The truth about Cleopatra

It turns out the iconic last queen of Egypt was noticeably less beautiful but a lot smarter than we thought

Share

When Shakespeare wrote about how “age cannot wither” the “infinite variety” of Cleopatra VII, the last queen of Egypt, he meant to invoke the fascination she exerted over all who met her, but he could as easily been describing her enduring afterlife. For 2,000 years the Western world has loved, or at least loved to hate, its Eastern beauty, whether as doomed lover or immoral seductress. Dante put her in the second circle of Hell with the other “carnal sinners,” while Chaucer thought her a virtuous woman steadfast in love. Pascal believed her beauty was one of the accidental details upon which the axis of history turns: “Had Cleopatra’s nose been shorter, the face of the world would have changed.’’

When Shakespeare wrote about how “age cannot wither” the “infinite variety” of Cleopatra VII, the last queen of Egypt, he meant to invoke the fascination she exerted over all who met her, but he could as easily been describing her enduring afterlife. For 2,000 years the Western world has loved, or at least loved to hate, its Eastern beauty, whether as doomed lover or immoral seductress. Dante put her in the second circle of Hell with the other “carnal sinners,” while Chaucer thought her a virtuous woman steadfast in love. Pascal believed her beauty was one of the accidental details upon which the axis of history turns: “Had Cleopatra’s nose been shorter, the face of the world would have changed.’’

The broad sweep of her story is well known, and many of its details almost universally so: her seduction of Julius Caesar (to whom she had herself smuggled wrapped in a rug and unrolled before his feet); her fateful choice between the two men vying for the assassinated Caesar’s mantle (allying with Marc Antony rather than the eventual victor, Octavian, later Augustus Caesar); the conspicuous consumption (once taking a pearl valued at 10 million sesterces—enough to maintain 10,000 Roman soldiers for a year—dissolving it in a cup of vinegar and drinking it down, merely to display her wealth); and, of course, suicide by asp bite.

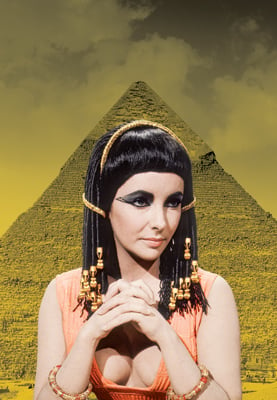

The intense theatricality of it all is why, despite considerable literary portrayal, Cleopatra’s presence in the Western imagination has always been primarily a matter of spectacle. There are dozens of paintings (with the pearl and the deathbed as favourite scenes) and ballets, plays and films, with Shakespeare’s endlessly revived Antony and Cleopatra—Kim Cattrall has just signed on for a fall run in England—and the 1963 film Cleopatra standing at the apex as twin icons. Best known for the scandalous public affair between stars Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton that seemed to mirror onscreen events, Joseph Mankiewicz’s cinematic hymn to wretched excess offers Cleopatra’s single most potent modern image.

But behind the pop culture scenes another force has been working on our understanding of Cleopatra. A half-century tide of scholarly revisionism impelled by a heightened awareness that history is written by the victors—meaning that our idea of Cleopatra is skewed by hostile Roman propaganda—and, above all, a feminist-inspired re-evaluation of one of the ancient world’s most powerful women, has constructed a queen who doesn’t bear much resemblance at all to Liz Taylor. Three recent studies—Cleopatra and Antony: Power, Love, and Politics in the Ancient World by Dianna Preston, Joyce Tyldesley’s Cleopatra: Last Queen of Egypt and Cleopatra: A Biography by Duane Roller—take a new look at the evidence and come up with a very different ruler.

Their Cleopatra is smarter, colder, tougher, decidedly unpromiscuous and noticeably less beautiful. An effective diplomat, administrator, naval commander and linguist, she skillfully managed her rich but weak realm in the face of growing Roman strength until her last years. A Cleopatra, in fact, who came very close to creating an Eastern empire that would have rivalled her Western enemy.

Born in 69 BCE, Cleopatra VII was heir to a 250-year-old Greek dynasty that began when Ptolemy I, one of Alexander the Great’s boyhood friends and generals, seized the most glittering prize in the conqueror’s disintegrating empire after Alexander died young. He moved Egypt’s capital to the new Greek-speaking city of Alexandria—two centuries later Cleopatra became the first of the family to speak Egyptian—reorganized the country’s economy and managed to die peacefully in his bed at 84, an age and a feat matched by few of his violent descendents.

After him the Ptolemies embraced native traditions of divine rulership and the incest that logically followed. (Who but a sister was worthy to marry Pharaoh?) So enthusiastically was the inbreeding embraced that the 16 roles of Cleopatra’s great-great-grandparents were filled by only six individuals, all of whom did double, and sometimes triple, duty as parents, spouses and siblings. The practice opened the door for the family’s equally divine females to occasionally rule (Cleopatra VII was not the first), made domestic life at court literally murderous (there were always equally eligible rivals around) and—perhaps—contributed to the family’s marked tendency to obesity. Such was Cleopatra’s family, and such too was Cleopatra: she had a sister and a brother killed, waged war against another brother, and seems to have run to the family plumpness. When Diana Preston asked an archeosteologist, a specialist in postmortem facial reconstruction, to create a model of Cleopatra based on her image on coins and the busts of other members of her inbred family, the result—fleshy-faced and hawk-nosed, with a protruding chin and an underhang beneath the jaw—was a woman far from today’s standard of beauty.

