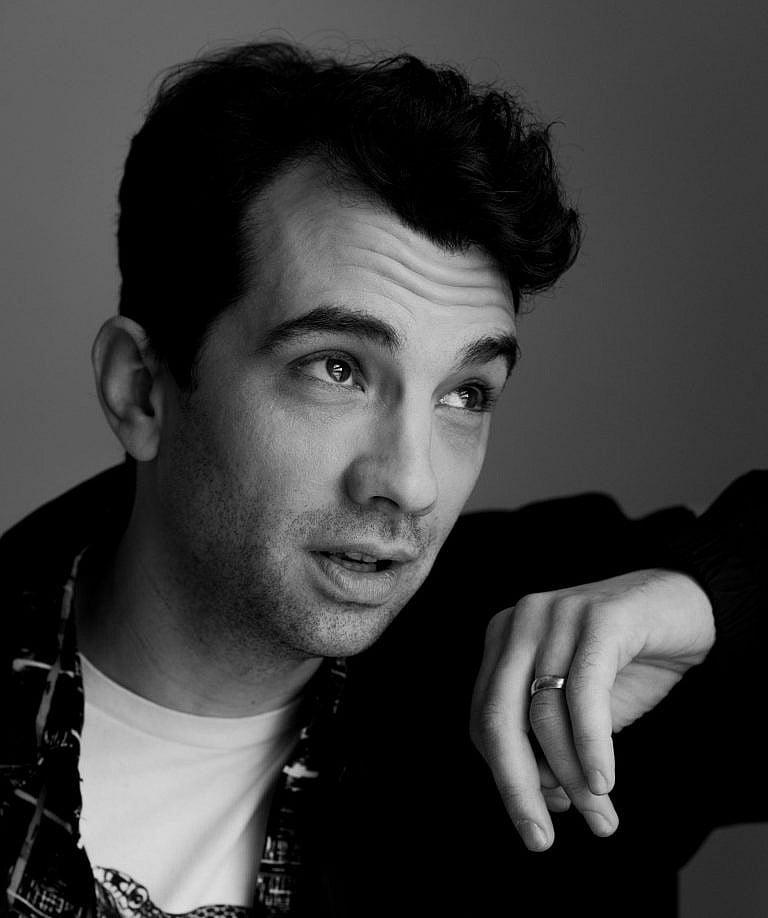

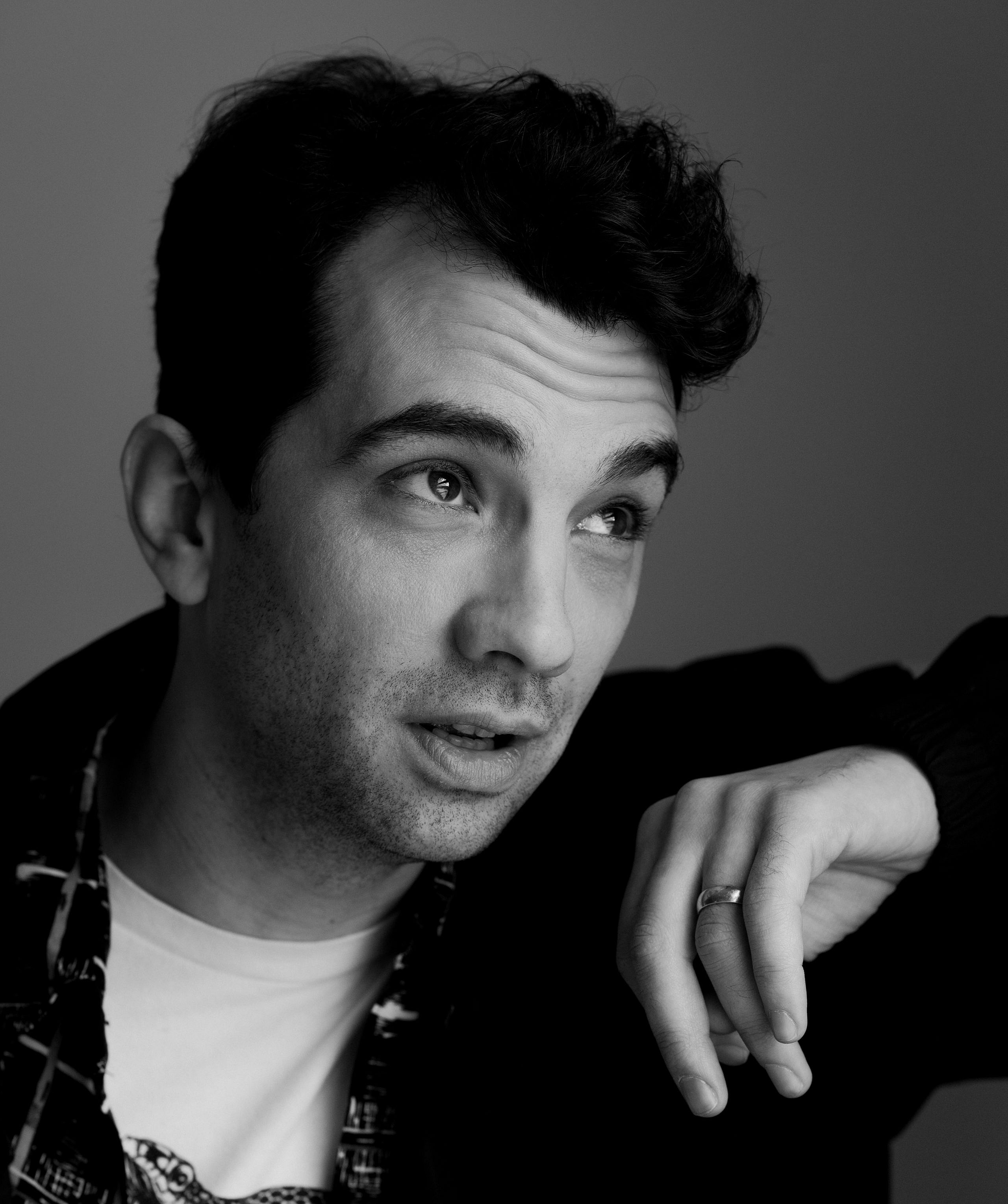

Q&A: BlackBerry’s Jay Baruchel loves movies, weed and his now-obsolete phone

The Montreal native’s latest film chronicles one of the country’s most epic business success stories. Baruchel’s own life story is the stuff of cinema, too.

Share

Jay Baruchel is everywhere: in slashers, sex farces and sports movies; opposite mythical lizards in Disney’s How to Train Your Dragon franchise; and he’s worked with directors as varied as David Cronenberg, Judd Apatow and even himself. If you’re wondering how an Ottawa-born, Montreal-raised kid with a Gumby body and a voice like a twisted balloon has been working steadily since 1995 (he’s now 40 and busier than ever), the answer is simple: Jay Baruchel loves movies—loves them.

Baruchel loved his BlackBerry, too. He hung on to it until 2019. It makes sense, then, that his next movie is, well, BlackBerry. The film, out this month, chronicles the rise and fall of Research in Motion, the Waterloo moonshot whose founders had the zany idea to merge computers with cellphones. Baruchel plays Mike Lazaridis, the engineering student turned RIM co-founder who watched his dreams get gobbled up by the iPhone, but not before they made him a billionaire. Playing the more level-headed partner gives Baruchel a chance to showcase his dramatic chops. It also demonstrates why, unlike the now-obsolete gadget, his success continues.

It’s rare for someone who’s made it in Hollywood to be as proudly Canadian as you.

It’s a function of Canadianness to second guess ourselves, but I was raised to believe this is the best country in the world, warts and all. Part of it is that my maternal granddad was a career soldier, and I have cousins and uncles who are, too. I hope that, one day, it’s not so rare for Canadians who love movies to make them here.

