One diamond’s dark and mysterious past

From 2013: Meet the Maltese Falcon-like gemstone that sparked a five-year storm of desire, political intrigue and crime

Share

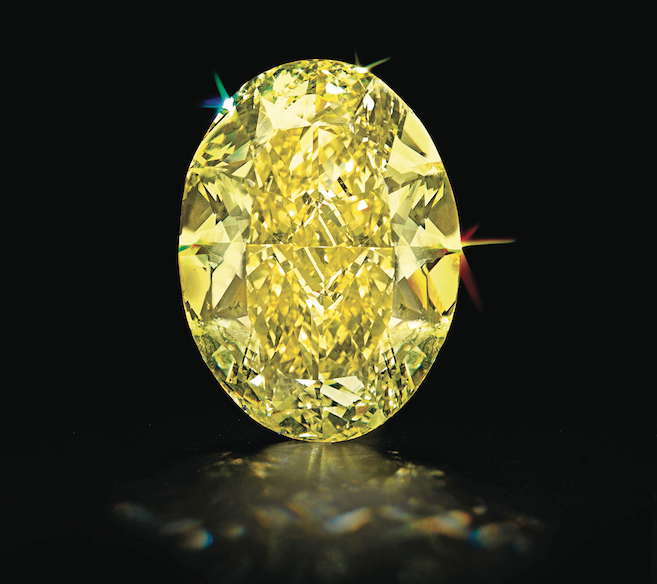

The diamond weighs in at 68 carats and, when held to the light, reveals only cloudless perfection, an oval stone with a flawless heart. It glows candy yellow—“fancy intense yellow,” in diamond-trade parlance—but its simple elegance belies a dark past. Last October [2012], when Christie’s New York put the diamond up for auction at its American headquarters in Rockefeller Plaza, five bidders “duked it out until a tenacious U.S.–based dealer finally won,” reported Rapaport Magazine, the diamond industry organ, noting its final sale price of $3,162,500—“$46,000 per carat.”

The diamond’s anonymous buyer very likely does not know of the stone’s criminal history—that U.S. federal court filings refer to it as the “Defendant Diamond”—nor of its association with the shadowy Canadian businessman who first transported it to Manhattan, where he sold it to a Fifth Avenue jeweller for $1 million.

Since its discovery in the arid diamond fields outside Hopetown, South Africa, in November 2008, the stone has criss-crossed the Atlantic Ocean three times—twice in the custody of U.S. immigration and customs enforcement agents—and become the subject of a civil forfeiture action brought against it by federal prosecutors in New York. That suit, United States of America v. One Polished Diamond Weighing Approximately Sixty-Eight Carats, filed in federal District Court for the Eastern District of New York in May 2010, effectively put the diamond under arrest and brought it into the court’s custody. The suit, just one of a fascinating class of so-called in rem actions that treat pieces of property as human beings, adds even more complexity to the story of the diamond, a precious Maltese Falcon object that was for five years caught in a maelstrom of desire, South African political intrigue and international crime.

But if its sale at Christie’s in October released the diamond from that swirling and improbable narrative, Chatham, Ont.-born Dennis van Kerrebroeck remains ensnared by it: he’s being held at Johannesburg Medium A Correctional Centre, a notoriously overcrowded prison where TB, gang violence and sexual assaults are rampant. His is not an ordinary criminal case. Late last year, a wealthy, politically connected South African businessman described van Kerrebroeck, 33, as an “enemy of the state” for his alleged role in stealing the diamond. Van Kerrebroeck otherwise stands accused of crimes too similar to the plot of a classic Hollywood heist film not to strain credulity: the theft, by way of an intricate cat-and-mouse game with a South African gem dealer and customs officials at New York’s John F. Kennedy International Airport, of the diamond. In the fall of 2009, the time of the alleged caper, that jewel still remained unpolished and uncut—a bruising, 143-carat rock.

A one-time pro-rugby hopeful with dual Canadian-Belgian citizenship who grew up in staid Waterloo, Ont., van Kerrebroeck was charged with spiriting the stone out from under the noses of customs officials and his associate at JFK, to Taly Diamonds, the Fifth Avenue jeweller to whom he sold it. In short order, Taly set about grinding, polishing and refining the 143-carat stone. “This process,” as court documents later put it, “transformed the rough diamond into the 68-carat polished Defendant Diamond.” U.S. immigration and customs enforcement agents later seized the oval-cut gemstone and, in a legal gambit at once strange and romantic, filed suit against it.

