Annotations on Mark Carney’s speech about Dutch disease

Stephen Gordon: What the governor said and why he’s right

Mark Carney, governor of the Bank of Canada in Calgary, Alberta, on Sept. 7, 2012. (Todd Korol/Reuters)

Share

With any luck, today’s speech by Bank of Canada Governor Mark Carney will be the final word on the ‘Dutch Disease’ debate in Canada:

Some regard Canada’s wealth of natural resources as a blessing. Others see it as a curse.

The latter look at the global commodity boom and make the grim diagnosis for Canada of “Dutch Disease.”1 They dismiss the enormous benefits, including higher incomes and greater economic security, our bountiful natural resources can provide.

Their argument goes as follows: record-high commodity prices have led to an appreciation of Canada’s exchange rate, which, in turn, is crowding out trade-sensitive sectors, particularly manufacturing. The disease is the notion that an ephemeral boom in one sector causes permanent losses in others, in a dynamic that is net harmful for the Canadian economy.

While the tidiness of the argument is appealing and making commodities the scapegoat is tempting, the diagnosis is overly simplistic and, in the end, wrong.

This is an argument I’ve made several times — here, for example — but here I’m going to flesh out how Carney frames it.

Coinciding with this period of elevated commodity prices, the share of the manufacturing sector in Canadian GDP has declined since the turn of the century from 18 per cent to around 11 per cent.

For the promoters of Dutch Disease, this is the “a-ha” fact, with the coincidental relationship described as causal. With a broader view, however, it is evident that the decline in manufacturing is only partially in response to the rising exchange rate and, in fact, is part of a broad, secular trend across the advanced world (Chart 5). Major forces of globalisation and technological change have dispersed manufacturing activity across borders, increasingly concentrating the highest value-added stages of production in advanced economies.

In 1970, Canada’s manufacturing-to-GDP ratio was 6 percentage points below the average of members of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Today, it is 3 percentage points behind. Likewise, the share of jobs in manufacturing has declined, but not as steeply as it has in our commodity-importing neighbour to the south (Chart 6). Although the adjustment has been difficult, it has occurred over a longer period of time than the boom in commodity prices and, in general, Canada has not lost ground relative to other advanced economies.

In a nutshell, the long-term shift out of manufacturing is not a phenomenon unique to Canada.

The coincident strength of commodity prices and the Canadian dollar in recent years has been treated by some as prima facie evidence of Dutch Disease in Canada. But this diagnosis ignores the fact that the Canadian dollar is influenced by a diverse set of factors.

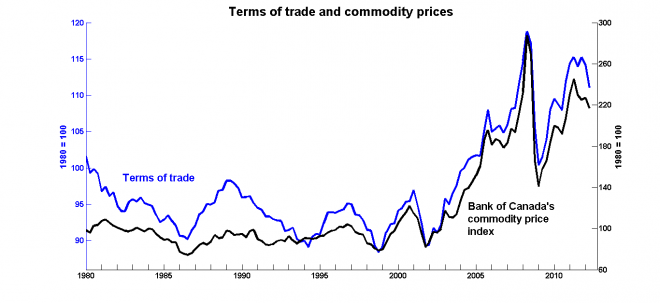

Commodity prices do play a role. Canada is a net exporter of commodities while our main trading partner, the United States, is a net importer. This causes our respective terms of trade to move in opposite directions in response to commodity-price changes. As a result, the Canada-U.S. exchange rate tends to appreciate when global commodity prices rise (Chart 7).

The expression terms of trade is something worth spending more time on. As the Wikipedia entry says:

In international economics and international trade, terms of trade or TOT is (Price of exportable goods)/(Price of importable goods). In layman’s terms it means what quantity of imports can be purchased through the sale of a fixed quantity of exports… An improvement in a nation’s terms of trade (the increase of the ratio) is good for that country in the sense that it can buy more imports for any given level of exports. The terms of trade is influenced by the exchange rate because a rise in the value of a country’s currency lowers the domestic prices for its imports but does not directly affect the commodities it produces (i.e. its exports).

This is a better way of thinking about the effects of higher commodity prices than in terms of the exchange rate. Glenn Stevens, who is now the Governor of the Reserve Bank of Australia – and who was once my classmate – put it this way:

When the terms of trade are high, the international purchasing power of our exports is high. To put it in very (over-) simplified terms, five years ago, a ship load of iron ore was worth about the same as about 2,200 flat screen television sets. Today it is worth about 22,000 flat-screen TV sets – partly due to TV prices falling but more due to the price of iron ore rising by a factor of six. This is of course a trivialised example – we do not want to use the proceeds of exports entirely to purchase TV sets. But the general point is that high terms of trade, all other things equal, will raise living standards, while low terms of trade will reduce them.

The link between commodity prices and Canada’s terms of trade is surprisingly tight (clicking on a graph opens a larger version in another window):

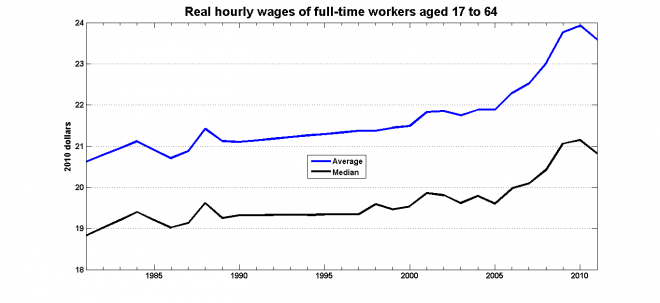

And so is the link to living standards. A recent Statistics Canada study notes that after 20 years of stagnation during the 1980s and 1990s, real wages finally showed some marked progress in the 2000s:

So it’s better to think about changes in commodity prices in terms of the terms of trade than on the exchange rate. After all, as Carney notes, there are other things that can and do affect the exchange rate:

But [the increase in commodity prices] is just the beginning of the story, accounting for about one-half of the appreciation of our currency over the past decade. Other factors also play important roles.

Since 2002, the U.S. dollar has depreciated against many currencies, including those of both commodity exporters and importers. The Canadian dollar has appreciated against the U.S. dollar by an amount similar to that of the currencies of two major commodity importers, Japan and the euro area (Chart 8).

Overall, the Bank estimates that about 40 per cent of the appreciation of the Canadian dollar since 2002 is due to the multilateral depreciation of the U.S. dollar.

The balance of the appreciation reflects forces other than U.S.-dollar weakness and commodity prices. In particular, a variety of attributes make Canada an attractive investment destination, including our sound public finances, resilient financial system, and credible monetary policy.

These strengths limit the downside risk associated with Canadian assets, making Canada a rare safe haven in a risky world.

This status is reflected in the behaviour of Canadian 10-year yields, which tend to decline at the same time as risky assets such as global equity prices. This correlation suggests that money flows into Canadian bonds in response to increases in perceived risk. Indeed, by this measure, Canada’s safe-haven status is second only to the United States and the United Kingdom (Chart 9). This was not always the case. During the Great Moderation, this correlation was essentially zero (Chart 10).

That said, Carney makes the point early on that, although the net effect of higher commodity prices is positive, that doesn’t mean there are no costs:

That is not to trivialise the difficult structural adjustments that higher commodity prices can bring. Nor is it to suggest a purely laissez-faire response. Policy can help to minimise adjustment costs and maximise the benefits that arise from commodity booms, but like any treatment, it is more likely to be successful if the original diagnosis is correct.

So what treatment does he suggest? A good summary of his recommendations is “eat your vegetables.” Firstly, Canadians should get past the notion that the path to prosperity lies in being the low-cost exporter of manufactured goods to the United States:

Research at the Bank and elsewhere suggests that, while oil and metals prices have historically moved with the business cycle in the advanced world, this relationship has broken down over the past decade. In particular, industrial activity in emerging Asia now appears to be the dominant driver of oil-price movements (Chart 15).6

Our reliance on the United States, which still takes nine times as many of Canada’s exports as fast-growing emerging-market economies, is an issue only if we expect U.S. underperformance relative to both history and the rest of the world to continue. Unfortunately, that is what we must expect for some time, as the United States goes through a difficult adjustment process.

In this context, the only way to recover the beneficial correlation between commodity prices and demand for Canadian manufacturing exports is to diversify our export markets toward fast-growing emerging markets. That is one of the many reasons why Canada is pursuing an aggressive, emerging-market-focused trade strategy.

For example, manufacturers in Ontario could take greater advantage of the opportunities just north of Montana:

Other new markets can be found at home. For example, as of November 2011, 255 Ontario firms were suppliers to the Canadian oil sands.7 As well, Ontario’s exports of mining-related services to Alberta grew 44 per cent in the last year measured. Capturing more of the value added in commodity production, from energy to agriculture, remains a tremendous opportunity for all of Canada.

We should also recognise that, in an era of high resource prices, better operating efficiency, improved resource management and products with a more sustainable environmental footprint make commercial and social sense. Advances in building energy efficiency, enhanced farm yields and power plant performance would pay immediate domestic dividends.

The list goes on: greater interprovincial mobility, enhanced skills, higher levels of investment. These would be good things to recommend under any circumstance, like eating your vegetables.

Carney concludes by saying:

Building on our strengths requires that we respond appropriately to the opportunities the global transformation affords us. That starts with recognising that the strength of Canada’s resource sector is a reflection of success, not a harbinger of failure.

The logic of Dutch Disease requires that we undo our successes in order to depreciate our currency. Taken to its natural conclusion, this logic dictates that we shut down the oil sands, abandon our resource wealth, have high and variable inflation, run large fiscal deficits and diminish our financial sector.

Such actions would surely weaken the Canadian dollar, but they would also weaken Canada.

In a world of elevated commodity prices, it is better to have them. Bank of Canada research shows that high commodity prices, regardless of the cause, are good for Canada. Rather than debate their utility, we should focus on how we can minimise the pain of the inevitable adjustment and maximise the benefits of our resource economy for all Canadians.

This really shouldn’t be that hard to understand.