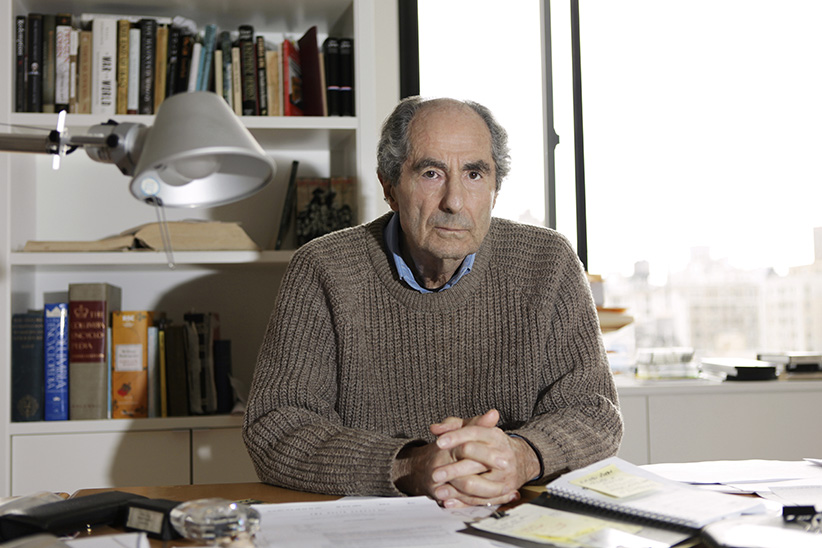

Philip Roth and why good books make bad movies

The latest attempt to translate Philip Roth shows the challenge with adapting literature to film

Logan Lerman, and Sarah Gadon in Indignation. (Alison Cohen Rosa/Roadside Attractions/Everett Collection)

Share

Philip Roth is one of North America’s most acclaimed writers, and also one of its most unsuccessfully filmed writers. So far 2016 has brought not one but two movie adaptations of novels by the 83 year-old Roth, and neither one has threatened to upstage the hardcover versions. After Indignation, which got respectful reviews but did little box-office business, comes American Pastoral, which opens in wide release later this month after a run at the Toronto International Film Festival. Based on Roth’s Pulitzer prize-winning book about the turmoil of the 1960s, the directing debut for actor Ewan McGregor has drawn mostly negative reviews—a hit, it seems, is not on the horizon.

But if American Pastoral doesn’t do justice to the novel, it will be in very good company. Serious novels—or at least, ambitious novels—are hard to make into movies. Yet movie people keep trying.

“Most of the movie adaptations of Roth’s books have been disappointing—to say the least,” says David Brauner, professor of contemporary literature at the University of Reading and co-editor of the journal Philip Roth Studies. The only really successful Roth adaptation was a film of his early story Goodbye, Columbus. But since then we’ve had productions like Portnoy’s Complaint, based on his most famous novel and one of the most disastrous failures of the 1970s, or The Human Stain, which is now mostly remembered for the infamous miscasting of Anthony Hopkins as a black man pretending to be Jewish.

There have been so many unsatisfying movie versions of Roth novels that there’s a small cottage industry in think pieces telling Hollywood to stop trying. This year alone The New Yorker offered “Philip Roth versus the movies,” while the prestigious Paris Review titled an article “It is very, very, very hard to adapt a Philip Roth novel.” The entertainment site CHUD once announced a Roth movie with the headline, “Unadaptable novelist adapted again.”

But then, it’s hard to adapt almost any modern work that falls into the category of literary fiction—the kind of book that wins Pulitzer and Booker prizes, rather than being sold in airports. Jonathan Franzen (The Corrections) has been announced for multiple film and TV projects that don’t get made. Superstar producer Scott Rudin (Clueless, True Grit) bought The Corrections and spent years trying to film it, resulting only in a television pilot that HBO turned down. Susan Orlean’s non-fiction book The Orchid Thief was so hard to make into a movie that screenwriter Charlie Kaufman wrote an entire film, Adaptation, about the story of his failed attempts to turn it into a workable script.

It’s not hard to see why well-regarded modern novelists, or even non-fiction writers, aren’t naturals for the movies. Like many prize-winning novelists since the 1960s, Roth is less focused on telling stories than analyzing his reactions to them, often weaving in details of his life or appearing as a character under the name of Nathan Zuckerman. “Roth remains especially difficult partially because so much of his fiction is devoted to charting the development of the inner life,” says Matthew Shipe, a lecturer in advanced writing at Washington University in St. Louis and president of the Philip Roth Society. “Roth’s novels rarely rely on traditional plots that could be easily translated into a film.” Even a book like American Pastoral, which deals with crime and terrorism, doesn’t foreground those themes.

