Ranking the top Canadian books of the past 25 years

Award-winning authors and journalists dissect the most influential Canadian books of our times

Share

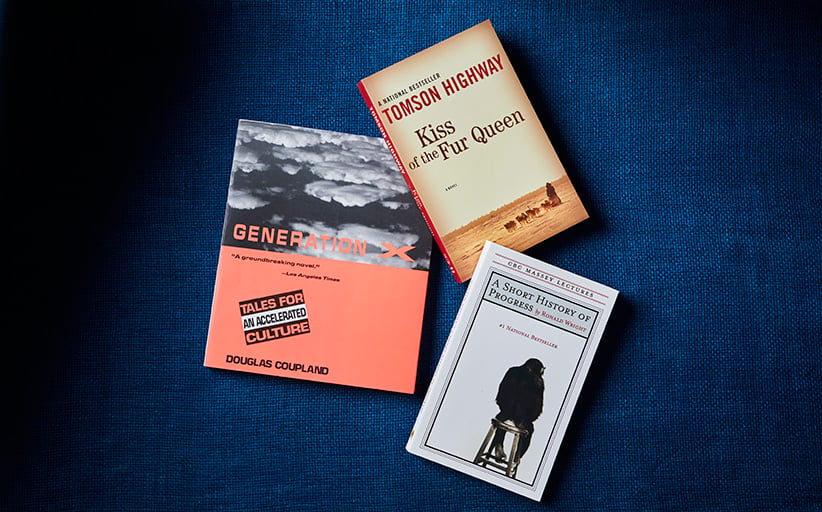

It would seem to be courting controversy to choose from the half million or so books published in this country in the past 25 years a list of the top 25. This week the Literary Review of Canada (LRC) marks its 25th anniversary by doing just that. The magazine’s list of the “25 most influential Canadian books,” along with written defences by prominent Canadians, appears in an editorial supplement in the LRC’s November issue. Herewith an excerpt.

Charles Foran on

A Short History of Progress

by Ronald Wright

Environmental anxieties had already turned apocalyptic by the time A Short History of Progress appeared in 2004. Irrevocable planet abuse, slow and steady and requiring a keen eye to track, had finally supplanted the bright ash of nuclear self-immolation, a grim new species of worry for a new millennium. Even so, 9/11 and the invasion of Iraq deflected attention, in particular during the period when so-called “civilizational conflict” seemed to apply a patina of universality to those events. It could be confusing.

For many Canadians, Ronald Wright’s Massey Lectures helped clear the fog of war to show the true battlefield of our century—the very planet we occupy. Better, the lectures and book laid out the terms of engagement with a startling cross of anthropological dispassion and Old Testament prophecy. Simply, alarmingly, the battle was us vs. us, our rapacious appetites and headlong drive to run our experiments in civilization into the ground.

Rise and fall and rise again? Here was the scary twist to the history-repeating-itself tale. This time around, Wright warned, no one, including the innocent Earth, would get out of the conflict alive. A Short History of Progress first takes the reader by the hand for a walk through the “progress trap” pattern of civilizational history. Then it abruptly releases us into the end-of-pattern trajectory of our current unfolding catastrophe, a possible future of “chaos and collapse that will dwarf all the dark ages of the past.”

If that last phrase—which appears in the second-to-final sentence in the final lecture—does indeed lean more toward Book of Revelation than Book of Argument, so be it. Wright certainly hoped to plant a few seeds of grave concern in the hope they would grow into commonplace ideas. For his popularizing of the “progress trap” alone—a nifty distillation of our fixation on one way of being in the world—the cultural legacy of A Short History of Progress would be secure.

A quiet source of authority for Ronald Wright the historian and anthropologist is Ronald Wright the novelist, most notably author of A Scientific Romance, published in 1997. Novels are the news that stay the news because they tell the story that stays the story. That would be, once again, about us vs. us, and if you believe the tale told in A Scientific Romance—or, for that matter, in David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas or Margaret Atwood’s Oryx & Crake, comrades in the early-new-millennium dystopian fiction cadre—there is no happy ending up ahead.

But A Short History of Progress isn’t the Massey Lecture version of a droning barstool sermon of gloom. Quite the opposite. Wright is much more than a gentleman pessimist. He is erudite and witty, never pompous or boring, and forever inclined to gently encourage rather than just severely scold. Above all, he is a superb writer, clean and crisp and happy to generate sentences with old-fashioned locomotion.

Hardly a surprise that A Short History of Progress was a publishing success. (The copy I recently re-read is a 14th reprinting.) It strikes this reader as the perfect Massey Lecture. The subject is at once urgent and timeless, the themes are broad and serious but not esoteric, and the delivery is confident, accessible and purposeful in its provocations, especially the questions it asks. Most important, the thinking is original and unexpected while unfolding in the challenging “real time” of public performance, of thoughts being crafted to share aloud.

None of these are small achievements. All will ensure the book continues to be read for years, decades—even centuries, should we take that “last chance to get the future right” Ronald Wright offers in his closing sentence.

Adam Sternbergh on

Generation X

by Douglas Coupland

I have a first edition of Generation X, signed by Douglas Coupland. I bought my copy when I was 20, in 1991, when I was in the grips of Couplandmania, like every other twentysomething I knew. My edition is not only signed and dated (Sept. 14, 1991), but it contains an outline of Coupland’s handprint, as well as my own name, Adam, drawn in a little box, meant to resemble an entry on the periodic table. All of this happened at a bookstore in Montreal, where I was then going to college. I remember the evening very well. The crowd was large. Coupland was late. He swanned in—I’m sorry, but that’s the verb that comes to mind—attended by friends, then announced he wouldn’t be reading from his book. Instead he would read a short excerpt by, if memory serves me, Margaret Drabble. Afterward, I was waiting near the front of the line to get my book signed when a woman, who I think was one of Coupland’s friends, asked him jokingly to sign her cleavage, which she then amply presented. He autographed it with a Sharpie. The whole exchange felt to me like a mockery of the entire event. I felt kind of stupid. I remember all this so well because I wanted so badly to be Douglas Coupland. We all did. He had done the thing that every young writer aspires to do. He had written a generation-defining—hell, a generation-naming—novel. He was, quite literally, the voice of his generation.

