Netflix’s secret weapon against Disney

John Semley: The entertainment giant wants to compete with Netflix. But the miracle-making streaming service knows what its customers want—even before they do.

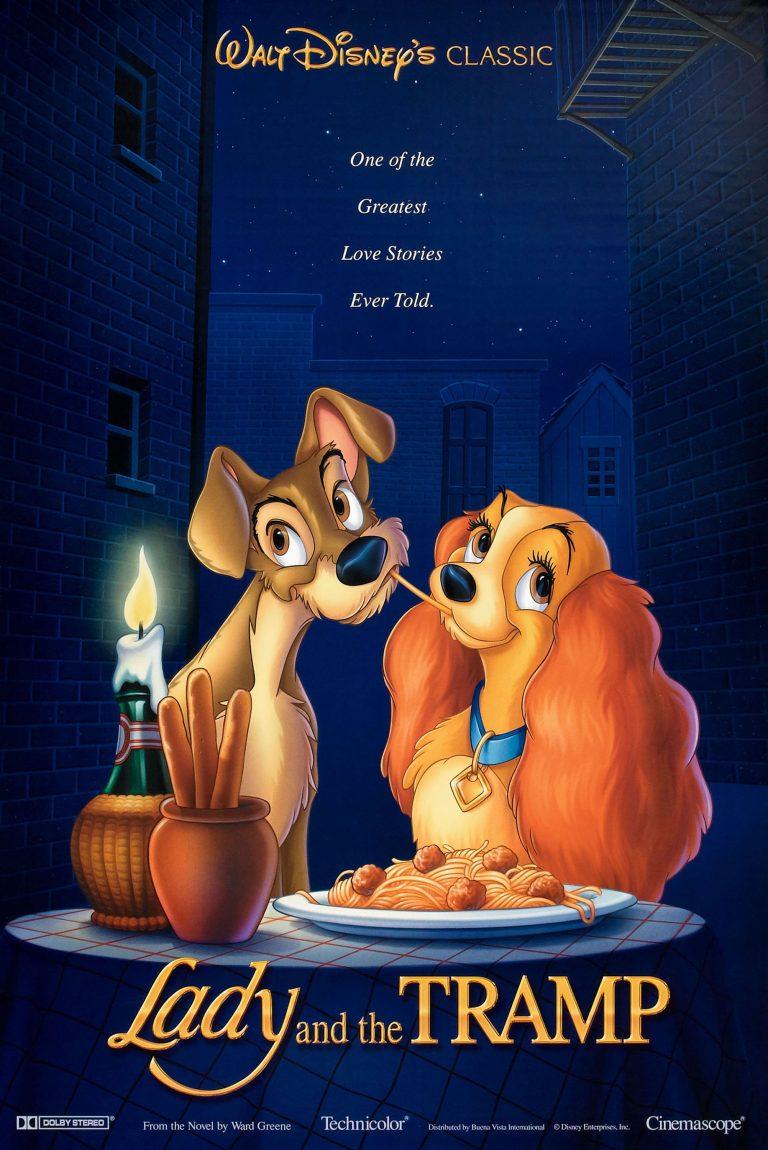

Fans of canine romcoms can look forward to Disney’s remake of ‘Lady and the Tramp’ (Everett Collection)

Share

On Nov. 2, 2018, streaming media giant Netflix premiered a remarkable piece of original content. Not the science education series Brainchild, or the latest season of the animated kiddie series Trolls: The Beat Goes On!, or even the final, Kevin Spacey-less season of the hit political drama House of Cards. The appointment viewing that weekend was The Other Side of the Wind: the long-languishing final film from director Orson Welles, the visionary innovator behind classics like Touch of Evil, The Magnificent Ambersons and, most notably, Citizen Kane.

Serious cinephiles and film historians regarded the unfinished The Other Side of the Wind as a cinematic lost ark. Started in 1970, the film fell victim to countless production trip-ups. Regardless of what one makes of the finally completed film itself, simply seeing it—at home, preceded by the da-DOMP Netflix logo—was remarkable. The company that began in 1998 as a modest mail-order DVD rental outfit is no longer merely a global entertainment company. Netflix can now make miracles.

