Hijra sex workers at the centre of Anosh Irani novel

A deeply researched novel anchored by relationships

Share

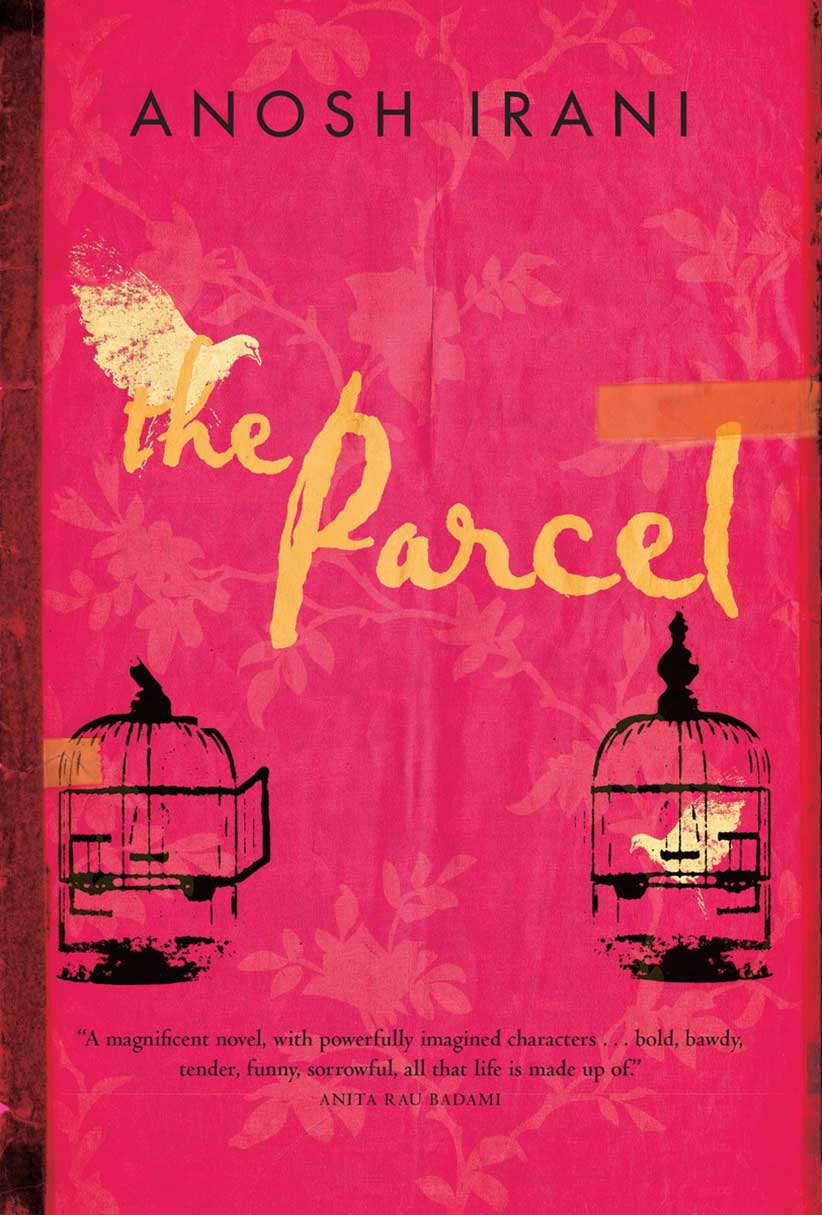

THE PARCEL

By Anosh Irani

This novel about hijra (transgender) sex workers in contemporary Mumbai contains a fair amount of disturbing description, including a castration performed in a less-than-clinical setting with tightened ropes used in place of anaesthetic. And yet The Parcel’s most discomfiting aspect is its central metaphor, a “parcel” being a prepubescent girl stolen from her family and sold to a male client who will “open” her.

Our protagonist, Madhu, a 40-year-old hijra eunuch, has made of the parcels a kind of calling. Though demoted by her gurumai (guru) to begging in the streets, during her years as a prostitute Madhu developed a way to humanely “break” them without recourse to pain and torture. As the novel begins, she’s just been summoned by the district’s fearsome brothel owner, Padma, who tells her that a new parcel has arrived. Though Madhu initially protests on the grounds that she’s retired, we know her acceptance of the task is inevitable.

The 10-year-old Nepalese girl waiting in a small cage isn’t outwardly different from other parcels. Yet she triggers something in Madhu. For us, she triggers a series of flashbacks to Madhu’s boyhood, his rejection by his father for effeminate behaviour and subsequent “rescue,” at 14, by the gurumai who would become his physical guardian and spiritual leader. Now, 30 years after meeting the gurumai, Madhu suddenly wonders if her family might not be ready accept her as the woman she was meant to be.

Relationships—between Madhu and her parents, her gurumai, her erstwhile lover and even the parcel—anchor this novel, yet they tend to be psychologized rather than evoked (“Her father’s scorn had been replaced by society’s”). There’s a dash of Hollywood melodrama, too, to Madhu’s nightly vigils spent staring longingly into people’s homes, a habit she calls “her smack, her ganja.”

To be sure, the exhaustive, sometimes vivid detail with which Vancouver-based Irani depicts hijra customs, brothel life and the world of sex trafficking suggests much research. But knowledge, or rather the impulse to share it, can be a mixed blessing for fiction, and that often proves the case here. This being a novel seeking to answer, rather than provoke, inquiry, the feeling of fullness we get by the end is ultimately more pedagogic than aesthetic.