Harvey Weinstein and the theatre of victim blaming

Anne Kingston: Foisting responsibility on the accusers deflects attention from the systems that protected—and continue to protect—Weinstein

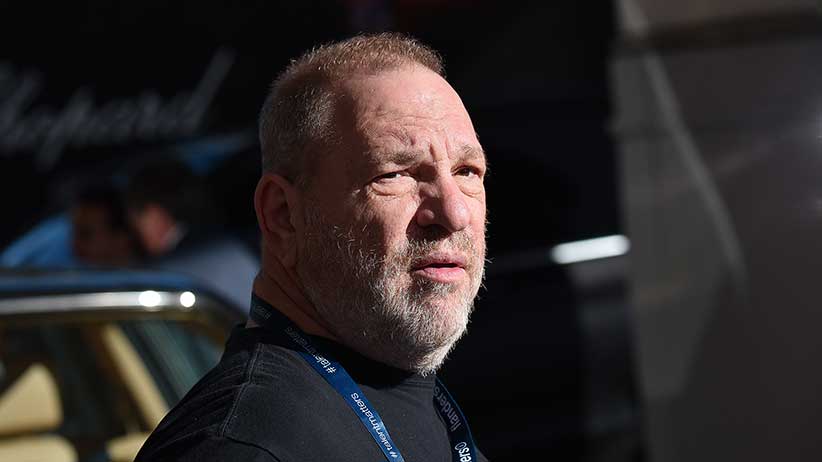

TORONTO, ON – SEPTEMBER 09: Producer Harvey Weinstein and actor/director Dustin Hoffman attend The Weinstein Company film premiere party hosted by Grey Goose for “Quartet” at Soho House Toronto on September 9, 2012 in Toronto, Canada. (Photo by Jeff Vespa/Getty Images)

Share

Since last Thursday, when the New York Times published its Harvey Weinstein exposé, a steady stream of brave women have stepped forward to report being sexually harassed and sexually assaulted by the powerful producer. An investigation published by the New Yorker on Tuesday included stories from 13 women that made for distressing reading; three reported Weinstein had raped or sexually assaulted them. Hours later, Gwyneth Paltrow and Angelina Jolie joined a new group of women who said they too had been harassed by Weinstein when they were starting out. On Wednesday, the model-turned-actress Cara Delevingne shared on Instagram her own “terrifying experience” which included Weinstein telling her that gay actresses don’t get hired in Hollywood before trying to kiss her in a hotel room. All of these accounts share a horrible sameness: first, the women’s disbelief, then their sense of panic, then the internal calculations and negotiations they made while feeling powerless, then the inevitable self-reproach; it was as if Weinstein had perfected a self-blame eco-system. Many women reported the trauma transformed their lives.

As the testimonies emerged, so did another depressing pattern: blame being deflected away from Weinstein—and the institutions that protected him—onto the women he victimized, even women he didn’t. Designer Donna Karan, a Weinstein friend, actually suggested the women might be have been “asking for it” by wearing provocative clothing in a videotaped interview (she later said her comments were taken out of context). An op-ed in the Independent whined that women who accepted financial settlements with non-disclosure agreements, as at least eight did with Weinstein, are doing “nothing for other women,” before explaining why they sign them: “Time and time again, women think they won’t be believed and accept money to keep their mouths shut.” The piece ended with a scold: “Making that choice doesn’t help other women.” Yes, let’s attack a young woman trying to make a living in a precarious, competitive industry, not the monstrous behaviour that creates the market for NDAs in the first place.

The idea that it’s women’s job to help other women, as opposed, say, to a man’s job not to criminally assault them, fuels the barrage of criticism levelled at women now coming forward, including Jolie and Paltrow. That even A-list actresses were reticent to report speaks volumes about Weinstein’s power—as well as a reminder the entertainment industry is not the liberal bastion it pretends to be. Women are expected to placate, to get along, lest they be seen as aggressive and disruptive (read: unhireable). They’re the sexual gatekeepers: if something goes awry, they shoulder the blame. Even Paltrow, who hails from a privileged show business family (Steven Spielberg is her godfather), wasn’t immune from Weinstein’s aggression.