READ MORE: Netflix and shill: What the Liberals’ big announcement adds up to

If any other media giant can cut into Netflix’s status as miracle-making media behemoth, it’s the Walt Disney Company. Long purveyors of cinematic magic, pockets deep with pixie dust, Disney is moving into the streaming media game, cutting ties with Netflix by the end of this year and launching its own competing service in 2019.

The nitty-gritty details of Disney Plus, as the service will be known, have yet to materialize. But while we don’t know how it will compete on price or streaming quality, what Disney does have in its favour is its brand. Or, rather, brands. Fans of mega-franchises like Star Wars and Marvel and High School Musical are likely to sign up for the new service, which will house not only existing titles, but entirely new offerings. There will be a new live-action Star Wars series developed by director Jon Favreau, a show starring Avengers villain Loki, and remakes of Disney classics like The Sword in the Stone and Lady and the Tramp. Netflix thrives, in part, on the sheer breadth of its catalogue; Disney’s platform will focus, according to CEO Bob Iger, on “high quality.”

It’s a tantalizing play for both movie fans and market speculators. Disney-owned brands dominate the global box office. And Disney’s acquisition of 21st Century Fox also gives it access to other fan-favourite franchises, such as The Simpsons and the X-Men. Anyone interested in mega-franchises will find some allure in Disney’s at-home service.

Of course, Netflix has now built its own stable of exclusive properties—Stranger Things, BoJack Horseman, Big Mouth, Orange Is the New Black—while also luring top-shelf cinematic talents. Beyond Welles’s long-lost holy grail, Netflix also boasts original films from the Coen brothers (The Ballad of Buster Scruggs), Noah Baumbach (The Meyerowitz Stories), acclaimed South Korean import Bong Joon-ho (Okja) and the forthcoming Martin Scorsese crime drama The Irishman. Sure, Netflix also churns out plenty of dross. But it’s hard to deny that the company has become a credible creative engine that bankrolls prestigious work.

The Netflix brand is now about more than its individual films and franchises. It’s synonymous with streaming films and TV shows at home. Just as one may ask for a “Kleenex” rather than a “sanitary tissue,” one invites another over to “Netflix and chill,” not “Disney Plus and chill.” The hegemonic hold Netflix exerts over not just the business but the very experience of streaming content at home is demonstrated by the recent shuttering of rivals like FilmStruck and the repackaging of Bell Canada’s CraveTV service.

And Netflix has something even brawnier than the combined powers of the X-Men, the Avengers and the Guardians of the Galaxy. It has its algorithm. As a group of Netflix developers explained in a 2017 Medium post, “With a catalogue spanning thousands of titles and a diverse member base spanning over a hundred million accounts, recommending the titles that are just right for each member is crucial.” These formulas are so complicated that they can even adjust the artwork displayed for a certain title in order to better lure potential viewers based on their habits. Someone who watches a lot of romantic comedies will see Good Will Hunting advertised with an image of Matt Damon and Minnie Driver, whereas a comedy fan is more likely to see the same movie promoted with an accompanying still of a beaming Robin Williams.

For better or worse, Netflix has effectively supplanted the video store clerk who helpfully suggests titles based on your rental history, with a carefully calibrated formula for keeping viewers locked to their screens. And what’s more, it has used this data to develop its own original content, from the gloomy House of Cards to a slate of Adam Sandler vehicles. Viewers might know Captain America or Olaf or Princess Leia or any of the other Disney-stabled characters. But Netflix knows its users—and gives them what they want before they know they want it. It’s one thing to satisfy a desire for a specific type of programming, as Disney intends to do. But satisfying desires that viewers aren’t even aware of requires considerably more cunning.

Of course, the Disney vs. Netflix melee is not a zero-sum game. Viewers (and investors) can buy into both and enjoy their relative merits without it being some winner-take-all bloodbath. With its cache of name brands and longer history of global entertainment domination, Disney offers the stability of a legacy corporation. Netflix, with its astounding growth and its wily algorithm, undoubtedly serves up something even more exciting to both the at-home viewer and the adventurous shareholder: the potential of the future.