And because modern literary fiction is partly a reaction against the movies, an attempt to do things on the page that can’t be replicated in film, novelists like Roth fill their books with devices that aren’t meant to translate to any other form. “What makes Roth a great novelist, above all else,” Brauner says, “is not his plotting or characterization—things that are reasonably transferable to the film genre—but his narrative voice, which is not.”

Shipe adds that a book like American Pastoral is only partly about the story it tells, and partly about how “Nathan Zuckerman reconstructs other people’s lives from his own partial knowledge of the facts—this frame is vital to those novels’ meanings, and it is hard to imagine translating that narrative frame into a film.” Novels in an older tradition are relatively easy to adapt for film and TV, because they depend on action, dialogue, and realistic details that a movie can recreate. But if you take away the author’s voice from a lot of modern novels, you may be left with a story that is too thin for a mainstream movie.

Months before it was published, Indignation, about a 1950s college student very much like Philip Roth, was optioned by Scott Rudin for what Variety described as “a seven-figure deal.” He was chided by Portfolio journalist Lauren Lipton for paying that much money “given Roth’s Hollywood track record.” The movie was never made.

Hollywood producers, in spite of their reputation for crassness, often have a love of good literature and a desire to translate it to film. In addition, literary adaptations, no matter how hard they are to get right, may actually be less risky than other types of serious moviemaking. This is an era where studios are often reluctant to commit themselves to movies that don’t have a well-known brand behind them, and that applies to an Oscar-bait movie just as much as Star Wars or Ghostbusters.

“I’m doing a lot of adapting,” Rudin told Indie Wire in 2010, explaining why so many of his projects were based on well-known books; he added that selling a movie to a major studio is “harder than it’s ever been,” which means that it helps to have a familiar property to sell. A well-known, prize-winning novel can allow movie creators to get their foot in the door with difficult subjects; an original script, even if it’s more cinematic, might be turned down.

But sometimes a filmmaker comes along who knows what to do with these properties. Ang Lee is one director who draws much of his Hollywood success from adapting literary fiction. He won his second Best Director Academy Award for a well-regarded adaptation of Yann Martel’s Booker prize-winning novel Life of Pi, which was heavy on philosophy and light on plot, while he won his first Oscar for a film of Annie Proulx’s melancholy short story Brokeback Mountain. Unlike most of the movie directors who have taken on Philip Roth novels, Lee has been able to use atmospheric, dramatic effects to make up for the lack of the prose on the page.

It’s also hard to argue that any novel is unadaptable, when even the most complicated literary devices can be cracked for the screen by the right writer. The Criterion Collection recently released a Blu-Ray of the 1981 film version of John Fowles’ complicated literary conceit The French Lieutenant’s Woman, where half of the book was about the narrator’s indecisiveness about the story he was supposed to be telling. Screenwriter Harold Pinter threw out this aspect of the story and replaced it with a new plot about two actors making a film of the book’s story. The most challenging fiction can become a movie if the filmmakers don’t treat the material with too much reverence.

Or the novel could be turned into a TV series instead. Serialized television, with its ability to let stories unfold slowly and scenes play out longer than they would in a film, is often a better home for ambitious fiction; a show like Mad Men has a lot in common with modern theme-laden novels. Accordingly, some producers are already trying to shop serious novels to television networks and outlets.

Already this year, undeterred by the problems with The Correction, Rudin announced plans to turn Franzen’s novel Purity into a 20-part series starring James Bond actor Daniel Craig; telling the story over 20 hours might allow more of Franzen’s idiosyncracies to survive than they would in a feature film. And in June of this year, writer-actor-director Sarah Polley announced plans to turn Margaret Atwood’s Alias Grace into a series that will be a co-production by Netflix and the CBC. Atwood hasn’t had much luck on film so far—witness the unsuccessful 1990 movie based on her dystopian novel The Handmaid’s Tale.

Many successful filmmakers have shied away from literary masterpieces and stuck to stories that don’t have to be approached reverently, like detective mysteries and westerns. Two weeks before McGregor releases his struggle with American Pastoral, Ron Howard will release Inferno, his latest adaptation of Dan Brown’s Da Vinci Code thrillers. No one will mistake it for a Booker prize-winner—but sometimes bad books make more popular movies than good ones.