That complaint may sound far-fetched, but it is only one of a large group of in rem actions, frequently undertaken in the U.S. Meaning “against a thing” in Latin, in rem denotes a legal proceeding rooted in ancient maritime and real estate law, where these actions were in general directed at aristocratic estates, ships or flotsam discovered bobbing aimlessly in the sea. The proceedings rely on the legal fiction that a piece of property is guilty of an offence, and is therefore subject to seizure and, ultimately, forfeiture.

The classic in rem case, like that brought against the 68-carat diamond, allows the court to take physical control over a disputed piece of property while it determines ownership. “If there was a dispute about a ship, you would seize the ship and treat it as if it were a human being,” says Arthur Miller, a specialist in civil procedure who teaches at New York University School of Law. But the legal fiction at the heart of in rem proceedings eventually led to a deluge of odd-sounding case names stretching back to the early 20th century, when these actions began to flourish in American courts. “Like so many things in the law, it was the genie that got out of the bottle,” Miller says. “It moved from real estate to ships to machines, all the way over to intangibles, like stocks, bonds, bank accounts and all the rest.”

United States v. Forty Barrels and Twenty Kegs of Coca-Cola, for example, is a 1916 suit laid on the grounds that a shipment of Coca-Cola originating in Atlanta, and headed for Chattanooga, Tenn., was mislabelled because the product “contained no coca and little, if any, cola.” Another celebrated case, United States v. One Book Called Ulysses, led to the landmark 1933 decision that the long-banned 1922 novel by James Joyce was “a sincere and serious attempt to devise a new literary method for the observation and description of mankind,” and was therefore not obscene. Bizarre in rem cases continue to capture within their titles the gamut of human experience, from the federal court’s 1992 complaint against a “Fully Mounted Sheep”—this concerned the horns and hide of a “respondent sheep” hunted, killed and skinned in Pakistan, then illegally transported to Arlington, Texas—to United States of America v. One Oil Painting Entitled Femme en blanc by Pablo Picasso, which dealt with a Nazi-looted canvas, to, last year, United States of America v. One Tyrannosaurus Bataar Skeleton, involving the allegedly illegal importation of Mongolian dinosaur bones.

The diamond complaint had already been filed by the time South African police arrested van Kerrebroeck on Feb. 27, 2011, in Sandton, an affluent Johannesburg suburb, on fraud- and theft-related charges stemming from the alleged diamond heist in New York. Van Kerrebroeck maintains his arrest was illegal and that South Africa does not have jurisdiction over the diamond matter; his theft charge has since been dropped. Denied bail because he is not a South African national, he has been in jail ever since, awaiting a fraud trial now slated for June; he and his attorney, Nardus Grove, say that Barry Roux—internationally known after securing bail for Oscar Pistorius, the paralympic runner accused in the murder of his girlfriend, Reeva Steenkamp—will defend him.

Interest in van Kerrebroeck’s case in South Africa is strangely far-reaching. In December, Sandile Zungu, a wealthy South African businessman described by London-based Africa Confidential, a respected journal, as “a key figure” in South African President Jacob Zuma’s circle, called van Kerrebroeck an “enemy of the state” in Beeld, the country’s largest Afrikaans-language daily newspaper. “Our diamond is gone,” Zungu, who once had a business interest in the mining company that discovered the diamond, told investigative reporter Jacques Pauw. “To this day, we still have not seen a cent for it.”

For his part, van Kerrebroeck says he is the victim of a vast and elaborate scheme, perpetrated by his mining-sector associates in collusion with police and South Africa’s court system, to extort money from him and keep him in jail. A fast-talking dealmaker who in photographs exhibits the thick-necked bearing of a former rugby player, van Kerrebroeck claims he was duped into buying the diamond by his South African contacts, who he says illegally transported the stone out of South Africa, and who sought to abscond with money van Kerrebroeck placed in escrow as proof of funds in the deal. “Clearly, this diamond was illegally exported,” he told Maclean’s from prison. “How can I defraud someone when they’re actually defrauding me? They don’t go to court to adjudicate things; they pay a police officer like they’re ordering something at McDonald’s and say,‘Go and arrest that guy.’ ”

Van Kerrebroeck says he arrived in South Africa in 1998 to play as a flanker with the Durban Crusaders rugby club—an elite sport in a country where rugby is a hugely important and competitive game. Later, he says, he was attending the University of Western Ontario when one of his old South African rugby mates suggested they go into the diamond trade. Van Kerrebroeck says he ended up opening an office for his friend’s company in the European diamond hub of Antwerp, no doubt helped by his Belgian citizenship. It was his entry to the business that would lead him to travel throughout Africa—and would ultimately land him in jail.

