Julia Child’s life in America

A follow-up from Alex Prud’homme on his aunt Julia Child, the original celebrity chef

Share

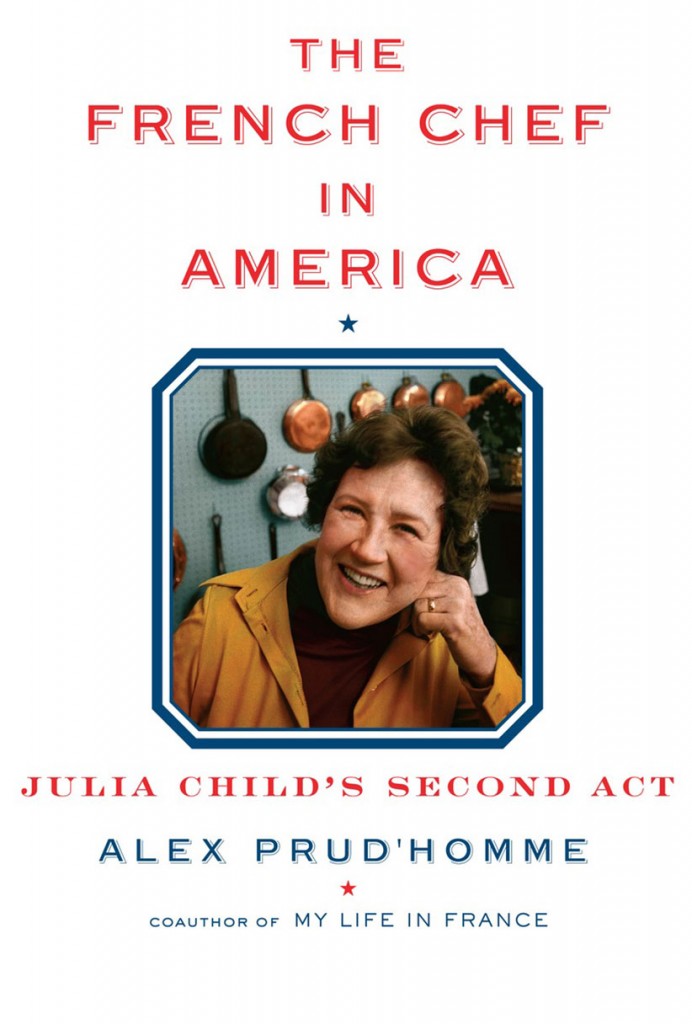

THE FRENCH CHEF IN AMERICA

By Alex Prud’homme

Before there was the Food Network, there was Julia Child. She wasn’t the first celebrity chef to appear on U.S. television—that honour went to her friend James Beard in 1946—but she was the first to do it well. With a personality worthy of satire on Saturday Night Live (thank you, Dan Aykroyd), Child pioneered the genre of affable performer-instructor-author that we recognize today. This book is a sequel to My Life in France, Child’s ripsnorting memoir published posthumously with co-author Alex Prud’homme in 2006, two years after her death. Writing solo this time, Prud’homme has produced a follow-up book about his great-aunt that is equally fast-paced, loaded with “kitchen porn”—gadget talk and descriptions of feasts—and gossipy asides.

He starts right in with Child’s debut on PBS in 1963. We read about the agony of producing Volume 2 of her bestselling cookbook, Mastering the Art of French Cooking, with co-author Simone Beck. Prud’homme next charts Child’s rebranding of herself as an all-American cook. It was a bumpy transition. For a time, at least, Child reversed her negative opinion on many things, including MSG, fast food, GMOs and even supermarkets. Where did she stand on nouvelle cuisine? At first, she feared it was the end of traditional French cooking, but she eventually embraced its creativity. Child also derided vegetarians, dieting and organic food in their early days.

Politically, she identified as a liberal democrat and openly supported Planned Parenthood, yet she extolled the virtues of marriage and homemaking. Child swore off television several times, then always went back on air. What emerges is a portrait of a driven, flexible mogul with boundless energy, who won her last Daytime Emmy at age 88. She was also a nurturing mentor who helped launch the careers of protégés Emeril Lagasse and Sara Moulton, among others. (CanCon alert: Child sent an early-model Cuisinart to Dan Aykroyd’s aunt, Helen Gougeon, who was Child’s Canadian counterpart, with a weekly television show on the CBC.)

Prud’homme’s bias is revealed when he describes Child’s critics as jealous polemicists, but that can be forgiven. His real forte is analyzing the cultural context for Child’s postwar career in America. The U.S. was ready for someone to democratize fine dining and make cooking fun. That was Julia.