Was moralizing—not immoral behaviour—Bill Cosby’s real undoing?

The judge who unsealed Cosby’s damning deposition is not the first to be enraged by the comedian’s hypocrisy

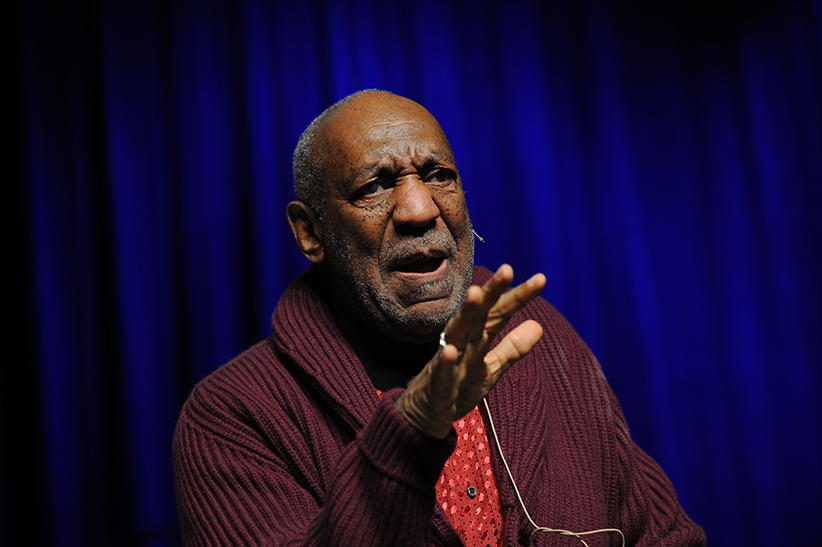

NEW YORK, NY – NOVEMBER 06: Bill Cosby performs at The New York Comedy Festival And The Bob Woodruff Foundation Present The 7th Annual Stand Up For Heroes Event at The Theater at Madison Square Garden on November 6, 2013 in New York City. Bryan Bedder/Getty Images

Share

What’s worse than being an alleged rapist? Being a hypocritical alleged rapist. When it comes to Bill Cosby, it may be that his moralizing, not his lack of morals, is what finally wrecked his career.

The final blow to Cosby’s reputation may have come this week when a U.S. district judge, Eduardo Robreno, chose to unseal documents that buttress the rape allegations against the comedian: On the judge’s authority, the Associated Press unveiled a 2005 deposition in which Cosby admitted obtaining Quaaludes (the sedative methaqualone) to give to young women he wanted to have sex with. Robreno’s rationale for making these documents public was that Cosby had set himself up as something more than a mere entertainer: “He has donned the mantle of public moralist and mounted the proverbial electronic or print soapbox to volunteer his views on, among other things, child-rearing, family life, education and crime,” Robreno wrote.

As Justin Moyer pointed out in the Washington Post, Robreno is referring in particular to speeches Cosby made in the ’00s, after most of the alleged incidents had taken place. He began to set himself up as an authority on family life and behaviour, admonishing African-Americans to be more responsible parents, and blaming youthful crime partly on bad parenting. His most famous statement was the so-called “pound cake speech” in 2004, in which he explained that good parenting taught him that it was wrong to steal: “I wanted a piece of pound cake just as bad as anybody else, and I looked at it and I had no money. And something called parenting said, ‘If you get caught with it, you’re going to embarrass your mother.’ ”

Speeches like these were discussed respectfully at the time, even by people who felt Cosby was engaging in too much victim-blaming. But it seems very likely that, if he hadn’t said these things, he would have gotten away with his private behaviour. After years of the media mostly ignoring the allegations against him (to the point that they were mostly left out of his first major biography), comedian Hannibal Buress finally drew attention to them again in a routine in which he attacked Cosby for his hypocritical moralizing and “smug, old, black-man” persona.

”Pull your pants up, black people,” Buress mocked Cosby as saying. ” ‘I was on TV in the ’80s. I can talk down to you because I had a successful sitcom.’ Yeah, but you raped women, Bill Cosby. So, brings you down a couple notches.” All the other reports and rumours about Cosby’s actions had done very little to make anyone care, even in show business, where the rumours must have circulated more widely; NBC was even planning to give Cosby a new sitcom. But Buress got people interested in the rape allegations by pointing out how little right Cosby had to pose as a moral icon. It was the hypocrisy, not the alleged rape, that caught the world’s attention.

Now, Robreno is saying much the same thing Buress did: It’s particularly important to know the things Cosby said and did in private, because they’re so at odds with his public statements. Robreno wrote that, while he wouldn’t have unsealed the documents if Cosby were just a star, the public has an interest in seeing “the stark contrast between Bill Cosby, the public moralist, and Bill Cosby, the subject of serious allegations concerning improper (and perhaps criminal) conduct.” But that means that if Cosby had never tried to portray himself as morally superior, he’d be fine.

The potential danger of this idea is that it elevates hypocrisy to the status of the worst of all sins. Buress, Robreno and others aren’t literally saying that hypocrisy is worse than rape, of course. But they are saying that Cosby needs to be exposed, because his private behaviour doesn’t match his public statements. Celebrities who behave badly but don’t moralize in public, on the other hand, are safe. Cosby is in trouble, at last, not because he behaved like Bill Cosby. It’s because he told other people not to be like Bill Cosby.