What then captivated Julius Caesar, the last man standing in the Roman Republic’s long disintegration, when he arrived in Alexandria? Cleopatra, 21 and losing her own civil war to her brother, Ptolemy XIII, saw her chance—Caesar, after all, was a notorious womanizer, whose troops used to bellow out lock-up-your-daughters marching songs about their “bald whoremonger.” She took a calculated risk, and literally threw herself at the 52-year-old Roman’s feet. Plutarch, writing more than a century after the fact, says “her beauty was in itself not altogether incomparable,” but her “conversation was inescapably gripping” because of her wit, intelligence and the “sweetness in the tones of her voice.” Caesar could have annexed Egypt or allied with Ptolemy. Instead, weighing his options—including the queen’s popularity with her people—he took Cleopatra’s side, and Cleopatra. Soon, Ptolemy XIII was dead, drowned in the Nile; a year later Caesarion, her son by Caesar, was born.

Mother and child were in Rome, scandalizing the likes of Cicero (the authentic voice of Roman misogyny and xenophobia) by their mere presence, when Caesar’s killers struck. Soon she was back home, skilfully deflecting the demands of the assassins for troops and money, and even leading her fleet out against them. After Antony and Octavian defeated the republicans, and Antony had assumed power in the east, he called her to Tarsus in what is now Turkey, the future birthplace of St. Paul.

Her arrival there in her royal barge with its golden stern was one of the great spectacles of the ancient world: purple sails billowed, pipes and lutes played, while Cleopatra reclined on a couch dressed as Aphrodite and clouds of incense from numerous burners floated ashore. Star-struck, Antony asked her to dine with him, but she requested he and his officers come aboard ship—subtly inviting Antony to Egypt. Thus began the series of lavish banquets, including the one with the pearl quaffing, that won over Antony—dazzled partly by Cleopatra and partly by the evidence of wealth he could use for eastern conquests. Antony, in turn, could and did give Cleopatra what she wanted: the execution of her last sister (in exile on a Roman-held island), expansion of the family kingdom, protection from other Roman client kings, and heirs of suitably noble blood.

For a doting mother who took her second lover only after her first was murdered, Cleopatra has had a lot of salacious press over the centuries. Yet her sexual morality approaches that of a vestal virgin in comparison with the men in her life: Roman aristocrats with life-and-death power over millions, a sense of entitlement dwarfing that of Tiger Woods, and a pre-Christian lack of guilt over sex.

When Octavian later put out propaganda on how Antony was shaming his Roman wife (Octavian’s sister, Octavia) by lolling about with an Oriental temptress, Antony replied in a letter written with what seems, to modern eyes, genuine puzzlement: “What does it matter to you where I stuff my erection?”

Both of Cleopatra’s love affairs had serious political—even personal—survival underpinnings, and in regards to the first one, it is difficult to tell, 2,000 years later, what love may have had to do with it, though she and Caesar remained close until his assassination four years later. But the intense relationship between Cleopatra and Antony—which produced three children, a Ptolemaic kingdom larger and more powerful than it had been in centuries, and lasted 11 years until renewed Roman civil war claimed their lives—was far more than a political alliance. Octavian propaganda cleverly played to Roman prejudice by claiming Cleopatra flattered Antony’s ego, matched him in decisiveness and decision-making, and was an equal companion in the fun, games and feasting he so enjoyed. “It was,” biographer Roller dryly comments, “also largely true.”

After the couple lost the naval battle of Actium to Octavian, Antony became depressed and suicidal, but Cleopatra kept looking to the future. Antony stabbed himself when he wrongly heard that Cleopatra had committed suicide. Roller thinks she put that rumour about to induce his suicide, thereby freeing her to bargain with Octavian. But most scholars disagree, citing ancient accounts of her behaviour at the time: after Antony died in her arms, she tore her clothes, clawed at her breast with her nails, and smeared her face with his blood, while calling him “master, husband, commander.” But even in her grief, she did not move to kill herself for more than a week, time spent desperately trying to save, if not her own life, Caesarion’s throne.

But when she realized Octavian planned to march her in triumph through the streets of Rome, Cleopatra was determined to avoid the humiliation. Somehow acquiring poison—the mystery of how she did so under close Roman guard eventually gave rise to the asp in a basket of figs story—she and two loyal attendants killed themselves. However much the ancient sources disparaged Cleopatra’s morals or political machinations, or the mere idea of an Eastern woman ruling Roman men, they are united in their respect for her courage and queenly nature. Plutarch records, admiringly, the response her dying maid Charmion gave when a Roman officer burst in and spat out, “A fine deed this!” Yes, Charmion agreed, “Nothing could be finer for this lady, the descendent of so many kings.”