The Power List: Galen Weston is the country’s most powerful—and controversial—grocery mogul

While Canadians struggled to pay their weekly grocery bills, Weston has received heat for his astronomical wealth

Share

Food Titans

No.1: Galen G. Weston

READ: The Power List: Food top 10

Galen G. Weston knows us better than we know ourselves. As president of Loblaw, a subsidiary of George Weston Ltd., his roughly 2,500-location retail operation includes some two dozen grocery store and pharmacy banners like No Frills, Shoppers, T&T, Valu-mart, Zehrs and Real Canadian Superstore; virtual health care at PC Health; personal banking at PC Financial; and fast-fashion marvels at Joe Fresh. He knows what’s in our kitchen cupboards and medicine cabinets, and you’ll even likely receive eerily timed coupons for frequently purchased items in your inboxes and in-app offers. All that customer knowledge pays off: Loblaw makes $53 billion in annual sales, nearly twice that of Empire Co., its closest national competitor and the parent company of Sobeys.

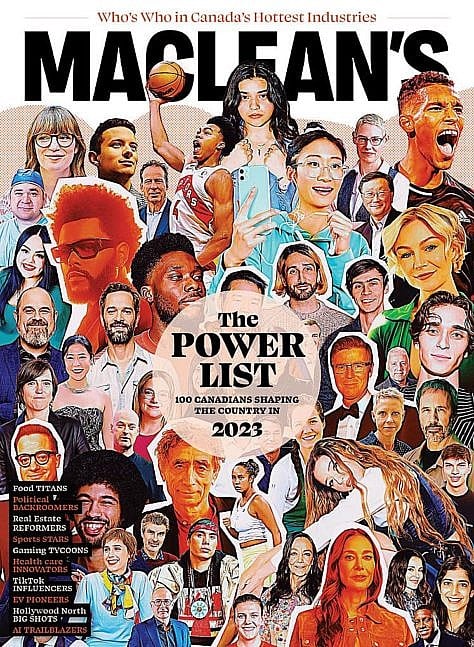

MORE: See who made the 2023 Maclean’s Power List

At the beginning of the pandemic, Weston won kudos for topping up the wages of his stressed-out front-line workers and keeping food on the shelves. The goodwill didn’t last. Last fall, as food inflation hit a 41-year high and social media reached a frenzy over outrageous prices for grocery staples, the op-ed pages and Parliament Hill fixated on the big three grocers: Metro Inc., Empire Co., and Loblaw. They all posted higher profits in the first half of 2022 compared to their average profits over the past five years, with Loblaw raking in the most. MPs called for hearings into the so-called “greedflation.”

Weston announced in October that he’d freeze prices on his bargain line of No Name grocery products, but only until the end of January so people could have a nice holiday. In a letter to his PC Optimum customers, he said he felt their pain, but was met with trending doctored photos on Twitter of him wearing an oversized gold crown, or a No Name–yellow sweater emblazoned with “oligarch.”

I beg your pardon pic.twitter.com/3IIlc7xtY6

— Siobhan Morris (@siomoCTV) January 4, 2023

While Canadians struggled to pay their weekly grocery bills, Weston has received heat for his astronomical wealth. He earns $5.4 million annually, according to his last publicly reported compensation in 2021, which means he takes home more in a week than the average Canadian does in a year. He owns an estate outside Toronto, a family compound on the Florida coast and an entire island in Ontario’s Georgian Bay. Over the course of the pandemic, the value of his family’s shares in George Weston Ltd., founded by his great-grandfather and led by Weston as CEO, have swelled from $5.9 billion to $10.8 billion.

Weston has argued that grocers aren’t to blame for inflation. Fault manufacturers and distributors for jacking up prices, the Ukraine war’s disruption of international wheat supplies and fertilizers, the pandemic’s persisting supply-chain messes and labour shortages, and the freaky floods and droughts driven by the climate crisis. His company denied allegations that they’ve profited from inflation, attributing their success in part to bolstered sales in higher-margin categories like beauty products. Loblaw’s gross profit margins in food were flat in comparison, according to their chief financial officer. At the December parliamentary hearings on food inflation, after MPs summoned CEOs of major grocers, Loblaw sent a deputy.

RELATED: The food supply chain and why groceries are so pricey right now

Weston wants Canadians to blame the supply chain for inflation yet skirts over the fact that, in not-insignificant ways, he is the supply chain. He’s the manufacturer of thousands of President’s Choice and No Name private label products. Those same products outsell many other national brands. His company is also one of the biggest distributors of grocery products, from 23 warehouse complexes across the country—and the only available supply option for many independent grocers. He also just broke ground on a new fully automated distribution centre north of Toronto that’ll sprawl across 1.2 million square feet.

Grocery inflation won’t end in 2023—a group of academics at Dalhousie University predict that the average Canadian family of four will spend $1,065 more on groceries this year due to inflation. McMaster University economist Jim Stanford recently weighed in, deciding that the grocery industry’s “flat profit” numbers don’t add up. He cited StatsCan data showing that Canadians are buying fewer groceries now than before the pandemic, but paying far more for them. The average food retail net margins have grown by three-quarters since the pandemic, from 1.62 to 2.85 per cent. Food and beverage retail has ballooned in annual profitability by $2.8 billion since 2019, making it one of the top 15 most profitable sectors in the economy (oil and banking remain on top of the pile).

MORE: Food insecurity in Canada by the numbers

Weston has created a company that tracks and knows its customers, prompting them to find everything they need at his stores. But as consumers feel the squeeze as their bills pile up higher than before, his challenge for 2023 is to figure out how not to drive them away.

Check out the full 2023 Power List here

This article appears in print in the March 2023 issue of Maclean’s magazine. Buy the issue for $9.99 or better yet, subscribe to the monthly print magazine for just $39.99.