John le Carré delivers a vibrant memoir

John le Carré on his life as a spy, a writer of fiction and now a memoirist

Share

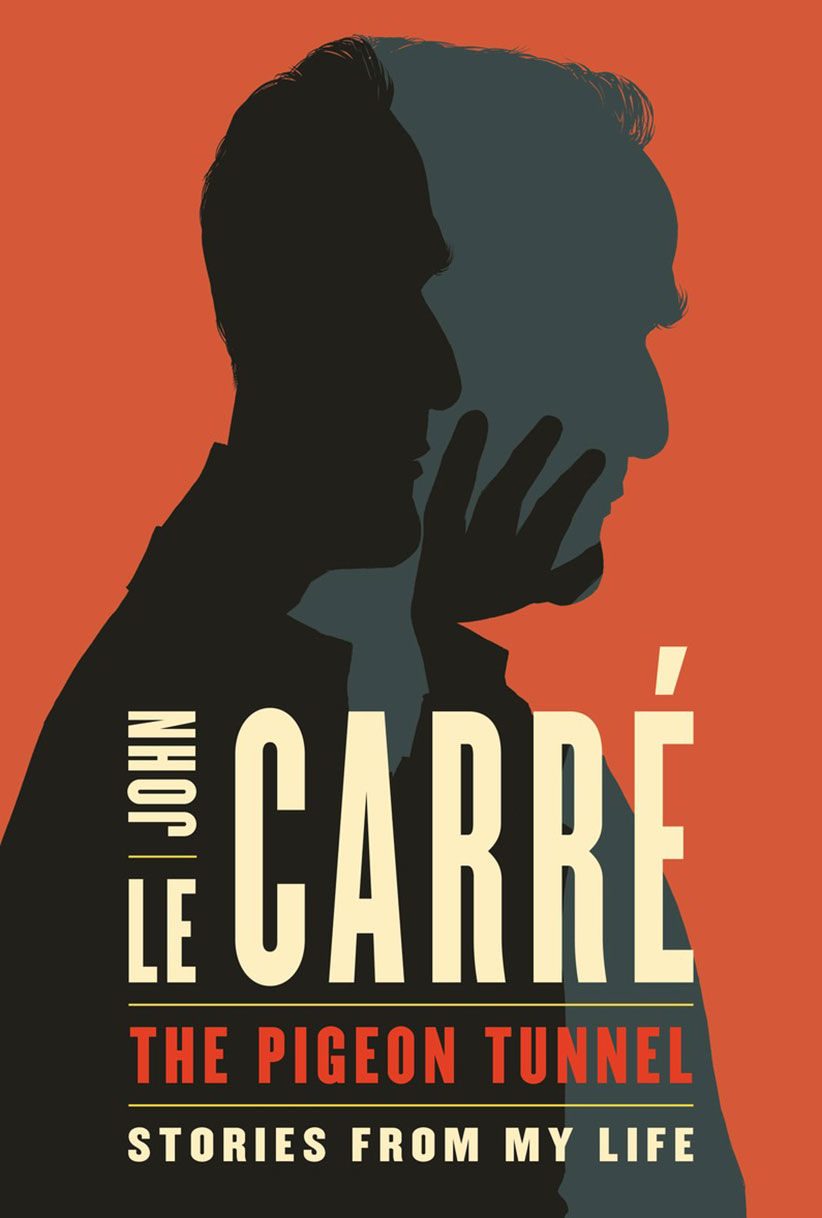

THE PIGEON TUNNEL

By John le Carré

A teenaged John le Carré (a.k.a. David Cornwell) first saw a pigeon tunnel in Monte Carlo, where his father, Ronnie—con man, philanderer and bon vivant—took him on a gambling spree. Staff at their seaside hotel would insert live pigeons into narrow passages that lay beneath the resort lawn and opened over the Mediterranean. The birds flew frantically through the darkness and burst into daylight over the water, he recalls, only to become shotgun targets for “well-lunched sporting gentlemen.”

The scene haunted le Carré — it so closely parallels the treatment of spies by their masters. Would-be le Carré biographers, meanwhile, came to identify with the pigeons: some fled in the face of legal threats from the famously prickly writer; others took fusillades of invective in the press. It’s odd, then, that this memoir amounts to a kind of appendix to Adam Sisman’s clear-eyed treatment of his mercurial career last year. While le Carré remains ambivalent about John le Carré: The Biography, acknowledging it here without naming it, he by no means challenges it. On the contrary, his collage of scenes complements Sisman’s rendering, infusing it with texture and colour.

And what colour. If Ronnie Cornwell’s example weren’t a life lesson in the credulity and absurdity of humanity, le Carré’s subsequent career was. Assigned to Bonn as a young MI6 agent, he found a West Germany run by former Hitler enablers, whose rise British diplomats tactfully ignored. Later, literary fame brought him face to face with history’s prime movers, from Margaret Thatcher to Rupert Murdoch. He was summoned to keep watch over an over-refreshed Richard Burton during filming of his The Spy Who Came in from the Cold. While researching The Little Drummer Girl, he found himself in a New Year’s conga line behind Yasser Arafat.

Le Carré at times betrays British tendencies he professes to loathe. The wit can seem arch; the professions of humility strained (“I felt, as I feel today, that I was not cut out for our honours system, that it represents much of what I dislike about our country”). Devotees will be let down by his refusal to tell spy tales out of school. But even as he irks, le Carré beguiles — a talent both learned and inherited from his ne’er-do-well father. In his lives as a spy, a writer of fiction and now a memoirist, it has served him well.