Who’s the ‘slick fraudster’—the man claiming he’s an MIA or the U.S. military?

An MIA’s family will contribute DNA to prove the man lost to the jungles of Vietnam is their kin

Share

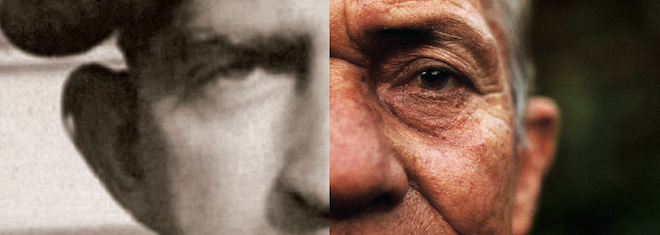

As expected, the April 30 Hot Docs world premiere of Unclaimed—a Canadian documentary about a man emerging from the Vietnamese jungle claiming to be a U.S. soldier given up for dead in 1968—has ignited a firestorm of media controversy. In a Maclean’s story last week, I explored the film in detail, and conducted the first media interview given by Alabama’s Gail Metcalf, the niece of MIA John Hartley Robertson, and his family’s official spokesperson. After a cathartic reunion with the self-proclaimed MIA in Edmonton, which stretched over five days, Metcalf and her family—including Robertson’s sole surviving sibling, Jean Robertson Holley—were utterly convinced the man is their “Johnny.” Meanwhile, the movie’s Alberta director, Michael Jorgensen, has had dealings with the the U.S. military that point to a possible cover-up. He said he met with one official who lied to him that Robertson’s brother (now deceased) and his sister, Jean, had cooperated with the military and provided DNA—which the family denied.

Immediately after news reports of the film’s sensational discovery went zinging around the globe, came an equally sensational backlash—a rash of headlines declaring that the man claiming to be Robertson was in fact a “slick fraudster” whose “hoax” had already been uncovered by the U.S. military. The news originated from a U.S. military memo that was fed to the U.K.’s Daily Mail website. According to a 2009 memo from the Defense Prisoner of War Missing Personnel Office (DPMO) that surfacedMailOnline, the man, Dang Tan Ngoc, came to the attention of U.S. personnel in Vietnam in 2006, claiming to be Sgt. John Hartley Robertson, reported killed in action during a special forces mission over Laos in 1968. The memo states that, under questioning, the man admitted that he was not Robertson, but that he tried to pose as him again in 2008, and was fingerprinted at the U.S. Embassy in Phnom Penh—and that the FBI reported his prints did not match those in JHR’s records.

The memo states: “In 2009, the Vietnamese man was interviewed again by U.S. officials, who collected fingerprints and hair samples for analysis. The FBI analyzed the fingerprints and they were determined not to match Robertson’s fingerprints on file. The mitochondrial DNA sequences from the hair samples obtained were compared to family reference samples taken from Robertson’s brother and one of his sisters. The Armed Forces DNA Identification Laboratory (AFDIL) determined the DNA sequences from the Vietnamese man did not match either of Robertson’s siblings.”

This report, which never reached Robertson’s family, contradicts their version of events. In an interview, Jorgensen told me the family—who say they require no proof for themselves—will provide DNA samples to convince a skeptical world that have indeed found their missing relative and to draw attention to the Pentagon’s failure to communicate with relatives of MIAs. The filmmaker, meanwhile, says the U.S. military has lied before about the Robertson case. He said an official from its Joint Personnel Recovery Agency (JPRA) told him Robertson’s brother (now deceased) and sister had already provided DNA, when in fact the sister maintains they’ve not been approached by the military and have never contributed DNA.

Jorgensen also points out that if what the memo says is true, standard operating procedure requires the military to inform the family about any reports of someone claiming to be a lost MIA relative, even if they are false. According to Metcalf, her family received not a single report of men falsely claiming to be Robertson until last March, when she went to a Department of Defense briefing for family members of POWs/MIAs in Birmingham and was given a report with an account of some 30 false claims, including mentions of Dang Tan Ngoc, but there was no reference to the DPMO’s 2009 analysis of his fingerprints and DNA.

Finally, if this 74-year-old enigma is a scam artist, it’s one strange scam. “A scam implies you’re out to get something,” Jorgensen told me. “Here’s a guy who, by his own family’s admission, has never asked for a thing. His only wish was to see his sister before he dies. She said to him ‘What do you need? Do you need money?’ And he said, ‘Nothing. I just wanted to see my family one last time.’ ”

Having spent a lot of time with Ngoc/Robertson, the filmmaker adds, “I don’t think he’s capable of perpetuating a scam.” And anyone who has seen the documentary would likely concur. If he’s a scam artist, one with the apparent motive, he deserves an Academy Award. “I don’t need to be convinced one way or the other,” says Jorgensen. “But I believe the circumstantial evidence strongly indicates this man is John Hartley Robertson. What’s perplexing to me, if this guy’s a fraud, and is not Robertson, there’s a guy living in Vietnam who looks very much like him, and knows things about his family that no one could possibly know. So who is this guy?” Not to mention the fact that the man was willing to have his last molar extracted by a Vietnamese dentist, allowing a lab back in the U.S. to do isotope tests, which proved conclusively that he grew up America.

Given the family’s concern, and the serious allegations that have been made, it seems the onus is now on the Pentagon to explain itself, beyond the scope of a 2009 memo that has surfaced in a British tabloid. At the very least, it’s puzzling why Robertson’s family has been kept in the dark.

For the record, before publishing my original story, I requested an interview with an official from the JPRA. After several days, I received a blanket denial of Jorgensen’s allegations via a Dept. of Defense spokesperson, but was unable to talk to anyone from the JPRA, or anyone with first-hand knowledge of the case.

Despite what the latest round of headlines claim, this story is far from over.