How artist Stan Douglas recreates scenes of political unrest

With his latest exhibit, “2011 ≠ 1848,” Douglas represented Canada at the Venice Biennale

(Portrait by Evaan Kheraj)

Share

Earlier this year, the Vancouver-born visual artist Stan Douglas represented Canada at the Venice Biennale, one of the most prestigious art exhibitions in the world. It was the type of career-crowning opportunity that could fluster even the most seasoned pros.

Douglas, who’d shown at the biennale several times before, kept his cool. He attended a party DJed by Detroit musician Carl Craig, went to a few galleries to look at the work of Italian painter Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, and hung out with some of the other famous artists in attendance. “It gets easier and easier every time,” says Douglas, who lives in Vancouver and Los Angeles and is the chair of ArtCenter College of Design. Since the early ’80s, Douglas has been shown pretty much everywhere—MoMA in New York City, the Tate in London, the Centre Pompidou in Paris. So, in a sense, headlining the Venice Biennale was a long time coming.

Douglas is an astute social critic, often using film and photography to reimagine and rediscover the past, whether it’s by recreating Penn Station in the early 19th century or Vancouver’s Gastown Riots in 1971. He also has a knack for focusing his lens on moments of political unrest. In his 2012 series Disco Angola, for example, Douglas documents two worlds in the 1970s: New York’s disco scene and the civil war in Angola.

His latest work—2011 ≠ 1848, which made its debut in Venice—offers a similar juxtaposition. The exhibit is made up of two parts: a series of photographs showing political protests from 2011 (Occupy Wall Street, the Arab Spring, the London riots) and a two-screen video installation depicting a hip-hop cypher, which involves freestyle rapping. At first glance, each protest image looks like a photograph taken in real time, as if Douglas documented the incidents as they happened. But he didn’t: these pictures are fabrications, made by digitally rendering models and props onto a photo template. To recreate each scene, Douglas researched the events, examining photos, articles and videos—anything to help him reimagine the moment. The result is that Douglas becomes an omniscient storyteller, able to re-examine history by packing complex political turmoil into a single, striking image.

The video installation is deceptive, too. It features two screens on opposite sides of the room, facing each other. On one, the U.K. grime artists TrueMendous and Lady Sanity; on the other, the Egyptian mahraganat artists Joker and Raptor, who play electronic folk music. As the videos play on separate screens, it seems like the artists are rapping back and forth in a call-and-response, listening intently before delivering their rebuttal. Think again. Each video was filmed separately and stitched together afterwards, merely creating the appearance of a live dialogue.

So what does it all mean? Well, there are some clues in the title of the exhibit. Starting in 1848, there was a series of political upheavals in Europe, known as the Springtime of the People, that brought sweeping changes to governance but largely ended in failure. As the ≠ symbol (which means “does not equal”) indicates in the exhibit’s title, Douglas thinks these years were similar but not quite the same. In 2011, events like the Arab Spring were politically promising but didn’t bring many tangible changes. “The events of 2011 were policed and ignored,” says Douglas.

With the video installation, Douglas uses music to draw a connection between the uprisings. During the London riots, grime became an unofficial soundtrack of the movement; throughout the Arab Spring, mahraganat music played a similar role. Douglas wants to offer a utopian idea of how those two cultures could have communicated using music, which overcomes language and geographic barriers. He shows the artists in conversation, connecting, without them ever interacting at all.

Since the biennale, 2011 ≠ 1848 has been sweeping across Canada, with stops at the Polygon in Vancouver, the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa and, most recently, the Remai Modern in Saskatoon, where it’s on display from January to April. Here, Douglas describes how he created some of his most indelible images.

1: Vancouver, 15 June 2011

STAN DOUGLAS: “The people who rioted following the Canucks’ loss in the Stanley Cup enjoyed upturning the power dynamic. Vancouver is a place that’s inequitable. People can’t afford to buy or rent, which leads to a general sense of discontent. For the plate shot showing the background, we had to recreate the old Canada Post building using CGI, because it’s now being renovated by Amazon. In the middle, that’s the same model of truck that was burned at the protest. We found the truck and hired a pyrotechnical team, who lit it on fire at the PNE Amphitheatre in Vancouver. We used some of the same performers who appeared in another shot we did depicting Occupy Wall Street, except they’re shot from the front here. All the costumes are historically accurate based on what people were wearing in reference photographs.”

2: Tunis, 23 January 2011

“This event took place near the beginning of the Arab Spring. I first saw images of it in European news footage. People were out in the streets, talking politics, disobeying curfew. Early on, there was a lot of optimism. The police weren’t arresting anyone. But the revolution didn’t pan out the way everyone wanted. We planned to shoot the plate shot from a hotel across the street, where most of the news coverage was filmed during the event. But the hotel has since been condemned, so we stationed our photographer at an office building next door. When I’m directing shoots remotely, I give the photographer direction over emails and phone calls—lots of back and forth. The people in this image are also performers.”

3: London, 9 August 2011 (Pembury Estate)

“This image depicts the London riots, following the shooting of a 29-year-old Black man named Mark Duggan. I went back to the location six years after the event. During my research, it took me a while to figure out where everything happened. I got GPS coordinates by referencing hours of Sky News footage of the event and Google Maps, and then I flew overhead in a helicopter and shot my plate shot. I chose this vantage point because it showed the entire housing estate. Once I had the backdrop, I had to add the protesters, police, onlookers, fire and smoke, which we clipped from video footage of the actual event. I enhanced the flames and smoke with CGI.”

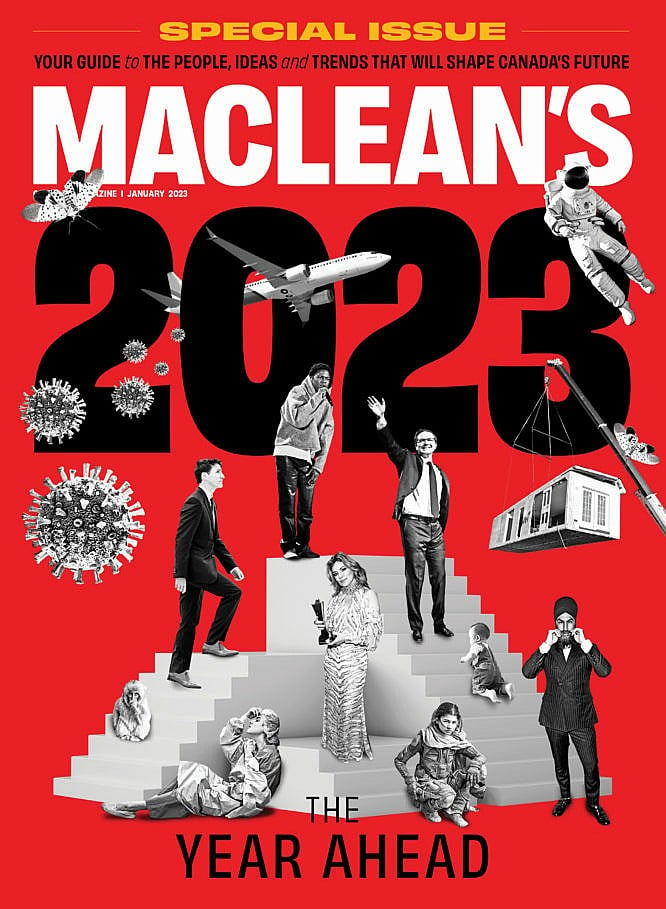

This article appears in print in the January 2023 issue of Maclean’s magazine. Buy the issue for $9.99 or better yet, subscribe to the monthly print magazine for just $39.99.