READ MORE: The Harvey Weinstein scandal explained

The blame game even extended to Meryl Streep, who once called Weinstein “God” while accepting an Oscar (at the time, it wasn’t an overstatement in Hollywood). After the Times report, Streep issued a statement calling Weinstein’s reported behaviour “disgraceful,” a quaint word under the circumstances. She added that this was the first she’d ever heard of it. Given that Weinstein’s piggish behaviour was one of Hollywood’s most open secrets, it was difficult to believe. Then again, Streep is three years older than the 65-year-old Weinstein; she’s not his preferred female age demographic. Having won Oscars by the time he rose to prominence in the ’80s, she also wasn’t ripe for intimidation. Guessing whether Streep knew or not about Weinstein is an interesting parlour game, but it’s academic: she wasn’t the one standing in a hotel room in an open bathrobe implicitly threatening to strip a woman of her livelihood and reputation.

That dynamic was spelled out by actor Heather Graham, who wrote of her experience with Weinstein in a piece published Tuesday in Variety. She recalls being invited to Weinstein’s office; he had a movie for her, he said, before announcing that his wife let him sleep with other women. Later, he asked to meet with her in a hotel room. Graham, who’d heard the rumours, asked a girlfriend to go with her. When the friend dropped out, Graham cancelled, not without Weinstein bullying her. After, she wrestled with “the gray areas,” Graham writes: “Did what I think happen just happen?” She describes a classic “gaslighting” move: “He didn’t explicitly offer a trade—sex for work—even though I knew that was what he was implying.” Fostering such uncertainty prevents women from coming forward, she said: “We don’t want to be attacked for reading into something that may or may not have been there.”

Foisting the blame on the accusers is a reflexive response in sexualized violence cases. In this instance, it deflects attention from the systems, legal and institutional, that protected and continue to protect Weinstein. One appears to be NBC. In an interview on the Rachel Maddow Show on Tuesday, Ronan Farrow, a freelance NBC contributor who wrote the story published by the New Yorker, said the network spiked the story, even though it was ready to go. Why isn’t clear; Weinstein is famously litigious; NBC also does business with him. The relationship could explain the surprising absence of Weinstein-related jokes on NBC’s Saturday Night Live last weekend.

READ MORE: Weinstein’s downfall creates a moment of reckoning for Hollywood

The New Yorker also shared a tape from a 2015 NYPD sting operation in which the movie mogul confessed to assaulting model Ambra Battulana Gutierrez. No charges were laid. It wasn’t the first time Manhattan D.A. Cyrus Vance Jr. showed disinclination to prosecute the rich and the powerful. (The New Yorker recently revealed Vance, who’d received re-election funding from a Trump lawyer, chose not to prosecute Ivanka Trump and Donald Trump Jr. for fraud and larceny.)

Money and clout infest every aspect of this story. It’s evident in the condemnations released by people once close to Weinstein. On Tuesday, actor Leonardo DiCaprio issued a statement that said in part: “There is no excuse for sexual harassment or sexual assault—no matter who you are and no matter what profession.” Barack and Michelle Obama, whose eldest daughter interned at the Weinstein Company, made a joint statement about the prominent Democratic Party donor that included a similar caveat: “Any man who demeans and degrades women in such a fashion needs to be condemned and held accountable, regardless of wealth or status.” The “regardless of wealth or status” in that sentence is telling: it implies Weinstein’s wealth and status did confer privilege, untouchability, special status.

And he did make people famous, he made people rich, he made a lot of people beholden to him. Now a famously vengeful man has been ousted from the company he co-founded; his wife has announced she’s leaving him. Yet it’s a testament to Weinstein’s enduring confidence and arrogance that he believes a comeback is possible. The first stop is rehab for “sex addiction,” TMZ reported; Weinstein and his team are also in settlement discussions with the Weinstein Company: “the idea of him serving in some outside capacity is still on the table.”

Weinstein’s problem isn’t “sex addiction,” of course. It’s “power addiction,” or rather exploiting his formidable power to intimidate and control. That’s what got him off. And there’s no rehab for that.

Meanwhile, the women Weinstein tried to intimidate and control wrestle with their own self-blame: “I was so hesitant about speaking out,” Delevingne wrote. “I didn’t want to hurt his family. I felt guilty, as if I did something wrong.” Graham expresses remorse tinged with optimism: “While I still do feel guilty for not speaking up all those years ago, I’m glad for this moment of reckoning.” Let’s hope she’s right. But the reckoning can’t begin until the victim-blaming ends.

MORE ABOUT HARVEY WEINSTEIN: