Jonathan Kay: What ‘Coco’ says about the flip side of family love

Opinion: With the holidays upon us, leave it to an animated movie inspired by the Day of the Dead to bust myths about what really defines family life

Share

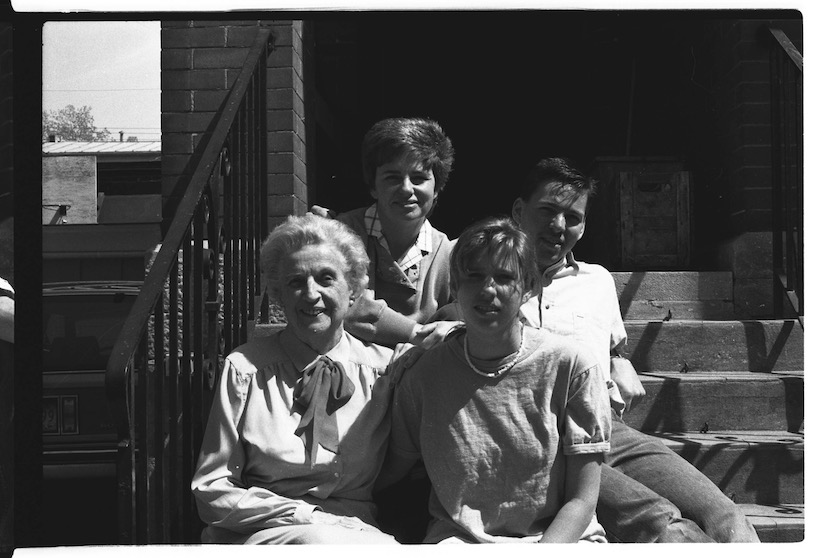

My father’s late mother, a Russian immigrant who lived most of her 96 years in Montreal, was a kindly and gentle old woman. But put Marika at a luncheon table with friends, and things got competitive.

It was my mother who pointed the pattern out to me at Marika’s 80th birthday: From first to last, the conversation revolved around whose son, whose daughter, was most attentive. Which child called every day, came to visit every weekend, took time off work to play escort on doctor’s visits?

I was just a teenager. But in that moment, it dawned on me that every subculture had its pecking order. And for Russian grandmothers of a certain vintage, one’s place on that pecking order comes down to the attentions paid by younger relatives.

It’s one of the reasons I tried to visit every Sunday morning—and called regularly once I moved away for university. It wasn’t so much that my heart ached for my grandmother’s voice. I just didn’t want to see her fall off the local leaderboard. Does that count as “love”? I’m not sure.

The same type of geriatric status competition drives the plot of Coco, the Latin-themed computer-animated holiday blockbuster released by Pixar. But the creators have introduced a morbid twist: the contest goes on beyond the grave.

When someone dies in Cocoland (which feels a lot like Mexico), their skeletal form ascends to a steampunk land of the dead—where they shed the cares of the flesh, and embark on second lives spent laughing, singing and reminiscing with loved ones.

But there’s a catch: Your life in Undead Cocoland lasts only so long as you continue to be remembered and honoured by relatives back in Flesh Cocoland—as symbolized by the ceremonial display of your photo during the annual Day of The Dead. If there is no one left who remembers you, or who cares enough about your memory to tack your picture to the family ofrenda, then you die a second death, and evanesce entirely to planes unknown.

As a science-fiction plot device, this is fantastic. And it drives the action in Coco in all sorts of interesting and genuinely thrilling ways. But for those of us who still feel vaguely guilty about that time in 1988 when we told gramma we couldn’t visit because we had rubella—even though we were just hung over—the concept is horrifying. In the world of the flesh, my failure to do right by an elderly relative might cause her to become lonely and lose face with friends. But once gramma resides in the world of bones, my selfishness can actually kill her. We are talking here about the ultimate gramma guilt trip. (One of Coco’s most important secondary characters, in fact, is a grandmother—as well as a great-grandmother. Her centrality to the plot becomes apparent only in the film’s last few minutes. But the emotional effect is all the more devastating for the waiting. Bring Kleenex.)

Coco has been praised for the way its creators interpreted the cultural traditions of Mexico (where the Spanish version of Coco has broken box-office records). But the film’s true genius lies in the way this superficially whimsical tale captures one of the most profound questions known to the human condition: How much of our lives can be freely lived for our own pleasure and purposes—and how much must be lived in service of kin?

When my 11-year-old and I left the theatre, we both felt emotionally crushed by this theme. Yet we were crushed in different ways. While my daughter’s emotions were caught up with the fate of Coco’s protagonist—a 12-year-old boy named Miguel torn between family loyalty and his love of music—my own emotions were ensnared by a subplot centred on a woebegone Skeleton Cocoland hobo named Héctor, a husband and a father who died his flesh death in a way that caused his memory to be spurned by his widow and kin.

I cannot provide too much detail about Héctor’s backstory without ruining the movie’s many surprises. But suffice it to say that, until meeting Miguel, his life encapsulates every man’s worst fears about his fitness as a father and a husband. And as with everything else in Coco, the torments of loneliness, guilt and regret do not end with the reaper. They are shown to go on and on and on in the bonelands—an endless emotional hell from which the characters are rescued only through the heroism of little Miguel.

This is an unusually sad kind of holiday movie, in other words—but also one that’s no less unusually honest in its depiction of the hidden emotional undercurrents of family life.

From A Christmas Carol onwards, traditionally sentimental yuletide tales have pitted a family against some external threat. Yet the greatest tensions that modern families experience over the holidays often are internal. Like Miguel, children bristle at boring family traditions that keep them away from friends and passions. Parents torment themselves and each other, asking why plans for a perfect Christmas are undone by the venting of a year’s worth of pent-up complaints and recriminations. Grandparents struggle to follow conversations that grow increasingly incomprehensible with each passing yuletide, wondering whether this feast will be their last—and if anyone would even notice if it were.

In the myths we create about domestic life—and peddle to our friends on our Facebook Christmas photo albums—family love is depicted in simple, heartwarming hues. But in their emotional artistry, Coco’s creators drew upon a much richer palette. As with ghosts who hide all year, then make their presence felt on Dia de Los Muertos, the film lets us glimpse the terror, guilt, remorse and insecurity that always exist as the flip side of love.

These are important lessons for my daughter. Or for anyone. Children stop believing in Santa Claus when they’re around 8 or 9 years old. Yet many of us spend our whole lives believing plum-pudding fairy tales about uncomplicated forms of family love that, in this world at least, none of us will ever truly experience.