The secrets to Robert Altman’s success

Ron Mann’s new doc aims to answer film’s ultimate question: What is ‘Altman-esque’?

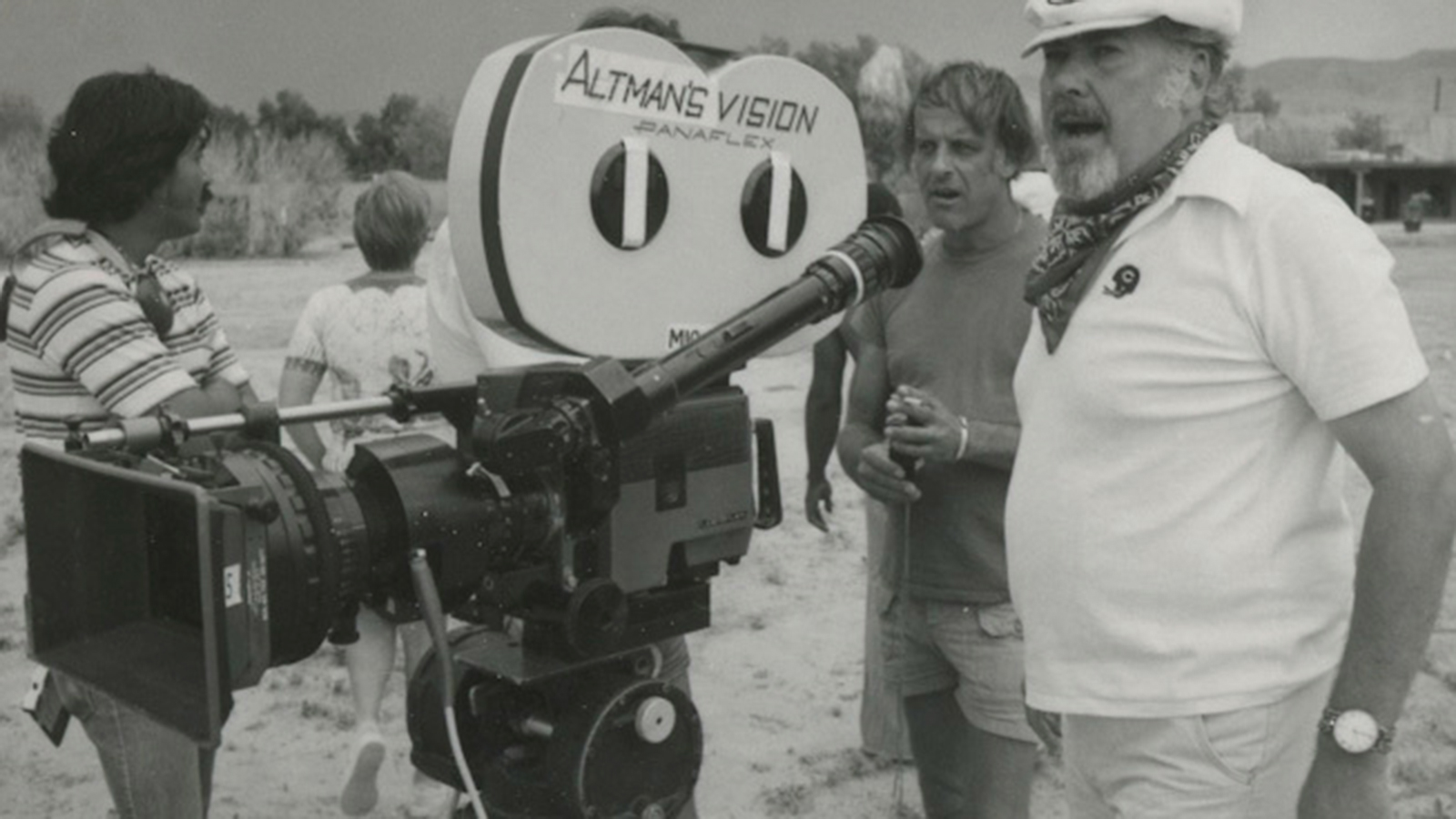

(TIFF Film Reference Library)

Share

Robert Altman never won an Academy Award for best director. Let that fact sink in for a moment while you quickly compile a list of every other filmmaker who has been blessed with a golden statuette while the director of M*A*S*H, Nashville and The Player went ignored. Yes, Altman did eventually receive an honorary award in 2006—just a few months before he died at 81—but the fact is that one of cinema’s greatest artists went unrecognized by the arbiters of Hollywood for his entire career, and all the Academy could offer was a belated “oops.” Fortunately, Altman’s career survived Oscar’s trespasses, and his legacy can be felt in today’s greatest cinematic voices, from the quiet independent work of David Gordon Green to the epic, multi-level tales of Paul Thomas Anderson.