What interested you most about the BlackBerry story?

It’s a definitively Canadian story, something we can claim. It’s also a road map to how we got to this—let’s be honest—loathsome modern world we live in. It’s Canadian in another way, too, in that a lot of people don’t realize BlackBerry is Canadian.

Have you heard from any of the real-life RIM figures?

Not yet, even though we shot in Waterloo, where it all happened. I’m interested to see what those guys think—RIM’s co-CEO Jim Balsillie in particular, given his temperament.

. . . which, in the film, is fractious. Yours, however, is collaborative. You act, write screenplays and direct. When did you first have artistic ambitions?

I don’t remember not having them. My first word was a sentence, a slogan from a 1982 commercial: “Come on, Canada! Meet you at the Bay!” When I was seven, my mom filmed me saying, “I want to write stories that scare Stephen King out of his underwear.” At nine, I realized: No, I want to make movies. So, from 1991 on, that’s been my defining ambition. That, and being as good a person as I can be.

Were your parents artistic?

They were huge movie and TV nerds. We didn’t have a ton of money, so we didn’t go to the cinema a lot. But every weekend, my dad would rent two movies. If they were still in the VCR the next morning, I was allowed to watch them. If they were back in the case, my parents had deemed them too racy. And when I watched something with them, it was Film 101. They paused Monty Python and the Holy Grail 100 times to explain to me why what had just happened was funny.

I read somewhere that your father worked as an antiques dealer.

Antiques dealer, hah! That’s the simplest way to describe him. In the 1970s, he was a drug dealer who went to prison. When he got out, he sold antiques as his legit, going-straight job.

Whoa. Was he a drug dealer before or after you were born?

They overlapped.

