Pierce Brosnan on how he’d envision a new James Bond

The Irish actor-activist-painter on Donald Trump, working with The Black Panthers and the possibility of a trans James Bond

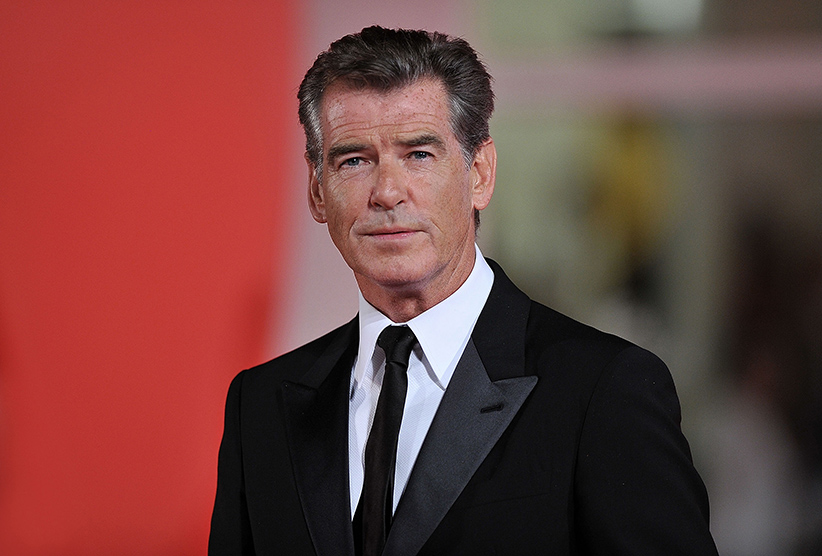

VENICE, ITALY – SEPTEMBER 02: Actor Pierce Brosnan attends ‘Love Is All You Need” Premiere at The 69th Venice Film Festival on September 2, 2012 in Venice, Italy. (Stefania D’Alessandro/Getty Images)

Share

Since his breakout role as TV’s Remington Steele in 1982, Pierce Brosnan has held a monopoly on celluloid charm. The 63-year-old Irish actor, who began his career doing experimental plays at The Ovalhouse Theatre in London, has been able to cultivate the kind of suave predisposition that characters such as Steele, Thomas Crowne and James Bond all require.

His latest role, a return to television after steering clear of it for more than 30 years, has Brosnan starring in an adaptation of Philipp Meyer’s New York Times-bestselling novel, The Son. In this AMC-produced series—which airs on April 8—Brosnan once again showcases his dapper demeanour into a role that urgently demands it. In The Son, Brosnan plays the cruel-on-the-inside, genteel-on-the-outside antihero Eli McCullough, a cattle rancher who aspires to become a successful oil baron. The 10-episode project focuses on the ruthless McCullough, a childhood victim of gratuitous abuse and the father of two sons. On a recent visit to Toronto, Brosnan sat down with Maclean’s to talk about his next career steps, how the Trump administration informed his new role and the future of Bond—and Hollywood itself.

Q: How did your perceptions of Eli McCullough change after playing him for 10 episodes?

A: Well, I loved this story because it is, at its core, a historical drama of a family that is caught in the crosshairs of time. Eli is a man who’s a survivalist. He was born of brutality and savagery. By the time you meet him, he’s lost three families. He’s a man who’s very forward-thinking for his time. He stays connected to his world through the newspaper. He’s an archetypal American mythological hero. Those emblems agreed with me and appealed to me.

Q: What stuck out as the most informative or educational part of this whole process? What did you learn from working in Austin?

A: It was very palpable being there on that Texas landscape in Austin. When you do a costume drama like this—which is so beautifully embroidered by the writing and sets—you do absorb a great sense of history and the terrible sadness of it all. So many people lost their lives in such gruesome ways. The divide of the nation is still relevant in our society and you feel it in Texas. More so than ever now with the president that’s in power.