The diamond first came to his attention around Christmas 2008, when a broker approached him about the gemstone, then still located in South Africa. That deal went nowhere. But on June 30, 2009, the broker wrote again to explain that the diamond was still for sale and now in Geneva, freeing it of export hassles in the country of its birth. “Ready to sell yet??????” van Kerrebroeck replied a month later in an email that would become part of the public record in New York. “I thought, ‘Okay, if they haven’t sold it in eight months, it’s bargaining time,’ ” he told Maclean’s. “Let’s go to Geneva.”

In Switzerland, van Kerrebroeck met with Adrianus Vriend, who he believed was acting as a representative of Higgs Diamonds Pty. Ltd., the firm that unearthed the diamond in conjunction with Jasper Mining Pty. Ltd. According to court documents, van Kerrebroeck, operating through his own Nevada-registered company, Belgo-Nevada, agreed to pay Higgs $3.3 million for the uncut stone, sealing the deal with a letter from an escrow agent guaranteeing payment based on a deposit of $4 million. Van Kerrebroeck and Vriend then boarded a Swissair flight bound for JFK “together with the Defendant Diamond,” the complaint reads.

Those court documents go on to allege that, upon landing in New York, van Kerrebroeck handed the diamond over to border agents, then turned around and told Vriend a discrepancy in the paperwork was holding up the stone’s passage through customs. That same night, a Higgs executive learned that the escrow account had been closed and the balance withdrawn, court documents say. All too soon, federal prosecutors allege, van Kerrebroeck, working alone, had retrieved the diamond from customs and sold it. Investigators with the office of the attorney general of the state of Nevada later found that the escrow officer who signed the letter he used to solidify the diamond deal—Jennifer Hunt—was “a fictitious person.”

Van Kerrebroeck disputes much of this account, and weaves a story as dark and convoluted as the grittiest 1940s film noir: Vriend, he says, actually accompanied him to the Fifth Avenue jeweller to sell the diamond, and the pair went on to travel together to Toronto. Van Kerrebroeck says the escrow account he opened in Nevada was only meant to show proof of funds, and that he would have paid for the diamond by other means, had his associates not vanished before he could do so. Indeed, he says, their real object all along had been to swindle him. “The long and the short of it is, don’t do business in South Africa, because they’re crooks,” he says. “You can’t trust any single one of them.” (To complicate matters further still, Higgs denies in court filings that it had any knowledge of Vriend’s dealings with van Kerrebroeck, or that David Griffiths, identified as a Higgs shareholder and executive in the federal suit, and who van Kerrebroeck says was in on the deal, was acting on its behalf.)

The summer after the federal court seized the stone and filed the diamond complaint, both Higgs and Taly, the Fifth Avenue jeweller, entered claims to it. Then, with what federal prosecutors saw as remarkable chutzpah, so did van Kerrebroeck—the very person they alleged stole the diamond in the first place, and who admits in his own submissions to selling it. The withdrawal of his claim later allowed Taly and Higgs to work out a deal by which the diamond would be sold at auction, with the proceeds split between the two firms.

There remained just one hurdle: the stone had to be entered as evidence in the criminal proceedings against van Kerrebroeck, who by this time had been arrested in South Africa amid a swirl of new allegations. With the diamond in their possession, U.S. immigration and customs enforcement agents flew to Johannesburg and escorted the diamond to court. The return of those agents to the U.S. with the diamond, and its delivery to Christie’s, closed the case of United States of America v. One Polished Diamond Weighing Approximately Sixty-Eight Carats. Diamonds, as it turns out, are not just the stuff dreams are made of, but of court cases and, for van Kerrebroeck, of nightmares, too.

Update: Van Kerrebroeck was held for 28 months before signing a plea deal for his freedom. He was released in 2013 and returned to Waterloo.

Read the court document behind the intriguing case of the 68-carat diamond: