With widescreen TV, more can be less

Old shows are being reformatted to fit modern TVs. It looks weird.

Share

Remember when widescreen movies were cropped to fit television screens, and filmmakers like Spielberg and Scorsese campaigned to get them shown as the creators intended? Well, today TVs are widescreen, and that means big changes for any show that isn’t in that format—meaning almost any show made before this century. Toward the end of 2014, purists were stunned to learn that The Wire, one of the last major dramas in the nearly square 4:3 aspect ratio of older TVs, is being reformatted for high-definition widescreen. If perhaps the most revered TV drama of all time isn’t free from tampering, nothing is. “We’re back to the opening disclaimer found in videocassettes and broadcast TV: ‘The following has been formatted to fit your screen,’ ” says John Pavlich, of the podcast Sofa Dogs.

Older shows have been quietly altered for some time now; high-definition broadcasts of Seinfeld or Friends are in widescreen, even though the shows weren’t. But recently there have been more high-profile, controversial examples. At the same time as the changes in The Wire were announced, 20th Century Fox unveiled a widescreen remaster of the early seasons of Buffy the Vampire Slayer, which Todd Vanderwerff of Vox referred to as “ruining” the cult series.

In 2014, when the FX network showed a marathon of every episode of The Simpsons, the episodes were in the modern 16:9 widescreen ratio, with the top and bottom of the picture cut off to fit that shape. Even old shows can’t escape the hunger for a more rectangular look: Hogan’s Heroes has been seen on cable in fake widescreen.

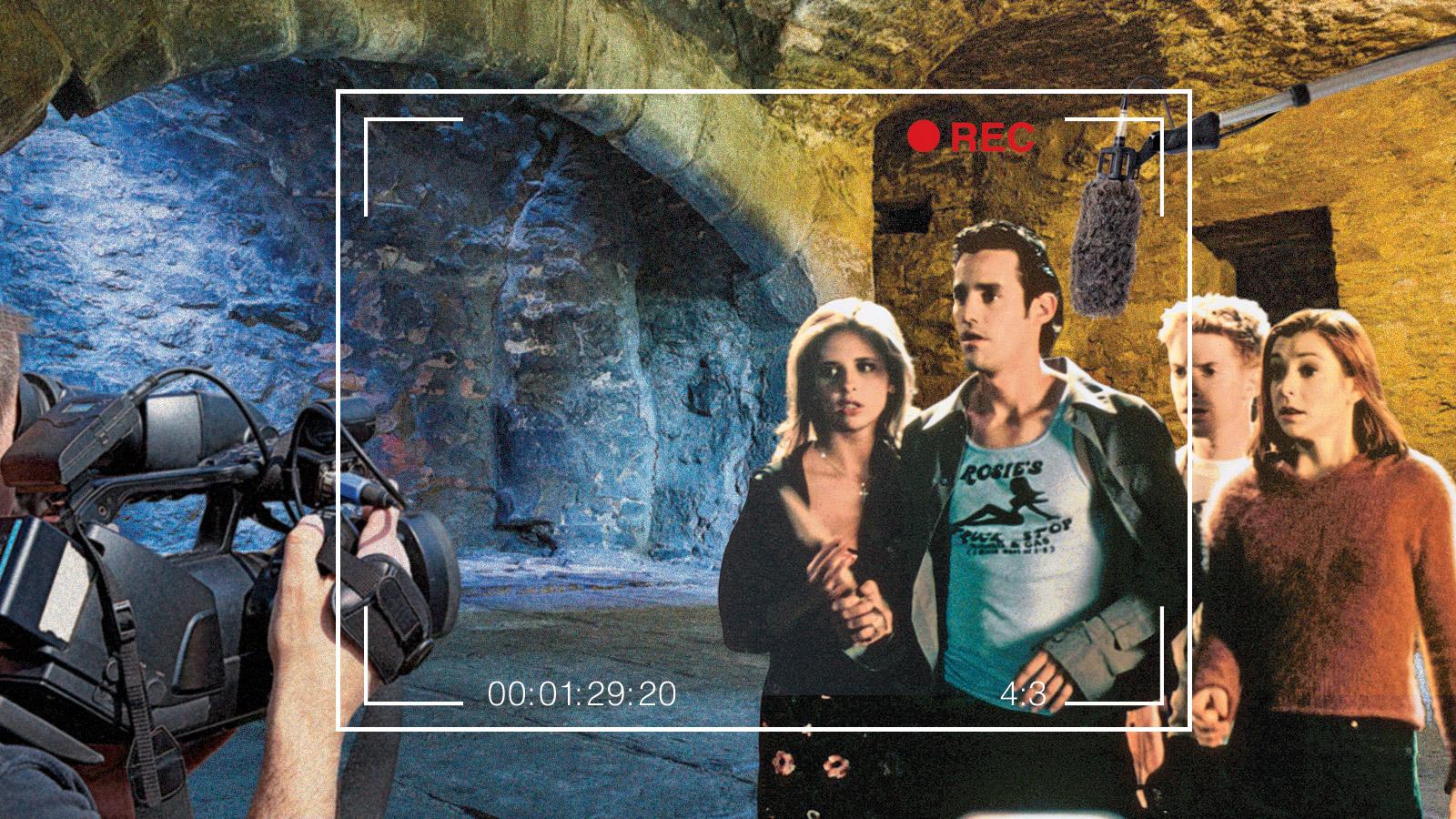

Remastering an older show in this format means changing the way every shot is framed, either by cropping the picture, or finding extra visual information on the sides. Cropping often results in mutilation: “The tops of heads are getting cut off,” explains Pavlich, who wrote an article calling attention to mistakes in Buffy episodes. “Pertinent hand-held items are now offscreen. It looks like a drunk was operating the camera.” The alternative, showing us more on the sides, can reveal things that were never meant to be seen: the widescreen Buffy expands the frame to display crew members, microphones and the ends of sets. It makes the show more surreal than it was supposed to be.

Creators, who are often not consulted on these changes, have had divergent reactions to them. “Widescreen Buffy is nonsense,” wrote creator Joss Whedon. But The Wire creator David Simon wrote on his website that today’s audiences may not accept the smaller screen, and “if a new format brings a few more thirsty critters to the water’s edge, then so be it.” Simon’s attitude disappointed some fans, like Stephen Bowie of the Classic TV History Blog: “I would argue the opposite—either watch The Wire as it’s supposed to be seen, or just don’t watch it.”

But the latter is a real possibility. Today’s viewers complain when shows have black bars on the sides (the only way to preserve the old shape), and will go to great lengths to avoid it: Pavlich notes that when a show is broadcast in 4:3, many people will use their TVs to stretch the picture or zoom in on it. “Sure, what you’re watching now looks atrocious but hey, at least it’s in sacred ‘widescreen,’ and that’s what really matters.”

That means networks today are reluctant to take a show that isn’t in the widescreen format their customers now prefer. A narrow picture may be like black-and-white photography, something that seems inherently old-fashioned. Chris Wade wrote in Slate that he enjoyed the cropped version of The Simpsons because it had been “optimized for 2014.”

Just because shows are changed now doesn’t mean they always will be. It took years of lobbying to get widescreen movies shown properly on the old TVs, and similar campaigns could help shows like Buffy. But until then, shows may face the choice between going widescreen and being obsolete, and it won’t just stop with recent classics. “If Netflix were to start saying, ‘We’ll only license Gomer Pyle or Hill Street Blues if you give us widescreen masters,’ ” Bowie says, “that’s when it really gets scary.”