Q: You’ve had roles as political types in movies such as The Ghostwriter—where you played a publicly shamed prime minister. What tricks—if any—did you use from today’s political spectrum to inform Eli McCullough?

A: I was glued to the TV on a regular basis running up to the [U.S.] election while we filmed. It was compelling. I’d get off a horse, go into my trailer, get a cup of coffee, and watch before my eyes…this epic story of sad Americana history. I can’t believe the U.S. president came from reality TV! In one of the [The Son’s] episodes, there’s a scene where I rally the townspeople. It’s a hateful scene. Eli dissembles in such a bad way in front of everybody. The consequences of that night become this mayhem of violence. Gesturally, I used aspects of this man we call president.

Q: The Trump-ish way you approach Eli is evident in The Son. The scene you are talking about reminded me of what I saw in Trump’s pre-election rallies.

A: I was watching them closely. It’s inciting violence, hate, racism, borders, walls, and shame of a great nation’s politics and forefathers and other presidencies. That idea of having the people right in the palm of your hand…I mean, the man was born of reality TV! He caught the imagination of people who’ve certainly been maligned and left in the wings of society. Now we have him. Eli was born of that—out of watching this terrible behaviour on a regular basis. I’m glad there was some nuance there.

Q: Eli is frequently asked to audition his dreams to these wealthy Texan fat cats. Was there any connection to what actors do in auditions?

A: Oh yes, he knows he’s playing a character. He’s created his own mythology and a rod for his own back. Many actors do this. He’s a star in his own world. His ego is powerful and his presence is powerful. As an actor, you embrace and embellish and work on that within any scene.

Q: What was the greatest challenge for you in Eli?

A: The accent. It was born out of allowing myself to let my own Celtic voice fall into the heartbeat of Eli McCullough. I was constantly listening to various cross-sections of people from Rick Perry to William Jennings, Willie Nelson to Senator Ted Poe.

Q: Eli’s philosophy is “if you don’t move forward, you die.” Is that still true in Hollywood and filmmaking today?

A: You have to move forward. It’s constantly changing. Everything changes and everything falls apart. You have to be nimble and on your toes and accessible to it all. Not everyone is on board with this.

Q: What’s the biggest change you’ve seen in the TV industry, from Remington Steele to now?

A: The censorship. The violence and sexuality on TV today is exhilarating. You can explore every aspect of society. People’s sexual orientations, the violence that goes within that…there are no holds barred. I’d been exploring it for some years prior to The Son going back to TV because I’m a working actor. America gave me the great glory of coming into people’s homes every week and allowed me to last as long as I have.

Q: I want to touch on your theatre upbringing in London. What were the most experimental productions you got into at The Ovalhouse and do they still inform what you do now?

A: So many productions from that time helped expand my range. The Ovalhouse was a glorious beginning to my career. It’s come back into my life in so many ways and so many scenes. They’ve recently asked me to be a patron. They’re now moving into the heart of Brixton on Cold Harbour Lane and are building a beautiful community theatre there. It was an exhilarating time. I left school at 15 with nothing but a cardboard folder of drawings and paintings and dreamt of being an artist. I’d say doing tube theatre made me a little fearless. People would meet us at Kensington Tube station and we’d put on shows for passengers. I remember we made a play called The Family. It was about a young woman who kidnapped a baby. That was my introduction to the arts. Three years of that and I decided I had to get a formal training. I trained at the Drama Center in The Method. I left and started all over again. I was making tea and doing props and putting out flyers and doing plays… and then Tennessee Williams gave me a play and Zeffirelli saw me in the West End. Acting is still a constant work in progress.

Q: What about the theatre helped educate you on the social issues of the time?

A: Well, by 18, I was in the company of dancers and poets and the Black Panthers were having their meetings. I’d run the spotlight and run the shows for when the Black Panther meetings came in. Being an Irishman and living in London…I felt the stab of racism being Irish and not belonging. Because of what I was around, I read about Angela Davis and Huey P. Long…having identification with a society and people that really had fought for freedom and were forging their own identities.

Q: With all this progress you’ve seen in the theatre, TV and movies, do you think we’ll ever see something like a black, transgender, gay, or female Bond?

A: I wish I had the keys to the kingdom. I don’t! The Broccolis [the family that has produced the James Bond franchise since the 1950s] have that and they’ll keep it as is. They will not deviate from the straight white male Bond. It’s highly unlikely. I think it should be different. Perhaps they could create a character who’s a black Transgender spy?

Q: Your character in The Son has a very complex relationship with his two sons. Since you are the father of four, I’m assuming you pulled emotion from your own life?

A: I believe you can only draw from your own life as an actor. All the characters I’ve played whether it be…in The Matador or Bond or Mamma Mia or The Ghost Writer or Eli, they’re all Pierce. I only have my infinite eye and the presence of my life to take from. I know the trials and tribulations of being a father, bringing up young men, and the dark corners they take you to in your heart. That came relatively easily.

Q: You used to say cinema was a sanctuary for you when you were starting off. Is it still?

A: No. I love movies, don’t get me wrong. But I don’t go to the cinema. I see movies at the end of the year as a glut from the Academy. I binge-watch all the nominated films. Painting fills that void now. It’s oils. It’s acrylics. It’s figurative, portraits and landscape.

Q: Will there be an exhibition of your works soon?

A: We’re talking about one in Paris. There’s a gallery there. I can’t say who it is at the moment but it’s right there on the Champs-Élysées. I’ve also always liked the idea of a book or a memoir. I’ve been asked. I have sons so I’d like to leave some scratchings of memory to say “this is how it was,” before someone comes in and twists it.

Q: One of your favourite authors is Aldous Huxley. What did reading him at such a young age do for you?

A: He allowed me to travel in my own universe and be free of anyone’s preconceptions. It gave me the strength and the courage to dream and experiment. Not that I got into drugs—they always scared me. Chemicals! Yikes!

He gave me freedom to be an artist. His writings make me think…why not? If I can fucking sing in Mamma Mia, I can hang some paintings up and be a painter.

Q: Speaking of Mamma Mia, how was it working with the apparently highly overrated Meryl Streep?

A: Trump is such a philistine for saying that—the man couldn’t be more wrong. Seriously though, the morning we put the tracks down, looking at Colin Firth’s face and Stellan Skarsgård’s face comforted me. Like deer in the headlights the three of us were. Benny and Björn [of Abba] were there, holding our hands. It was criminal how much fun we had on that. It had such a lovely heartbeat of sincerity and storytelling.

Q: You have collaborated with loved ones on films before. For example, November Man IS so different and incredible in its own way. Will you continue to do so?

A: Yes. My [producing] partner, bless her heart, passed away. That’s been a big hole in my heart, losing Beau Marie St. Clair. My wife and I have joined forces and we’re going to do [production house] Irish DreamTime and carry it on. It has to be done. She’s just finished her first documentary called Poisoning Paradise. It’s about GMOs and pesticides in Hawaii. We’ve made that and have another in the cards.

Q: In The Son, Eli McCullough is fixated on how the next generation, as he calls it, “is pure potential—unlit dynamite.” Are there any actors, artists or activists today that you see as symbols of change?

A: It’s an unsettling time. The resistance will certainly grow. The word “resistance” will be used more. It has to be. The pendulum of history has not swung so far into the right…Kerry Marshall is a brilliant painter. To see his exhibit recently in New York was invigorating. The pain and suffering of the community of the black man, woman, and child that he rendered so beautifully on these big, raw canvases…they are in this unreal setting of Americana. It reminds me that as the Trump presidency goes on, there will be a transcendency of power and culture and vision from the music scene, the art world that will find a voice and give hope to us all.