Now, in a bid to shed light on just how much Altman helped to define the medium, Canadian documentarian Ron Mann delivers his new film, Altman. The documentary—which was just selected for the Venice International Film Festival and will kick off an Altman retrospective at Toronto’s TIFF Bell Lightbox on Aug. 1—uses rare interviews and a wealth of archival clips to paint a portrait of Hollywood’s quietest innovator, who traversed genres (from the subversive western drama of McCabe & Mrs. Miller to the brutal heartache of Short Cuts) as easily as he did technology (he was one of the first directors to utilize high-definiton video with his 2003 dance drama, The Company, and pioneered the use of overlapping dialogue).

The new doc is partly a labour of love for Mann, who considers himself one of the director’s biggest admirers, and partly a rebuke to the standard “let’s-all-honour-an-artist” tack that so many artist documentaries take. While there are plenty of old war stories on offer in Mann’s film, he doesn’t let his interviews with Altman collaborators and admirers ramble. Instead, Mann pulls a fast one on his subjects, asking them only a single question: “What does the word ‘Altman-esque’ mean to you?” The enlightening and elegant answers from the likes of Elliott Gould, Keith Carradine and Lily Tomlin add a personal touch to the documentary that’s, well, more than a little Altman-esque itself.

“Bob was a big fan of Kurosawa’s Rashomon, particularly the idea that there are so many different interpretations of one event or idea, which made me think of having different people try to define who Bob was,” says the Toronto-based Mann. “Everyone has a different defintion of what’s ‘Altman-esque,’ and everyone is right.” The trick also neatly echoes Altman’s own work, which was so often populated by characters who had to face countless and overwhelming versions of the truth, be it the paranoid movie executive played by Tim Robbins in The Player, or the upstairs/downstairs mind games of those stuck in Gosford Park.

But before Mann had even attempted to explore the many sides of Altman, he first had to get permission from the director’s greatest collaborator: Kathryn Altman, his wife of 47 years. “Because of the enormous strains of making films, it takes a very special person to be married to a filmmaker, especially someone as prolific as Bob,” Mann says. “Kathryn was committed to his art as much as him.” After setting up a meeting with her at the 2011 Torino Film Festival, which was running a retrospective of Altman’s work, Mann was able to convince Kathryn that he would treat her late husband’s career with the respect it deserved. “When Ron first came to me, he seemed a little quirky, you know? So I thought that was good. I thought that was really Altman: not being middle of the road,” says Kathryn, who married Robert in 1959, both having waded through two failed marriages beforehand. “Like Bob, Ron also has such a good eye for the screen, for editing a life together. I think it would have really pleased Bob.” (Adds Mann: “I made Kathryn one promise: ‘I will not f–k it up.’ “)

Although a large portion of the film is focused on Altman’s work, his relationship with Kathryn forms the heart of the picture, which made it all the more difficult for his widow to watch, seven years after his passing. “It’s tough, it’s very emotional. After watching the original cut, I had to step back and think, because there was a lot of footage of our life that I had never seen before,” says Kathryn. “Ron has made it so real, and also so heartrending. It’s a good combination, though.”

While Mann touches on all the expected milestones of Altman’s career—the unexpected triumph of M*A*S*H, the director’s self-imposed exile to Paris after the failure of Popeye—perhaps the most surprising element is the extent to which the filmmaker toiled in the depths of the television industry in his early years. After Altman’s debut 1957 feature The Delinquents caught the eye of Alfred Hitchcock, the Psycho auteur hired the young filmmaker to direct his CBS anthology series. That auspicious start sparked a lengthy career on the small screen that only ended when Altman abruptly quit Kraft Suspense Theatre when the advertiser refused to cast a black actor in an episode. Fortunately, this part of Altman’s CV hasn’t been lost to the attics of IMDb, and is illustrated in the documentary with a wealth of archived clips, which Mann unearthed during a research stint at the University of Michigan library’s Mavericks of American Film collection.

“I thought I was going to be in Michigan for one week with one assistant, but I ended up staying six weeks with six assistants, just scanning photographs and digitizing files,” says Mann. “It was almost as if Bob left an audiovisual record of his life, a trail for me to follow.” The long weeks paid off, with the old footage providing Mann with a unique glimpse into Altman’s evolving—and increasingly rebellious—style. “He was really one of the top TV directors in the ’50s and ’60s,” adds Mann. “He pushed for realism, he broke the rules, but he kept on finding himself pushed up against the constraints of the medium, and of advertisers’ demands.” It’s no surprise that his films, including the politically charged Nashville and Tanner ’88, would underline Altman’s desire to constantly needle the system.

As for Mann’s own defintion of Altman-esque? “It’s simply heroic filmmaking. Bob was someone who was indestructible,” says the director, whose own filmography is littered with tales of rebels (Tales of the Rat Fink) and outsiders (Comic Book Confidential). “Throughout his life, Bob not only reinvented his approach to filmmaking, [but] the language of film itself. He constantly changed the game, which is what real artists do.” Oscar recognition be damned.