Maurice Sendak remembered

Sendak initiated a revolution with ‘Where the Wild Things Are’ and other acclaimed works

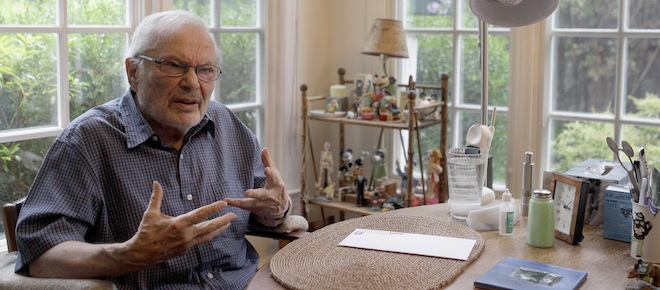

In this Tuesday, Sept. 6 2011 photo, children’s book author Maurice Sendak is photographed doing an interview at his home in Ridgefield, Conn. Sendak is the author of the popular children’s book “Where the Wild Things Are.” (AP Photo/Mary Altaffer)

Share

Maurice Sendak was an artist and writer for children long before identity politics ruled the genre.

Maurice Sendak was an artist and writer for children long before identity politics ruled the genre.

He could have kick-started that move himself, had he a mind to, for if there was ever an outsider of outsized talent capable of upending the prim pre-1960s world of illustrated kidlit, Sendak—poor, sickly, Jewish and gay—was it.

Instead Sendak initiated a different sort of revolution with Where the Wild Things Are in 1963. The hero, cranky, back-talking Max, who could have starred in last year’s Go the F—k to Sleep (more for adults than children, but still a spiritual descendent of Wild Things), makes enough mischief to be sent to his bed without supper. There his imagination lets loose a sea over which he travels to a forest full of wild things, before (of course) making it home to where supper awaits.

The creatures Sendak drew are clearly extreme adults: loud, incomprehensible, hairy almost beyond belief, with unfortunate teeth and bulging, crazy eyes. (It was only after he had drawn them, the illustrator told NPR, that he realized they were the aunts and uncles who often hovered over his childhood sickbed.)

Like most great children’s book authors, Sendak had a note-perfect memory, not of what he thought as a kid but of how he felt. Everyone has been through the same experiences, been to “the same places,” he once said. “Only, I remember the geography, and most people forget it.” Sendak knew children—those walking bundles of id—as well as anyone who has ever created for them, and in Where the Wild Things Are he captured their inner fears and turmoil like few others before or after.

In the half century since, Sendak did acclaimed work designing opera sets, worked on film and TV projects and crafted many more fine books in a life well spent, but Wild Things is legacy enough for anyone.

See also Andrew Coyne’s review of the film Where the Wild Things Are from 2009.