Q&A: Ken Dryden on the Summit Series 50 years later

16 million out of 22 million Canadians tuned in for the final game in the legendary battle between Canada and the USSR

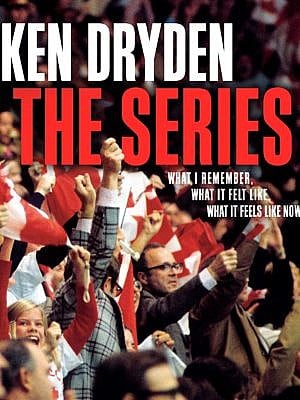

Ken Dryden revisits the Canada-USSR rivalry in his newest book (Photo by Sergei Smirnov)

Share

Ken Dryden, 74, is a lawyer, businessman, author and former federal cabinet minister. But what Canadians most remember him for is his Hall of Fame career in hockey. What Dryden recalls most vividly from his storied goaltending tenure with the Montreal Canadiens is not the six Stanley Cup championships in eight seasons, but his performance in the Summit Series—the iconic eight-game exhibition match up in 1972 between Canada and the Soviet Union which celebrates its 50th anniversary next month. In his latest book, The Series: What I Remember, What It Felt Like, What It Feels Like Now, Dryden delves into his memory to offer a visceral and evocative recapture of an event that riveted Canadians’ attention like little else before or after. He spoke with Maclean’s about the legacy of the series and why it still matters today.

Maclean’s: There is a key statistic you mention more than once in the book: 16 million of 22 million Canadians watched the final game of the Summit Series (on September 28, 1972).

Ken Dryden: That tells the story better than anything for a game that was on during work hours and school hours. Every hockey fan has their favourite memories—could be the 1987 Canada Cup with both Gretzky and Lemieux, or the 2010 Olympics in Vancouver. So my challenge was, how do you get somebody who has other reference points to understand the 1972 series actually was different for Canadians? The only way that I could think of was to put them right into the moment. This wasn’t going to be a book where I interview players, go online, do all kinds of other research. No, it’s either in me or it isn’t in me.

You simply pulled this from your memory as best you could?

Yes. When I finally decided to do it—I had been asked many times before, 25th anniversary 40th anniversary—it was almost a writing frenzy. Within three weeks I was at the end, but I didn’t really know what the end was.

Do you mean that after going through the first parts of the subtitle—What I Remember, What It Felt Like—you were uncertain about the third, What It Feels Like Now? Did writing the book change your thoughts, your memories?

The act of writing means discovering something all the time, that’s why you do it. Until the end, I was trying to put my finger on why it mattered so, until I got to this: the experience was so utterly personal for the players stepping onto the ice in Montreal on Sept. 2, 1972. My story starts with the Penticton Vees winning the world championship in 1955 when I was seven and then the Russian domination of international hockey that began in 1963.

Phil Esposito would have another story, and Paul Henderson another still. But they were the same essentially. We were the originators of hockey, the world’s best. That’s why 16 of 22 million watched, because we had to prove it and because it was personal for the fans, too. That’s why 3,000 Canadians showed up in Moscow, when Canadians weren’t big travellers—sure as heck not to the Soviet Union.

I thought you captured the Canadians abroad quite well, partly because you sat among them when Tony Esposito was in goal. They had a feeling about hockey and a feeling about being Canadian, and an indefinable feeling those two things were intertwined.

That’s right. I think that is what it was, just so utterly personal for us all.

Your greatest regret was that, as part of the team, you were not part of the national experience?

Exactly! I would’ve loved being in Montreal watching the series. I would’ve gone nuts watching. We players each had our own go-nuts experience, but none of us had all of it.

Despite your participation, you often didn’t have a very good perch—when Paul Henderson scored the most famous goal in Canadian history, winning the series 34 seconds before the buzzer, you were 180 feet away.

I remember the red light or Henderson’s stick in the air, I don’t know which came first. I remember being at centre ice—I don’t remember how I got there—my whoops and hollers. But I didn’t see the goal.

The same goes for the most famous non-game moment in the series when, after the crushing loss in Vancouver, Phil Esposito delivered a defiant speech to angry fans.

We didn’t hear it, we didn’t see it, we were in the dressing room. It had no effect on us, but what I hadn’t thought about before is its very large effect on the Canadian public.

Everything that had led up to it—press and fans on about overpaid, over-privileged, out-of-shape players getting all this money for playing a kid’s game and they don’t care—and, then all of a sudden, Esposito is on the ice doing this interview. And it’s like, holy…this guy cares. Look at his face, look at the sweat pouring down, listen to his words. The eloquence of it, talking back over himself, interrupting himself, reinforcing the emotion of what he was expressing, I think from that point on, the series was much more us-and-us than us-and-them in our relationship with the fans.

You do write about the most controversial moment, when Bobby Clarke delivered a two-handed slash to the Soviets’ most dangerous forward, Valery Kharlamov, fracturing his ankle in game six. But you refuse to pass judgment on it.

Well, I don’t know that any of us know entirely what we will do in certain circumstances under pressure. I just don’t know what I would do.

Did Kharlamov’s hobbling affect the series?

There’s another moment, also in the sixth game, where the puck went past me and right back out in front. Did it go in the net or not? I don’t know. What I do know is that it happened in the second period when we were ahead, and the Russian team did not score in the third period. They had their own fate in their hands, and whether that puck went in or it didn’t go in, they had lots of time to change that game.

Same with Kharlamov. Lots of things happen in hockey. Players get injured, or they go into slumps. It was up to the Soviet team to find an answer if Kharlamov wasn’t able to play, and they didn’t find an answer.

It’s game eight—the decider—and you’re going to be in the net. The day before, when you wake up, your legs feel like jelly, because you know that the day after the game you could wake up the most hated man in Canada. An excruciating wait time for you.

It was. I’m a sports fan. I knew all about Bobby Thomson, who hit the famous “shot heard round the world,” but I also remember Ralph Branca, who threw the pitch that became that home run—and what happened to his career after that. This was going to be the biggest stakes game that had ever been played in hockey. Something like that, usually there’s going to be a hero, and usually there’s going to be a goat. That was what was at stake.

Then Henderson scored, and all was well. You recall a dressing room awash with celebration and “deep relief,” a feeling like being shot at and missed. The series opened up new modes of play for Canadian hockey and gave this country its great sporting opponent.

Having that great opponent is crucial to everything, to your own team’s greatness and to your emotions and memories. What are you going to remember 20, 40 years later? I think there were five or six players from the Montreal Canadiens. We all won piles of Stanley Cups, with most of us playing much more prominent roles than we did in the ‘72 series.

So why is it the absolute favourite, the most vivid memory for us and the other team members and even the Soviet players? How can it be that way for them? They won all kinds of Olympic gold medals and world championships. They won them, they lost this. It goes back to the great opponent. That is what generates the moment and generates the memory, the sustaining memory that lasts.

The Series: What I Remember, What It Felt Like, What It Feels Like Now is available now.