How did that affect you?

In a profound way. Dad was a hard dude. He lived to get into fist fights, and he always had a buzz on. Most people had no idea. I can’t say, “I am this specific way because of that.” I just know you take that shit with you.

Did that feel scary?

The opposite: safe as hell. It was only after my parents divorced—and Dad was out of the house—that I felt fear for the first time. When I hit 14 or 15, he became a source of embarrassment. But now, I’m super-proud that I have some of Dad in me. If you have the gawky mannerisms I do—and if, like me, you’re a keener who’s always polite—people mistake those things for weakness. I channel my dad in those moments.

Which moments?

Every audition, and every time someone tried to muscle me. My father would’ve burned the whole city down before he let anybody fuck with me.

You’ve played your share of awkward sidekicks, as in Almost Famous and Knocked Up. How did you avoid being pigeonholed?

I’m reverent of the craft, but I’d be lying if I said I think about acting all the time. I think about stories I want to tell, and scenes I want to direct.

Did directing feel like you thought it would?

I was more assured than I thought I would be. As an actor, I’ve suffered far too many directors who were mushing through fog. I never wanted anyone on my set to not know what the hell we were doing.

What’s your director superpower?

I have a vibe: I want filming to feel as close to a backyard game of cops and robbers as possible—like when you were a kid, making up stories with your friends, fully committed. Filmmaking is the greatest job in the world; it should never feel miserable. You know your favourite movie moments? We’re in the business of creating them. What a cool thing.

Clint Eastwood directed you (playing a wannabe boxer) in Million Dollar Baby. What was that like?

I was scared shitless. Eastwood is the only guy I’ve worked with who my granddad would have been remotely impressed by. At that time, I had a masochistic approach to acting. I had to suffer to be good. I’d ask Clint after every take, “Was that all right?” and he’d say, “It was fine.” In my head, I’d hear, “He hates me!”

Well, did he?

Morgan Freeman saw me freaking out and said, “If he doesn’t say anything, it means he likes it.” I can’t overstate what an epiphany that was. As an actor, you’re always trying to get quote-unquote there. Well, there doesn’t actually exist. From that point on, I could show up on set and not torture myself.

Who else taught you something important?

Cameron Crowe on the set of Almost Famous, the first movie I made in the States. He took time out of his day to play frisbee with me in the parking lot. I was an awkward grade 11 kid from Montreal, and he’d talk to me about Billy Wilder and Alfred Hitchcock. Now, he’s like an uncle I hear from every year or two.

Let’s talk about screenwriting. Does that come easily to you?

I’m spoiled because the first thing I got paid to write—Goon—was a thing everyone loved. It just flowed. Evan Goldberg and I came up with the initial idea in about 10 minutes, on a phone call. I wrote the first pass in two weeks. And it was number one in English Canada, nominated for awards. So, in that one case, screenwriting felt exactly how I hoped it would.

We know from Goon that you’re a hockey fanatic. Tell me everything you love about it in one minute.

It’s the most beautiful and most brutal game in the world. You’ve got huge guys moving at very high speeds, yet it all comes down to millimetre shifts in the wrist. And the gap between observation, decision and execution is a second. It’s like watching a comic book come to life.

Alright, you’ve earned another minute.

I’m going to get super hokey: it’s ours. Hockey is one area where Canadians are sure-footed and definitively proud of who we are. We know this is our gift to the world. It’s an art form we’ve created and exported across the world. We’re so scared of becoming anything close to American in terms of ambition or lauding ourselves—except in hockey.

You also host Highly Legal (a podcast about marijuana) and We’re All Gonna Die, (Even Jay Baruchel), a docuseries about existential threats like climate change. Are these projects opportunities to expand your reach?

I’m in my Michael Palin travel-doc era. If, because I swore a bunch in Goon, or had a semen stain on my pants in She’s Out of My League, I can drive audiences toward stuff I care about, that’s a cool thing.

So legalized marijuana is a subject that’s dear to your heart?

Whatever gave you that impression? Yes. I’m normally a rule follower. In my younger days, I found myself consorting with characters I’d never have had anything to do with if I didn’t have to buy weed from them. So, when the clock struck 12:01 on October 17, 2018, I went onto the Ontario Cannabis Store’s website. By 12:02, I was checking out.

Let’s finish with a big question. What have you learned about people or yourself from all those films?

Not much is sacred in the 21st century. Sincere love between people—romantic, familial, platonic—is one sacred thing. The only other, in my heart of hearts, is the relationship between artist and audience. All I want is to fall head over heels in love with the book I’m reading, the movie I’m watching or the song I’m listening to. I want to think I’ve learned everything I can, then have something blow my head wide open. If I can create half of that experience for someone else, that’s a life worth living. I don’t hate-watch or hate-read. What a silly waste of time.