Canada meets Norway in an unsung Oscar veteran’s films

Alex Colville’s rural landscapes meet Marimekko cool in the animated films of Torill Kove

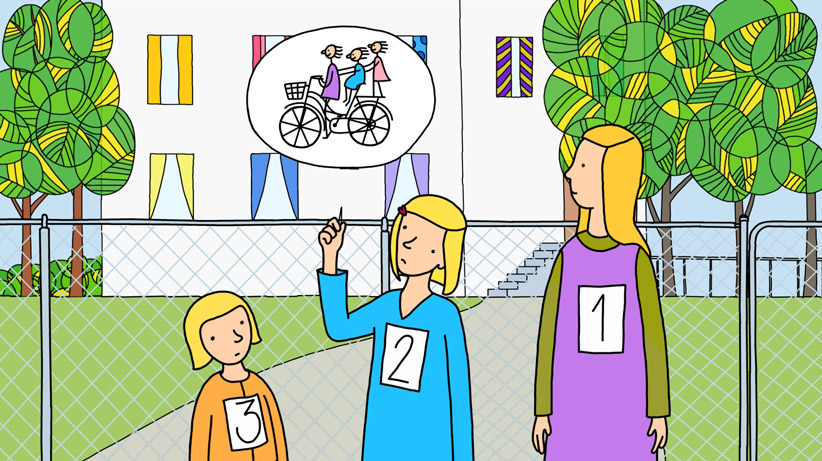

Animation still from the film, Me and My Mouton by Torill Kove. One summer in mid-’60s Norway, a seven- year-old girl asks her parents if she and her sisters can have a bicycle. Me and My Moulton provides a glimpse of its young protagonist’s thoughts as she struggles with her sense that her family is a little out of sync with what she perceives as “normal.” NFB

Share

Can you wear an orange sweater with a blue dress? A seven-year-old girl wants to know. She calls her father, a modernist architect, and asks him the question. His reply: “Blue and orange was a popular colour combination among French royals before the revolution.” The girl considers this, frowns, hangs up the phone, and takes off the sweater.

It is one of the quieter scenes in Me and My Moulton, the third animated short film by the Norwegian-Canadian Torill Kove. On the surface, the girl and her father simply aren’t communicating; she wants a yes-or-no answer, and he wants to educate her. But the voice acting and subtle animation tell us more. The dad, a goofy intellectual, doesn’t care what others think, while his daughter doesn’t care about anything else. “Ten thousand men in our town—one single moustache,” she narrates earlier on. “And it has to be on my dad. It makes my stomach hurt.”

Moulton was released in December 2014, but the fanfare only kicked in once it was nominated for the 2015 Academy Awards for best animated short. The film is a co-production with the National Film Board (NFB), her third, following My Grandmother Ironed the King’s Shirts in 2001 and The Danish Poet in 2006. Each has been nominated for an Academy Award; The Danish Poet won.

Born and raised in Hamar, Norway—“the Norwegian Saskatchewan, except not as flat,” she calls it—Kove moved to Montreal in 1981 to study urban planning at Concordia University, but, during a stint of unemployment in the early 1990s, wound up spending hours at the NFB office on St. Denis, watching films and taking notes. Her style is forged of equal parts Scandinavia and Canadiana: the dark fantasies of Theodor Kittelsen dropped into Alex Colville’s common rural scenes, with illustrations little more complex than Calliou. Her transition into Canadian life was imperceptible. “When I came to Montreal, I thought it was really easy to fit in here,” Kove says over the phone from the city’s NFB office. “The writers I like in Norway, I like because they remind me of Alice Munro.”

Family stories have been her focal point since her debut short, wherein she mythologized her own lineage into a children’s story about heroic matrons staging a “nationwide shirt sabotage” against Nazi invaders. With The Danish Poet, she aimed even bigger, opening with DNA double-helixes floating in space before launching into the invented fairy-tale coincidences that led to her birth.

“The kind of films that I make are a little more . . . demanding, maybe,” Kove says. “I think we Norwegians feel a stronger pressure, or desire, to break down and come up with new and different things—and there’s something in that style I make myself in.”

Moulton is unlike her earlier films, in that it takes place during a particular time (spring 1965) in a particular place (her hometown, Hamar). The lines are cleaner, the animation’s smoother, the background features trees designed like Marimekko fabrics. It’s clearly autobiographical, but sheds the pretence of judgment that might cloud more sentimental work: This is simply about a girl wanting to fit in. Her parents fill their house with three-legged chairs that constantly topple over, and dress their three daughters to resemble a contemporary art installation. The girls want a bike, so their parents buy a Moulton—a quirky British design, but not what the girls wanted. It is a compromise for both sides.

Implanted into the film’s emotional core is an unspoken theme that has resonated strongly with Canadian audiences: Janteloven, or the Law of Jante, a Scandinavian philosophy that stresses humility and forbids thinking too highly of oneself (for instance, by dressing like French royalty in orange and blue). “It’s really ingrained in Norwegians that it’s wrong to do those things,” Kove says. “If someone’s being too modest, someone will say, ‘You don’t have to follow the Janteloven too seriously.’ I used to think it was kind of pathetic, but now I actually like it. It’s a bit like guilt. And guilt is good.”

While Kove isn’t thinking about the content of her next film yet, two things are almost certain: Her work will still be autobiographical, and it will finally take place in Montreal. “I was just looking out my bay window the other day, looking out at the city where I’ve lived for such a long time, this bizarre neighbourhood,” she says. “I just love it.” She lives downtown, not far from the old Forum, and near the decades-old Argo Bookshop and numerous East Asian eateries, an urban mosaic of culture and diversity—and a long way from the Norwegian Saskatchewan.

“It took a long time to feel this is like home, but, in the past few years, I really feel like that,” she says, before pausing. “I think there’s a little Janteloven in Canadians.”