Becoming the voice of your generation is a kind of curse, both for a writer and a novel. Generation X exists now in cultural amber, more artifact than literature. People rarely ask, “Yes, but how was the writing in Generation X?” for the same reason people rarely ask, “Yes, but how was the music at Woodstock?” But here’s the answer: it’s very good. Generation X is an excellent novel. It exists proudly in the lineage of generation-defining novels along with The Sun Also Rises and On The Road. Yet it seems to have more in common with its antecedents than with anything that has come since. There has been no equivalent novel, or phenomenon, in the post-Internet world. This is likely because the great, generation-defining, post-Internet novel is being written, in a thousand tiny disconnected shards, on the Internet, every day.

But if Generation X is ensconced as a relic, it deserves to be celebrated as a book. To read it today is to realize how artfully it both created and captured its moment and how prodigiously well-suited Coupland was to the task. He possesses a voracious eye for observation and a ludicrous skill for aphorism. (The famous marginalia, full of coinages and portmanteaus, seem almost like a boast.) He chronicled a generation that didn’t yet know it was a generation—those marketing-saturated, message-averse post-Boomers who were afflicted by a moral malaise and the millstone of their apparent overeducation. “I work from eight till five in front of a sperm-dissolving VDT performing abstract tasks that indirectly enslave the Third World,” is how one character, Dag, describes his life. For the record, no one in the ’90s actually talked that way. But everyone wished they talked that way.

Reading the book again, I’m reminded not of the phenomenon but of the feeling I had that this book had been written especially for me—which is, of course, the reliable mark of a lasting novel. And when I look at my own aging edition—you know exactly what it looks like; every edition of this book looks the same, with its band of clouds and its subtitle, “Tales For An Accelerated Culture,” in block letters, like the lingering handstamp from last night’s concert—I wonder if the handprint inside the front cover might actually be mine. Maybe Coupland traced my hand that night in the bookstore in Montreal, not his. Now that I think of it, that seems right. So I put my hand inside it. It fits.

Margaret Atwood on

Kiss of the Fur Queen

by Tomson Highway

Published in 1998, Kiss of the Fur Queen topped the bestseller list for many weeks. It was a pioneering work, as it dealt with two subjects that up to that time were not widely spoken about: the abuses, both physical and sexual, that took place at the residential schools set up for First Nations children, and gay lifestyles and identities among First Nations people. It was among the first books to tackle such long-repressed and inflammatory subjects, particularly the residential schools abuses. That story has been unfolding in the eyes of the public for more than a decade now, but it may fairly be said that Tomson Highway wrote the first chapter.

Highway was no stranger to pioneering and innovation. He was early on the scene as a playwright—The Rez Sisters made a big splash in 1986, many other plays followed, and Highway was the artistic director of Native Earth Performing Arts from 1986 to 1992. These were risky ventures, and they cut a pathway that many others have followed.

But why did this kind of activity seem so new, so unprecedented, in the 1980s? In the 1960s, there were hardly any works by First Nations poets, playwrights or fiction writers. The painter Norval Morrisseau had become known in the 1970s, but in literature, the age of John Richardson’s Wacousta and Pauline Johnson’s narrative poetry was long gone. No one had arrived to fill that gap in written work by First Nations artists, and the residential schools system—dedicated to expunging anything “Native” from the minds of the young—is certainly partly responsible. How can you write what you know if what you know is an erasure?

It was Highway’s genius to tell the story of that erasure: what it was like to live through, what effects it had on those who suffered it, and how—despite that created and painful blank—older traditions, beliefs and long-familiar figures could still make their way back to the surface of consciousness. “The return of the repressed” is a psychological term, but now—in the early 21st century—it might as well also be a sociological-anthropological one, as many diverse groups and communities work busily at digging up what previous generations worked so hard to bury. Those who do the first unearthings are not always thanked. More often they may be criticized—they have spoken the unspeakable, they have mentioned the unmentionable, they have violated a code of silence. Also they have brought shame, for in these situations it may be blame that attaches to the perpetrators, but it is shame that attaches to the victims. So it is with rape, and these children were raped.

Kiss of the Fur Queen—with its glancing reference to that other well-known gay work, 1985’s Kiss of the Spider Woman—is the semi-autobiographical account of two Cree brothers, taken from their family and sent off to the abusive priests. It was the law that children had to go to schools, and when communities did not have schools, residential schools were the only choice open to them. The brothers’ names were changed, and the process of forced erasure was begun. Luckily they had a guardian: the trickster deity, one of whose names is Weesageechak (from which the grey jay gets its northern nickname, “whiskeyjack”). This deity is genderless and can take any form it pleases. In Highway’s novel, for instance, it speaks as a fox, whereas in his two “rez” plays, the name is Nanabush; male in one play, female in another.

One of Highway’s points is that the theft or obliteration of a language is also the theft or obliteration of a whole way of viewing reality, for Cree has a gender-neutral article that can be used of sentient beings, and English does not.

It has taken more than 20 years for Highway’s work to truly come into its time. It was well ahead of that time, but right now it is more relevant than ever.

Reprinted with permission from the “25 Most Influential Books” anniversary supplement, featured with the November issue of the Literary Review of Canada.