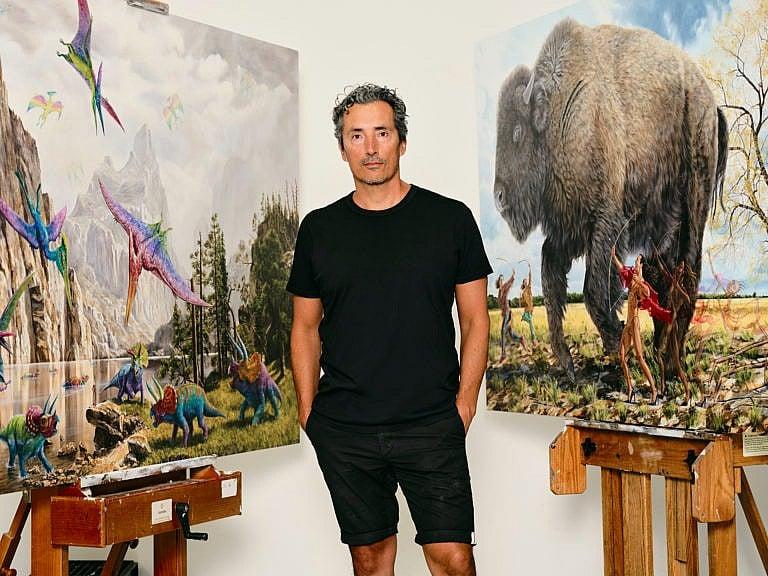

How Kent Monkman’s alter ego is challenging colonial history

Through the lens of his glamorous alter ego Miss Chief Eagle Testickle, artist Kent Monkman amends the historical record.

(Photograph by Claudine Baltazar)

Share

The Cree artist Kent Monkman has a striking alter ego: Miss Chief Eagle Testickle, a time-travelling, shapeshifting, gender-fluid agent of imagination who appears in many of his works. With her flowing dark hair, glamorous outfits and red-soled Louboutin heels, she stands out in Monkman’s work alongside his depiction of settlers and colonists. The contrast is intentionally destabilizing, both funny and deadly serious: in his 2016 tableau “The Daddies,” she brazenly sits naked atop a Hudson’s Bay blanket, holding court among the fathers of Confederation, disrupting the colonial narrative of North American discovery. In 2019, the Met museum in New York commissioned two monumental works featuring Miss Chief. It was her—and Monkman’s—breakout moment on the world stage.

Miss Chief is the star of Being Legendary, Monkman’s ambitious new Royal Ontario Museum exhibition in Toronto. The show features 35 original pieces showcasing Miss Chief’s earthly travels from the beginning of time until now. “I thought about her as a legendary being that fits into Cree cosmology, but her specific purpose is to be our witness,” Monkman says.

Monkman hails from the Fisher River Cree Nation in Treaty 5 territory in Manitoba, and has created art since the 1990s. His richly coloured pieces place Indigenous individuals in settings where they’ve historically been erased. The exhibit is subversive, campy and totally tongue-in-cheek. Miss Chief is the arbiter of that joy, and Being Legendary is, in a sense, her story, told through a text narrative on the walls of the gallery. It begins with her creation, in a celestial riff on Michelangelo’s “The Creation of the Sun, Moon, and Planets.” Other paintings feature real-life Indigenous figures, like Cree astronomer Wilfred Buck and Elder Pauline Shirt, the latter a descendant of one of the men killed at the 1885 Hangings of Battleford, where eight Indigenous men were executed.

Being Legendary celebrates the depth and breadth of Indigenous knowledge, reasserting Indigenous presence and challenging colonial narratives of history. “I wanted Canadians to think about how long we’ve been here, and how deep our knowledge goes,” Monkman says. It’s hopeful to see these figures and ideas immortalized in art. The last portrait, of Buck, with constellations painted above him, brings the story full circle. The exhibit starts where it ends: glittering in the stars.

This story appears in the November issue of Maclean’s.