The Greatest Gatsby ever sold

Jessica Allen on the orgy of merchandising for a film based on the loneliest book ever written

Warner Bros. Pictures

Share

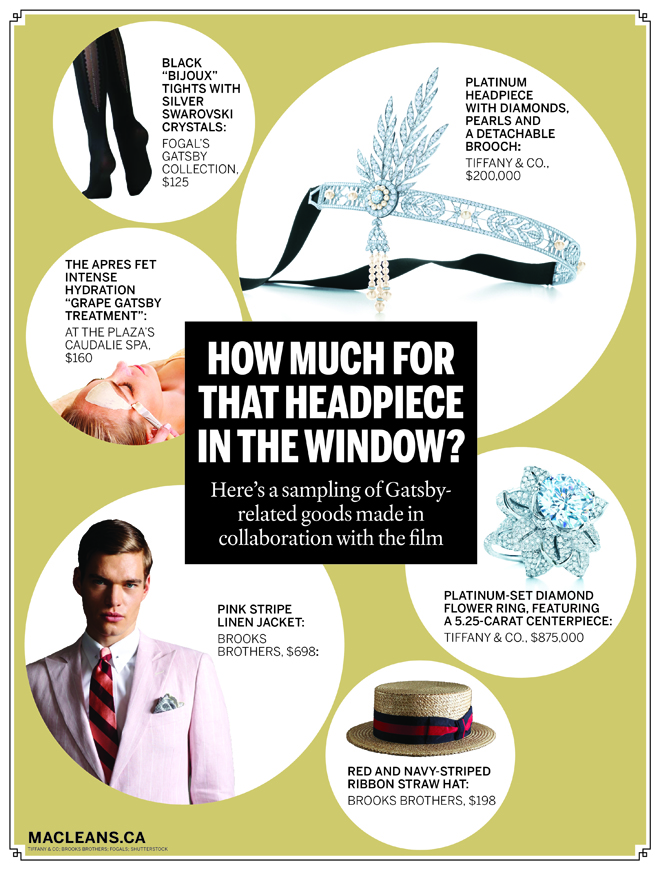

Turn on a television, pass a shop window or a bus shelter these days, and you are engulfed by the opulence of the Roaring Twenties, the bold, clean angles of art deco design, and the jauntily attired figures of Leonardo DiCaprio and Carey Mulligan—the stars of Baz Luhrmann’s film adaptation of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s third novel. If The Great Gatsby ever went away, it’s unavoidably back. It’s now the fourth-bestselling book on Amazon, 88 years after it was first published. And the film’s partnerships with Tiffany & Co., Brooks Brothers and Moët & Chandon hope to resurrect other Jazz Age gestures: two-toned brogues, bow ties, a 5.25-carat flower-shaped diamond ring (price tag $875,000).

The film, which opens May 10, promises to be an over-the-top hyperactive kaleidoscope of colours, with a hip-hop-infused soundtrack produced by Jay-Z—all in 3D, and none more so than the merchandizing collaborations, which we’re told all make sense. “[Fitzgerald] went to Brooks Brothers and Tiffany, which was of course the jeweller of the Jazz Age, and drank Moët,” fashion editor Marion Hume told the Australian Financial Review. The Plaza Hotel in New York, the setting for a climactic scene in the novel, has also capitalized on Gatsby’s popularity. For about $2,800, guests can book a night in the Fitzgerald Suite, have the “Moët Imperial Gatsby” champagne cocktail in the hotel’s Rose Club, or enjoy “Caudalie Grape Gatsby Treatments” at the Plaza’s spa.

That’s a great deal of hoopla for what many consider to be one of the loneliest books ever written: it may be filled with revellers, but they’re all strangers. The aloneness is best exemplified by its protagonist, Nick Carraway, the Midwesterner who comes east and finds himself a secondary character in the drama of his own life, and of the figure of Jay Gatsby himself, who desires to create a moment of affection from his past while hiding his working-class origins. It’s also a lot of expensive stuff hitched to a story that is in part about what money can’t buy.

Harold Bloom, author of The Western Canon (among many other books) and editor of numerous essays on the novel, agrees. He won’t be seeing The Great Gatsby. (Nor did he see Luhrmann’s 1996 adaptation of Romeo and Juliet, even though its star, Claire Danes, was a student of his at Yale.) “Very rarely is the film an improvement on the book,” the 82-year-old told Maclean’s. He first read Gatsby when he was 12 or 13 and has since returned to it about eight times.

And rarely outside the Disney franchise does a film generate such materialistic infatuation long before it is released: the New York Times recently reported on the steady upswing of 1920s-inspired wedding-dress sales; a Great Gatsby search on the craft shopping site Etsy yields more than 4,250 results; and an eBay representative told the blog Fashionista that, in the past year, there has been more than a 530 per cent increase in sales of Gatsby-related women’s clothing items. That’s a lot of headpieces.

On the other hand, the exposure could help reinvigorate interest. After Anne Margaret Daniel, a professor of literature at the New School in New York, saw a recent preview of Luhrmann’s film, she overheard a group of students discussing, not the movie, but the book—and the location of the closest Barnes & Noble. “I was cheering inside,” she said. “It’s a book that people haven’t come back to in 30 years, and now they’re going to reread it. Hats off to Baz Luhrmann for that.”

It’s a fitting tribute, in a way, to a man who turned to screenplays in his late 30s to make money. Daniel is writing a book on Fitzgerald’s time in Hollywood and she thought Luhrmann’s film was brilliant. “Don’t judge a film by its trailers,” she warned. “It doesn’t just bombard your senses. It exercises them.”

It’s hard to know what the author would have thought of all this. But Daniel came across a letter from 1927 in the Princeton library archives, where she received her Ph.D.—and where Fitzgerald dropped out to join the army—written by Zelda Fitzgerald to the couple’s then six-year-old daughter, Scottie: “We saw The Great Gatsby in the movies,” she wrote of the now-lost silent-film version. “It’s ROTTEN and awful and terrible and we left.”