure it uses up each part of the animal; kitchen staff use the bones for stock, then grind them into compost.

This dedication—and the labour needed to process each ingredient—translates into a premium price tag. The tomato dish at the Acorn is $23, and a plate of spaghetti and meatballs at Primal is $32. Blustein believes that the quality of the ingredients, and the kitchen’s efforts to extract a symphony of layered flavours from each, justifies the cost. “People are always surprised by how good peak-season food is,” she says. “You’re never going to get anything like it at Safeway or Superstore.”

To increase support for these kinds of sustainable restaurant practices, diners will have to start caring a lot more about what goes into their food: how it was grown, where it came from, how it was prepared. Restaurants have always sold us on the plated dish; zero-waste requires us to look beyond it. The strongest case for this approach comes from the food itself. “When you take a peach that has ripened on the tree, and it comes directly to our restaurant without ever seeing a fridge, it’s absolute perfection,” Blustein says. “There’s nothing better than that.”

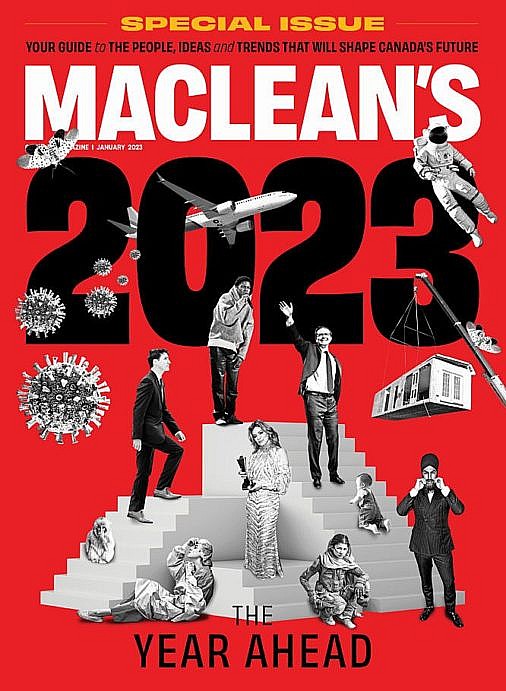

This article appears in print in the January 2023 issue of Maclean’s magazine. Buy the issue for $9.99 or better yet, subscribe to the monthly print magazine for just $39.99.