China hits the hardwood

By signing deals with NBA stars, upstart Chines shoemakers aim to crack the U.S. market

Share

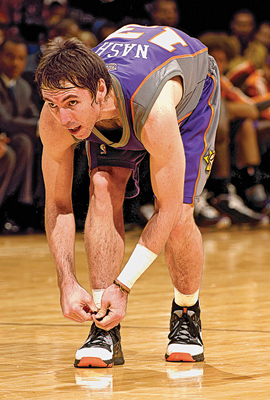

In early January, as the Phoenix Suns basketball team struggled to turn around a disappointing season, two questions surrounded point guard Steve Nash—would the team trade him to another city, and what’s with those Chinese sneakers anyway?

After a 15-year tie-up with Nike, the B.C. native announced he had signed a sponsorship deal with Chinese shoemaker Luyou. It wasn’t a complete switch. Nash will still wear his old Nikes on U.S. courts, while he’ll lace up in his Luyous on trips to the Middle Kingdom. But as Chinese shoemakers stomp into the U.S. market, they’ve determined the two keys to success are a lookalike Nike-style swoosh logo, and an endorsement deal with a major NBA athlete.

Over the past couple of years, some two dozen NBAers have stepped into Chinese brand shoes. The Boston Celtics’ Shaquille O’Neal sports Li Ning sneakers. His teammate Kevin Garnett wears shoes from a company called Anta. Meanwhile a number of rookies, including Patrick Patterson of the Houston Rockets, have signed with Peak Sports. Unlike Nash, most of the players wear their Chinese sneakers during games. And while the overwhelming majority of fans will have never heard of any of those brands, the companies are banking that will eventually change. “A brand doesn’t exist anywhere but inside the minds of the customers,” says Joe Benson, a brand strategist with Brand Blueprint in Boston. “What the Chinese want Steve Nash to do is bring in some positive associations with the sneakers.”

The moves are part of a push by Chinese companies to establish identifiable global brands. On the surface, the sneaker business seems perfectly suited to the task. Western consumers already know American-brand sneakers are all made in China, quite possibly in the same factories and by the same workers as those of the new Chinese brands. The deals with pro athletes are the first step to getting the shoes onto store shelves in the U.S. Last year, Li Ning—a company launched by a former Olympic gold gymnast of the same name—opened its first U.S. retail store 20 minutes down the road from Nike’s headquarters in Portland. In 2009, Li Ning reported sales of $1.3 billion and has more than 7,000 stores in China.

What’s more, with basketball hot in China, thanks to Houston Rockets centre Yao Ming (who incidentally wears Reeboks) the sponsorship deals will help the companies with their sales there, too.

Still, endorsement deals have their limits, says Benson. For one thing, Western customers may not know how to spell or even pronounce the Chinese names—a similar challenge to what Toyota faced in the 1970s. The companies, for their part, face the difficult task of deciphering and navigating fickle Western consumer attitudes. Meanwhile, the China brand itself carries much negative baggage in America these days.

The race by the Chinese companies to win over American basketball fans certainly hasn’t been without its stumbles. In English translations, Luyou’s slogan—”I think. I can”—is missing the period, prompting jokes and comparisons to The Little Engine That Could. A far more damaging episode occurred last year when Los Angeles Lakers forward Ron Artest noted he was suffering from sore feet. Head coach Phil Jackson blamed Artest’s Peak shoes, saying they were like “concrete boots . . . made for the Hudson River.” Artest, who had signed an endorsement deal, shot back on Twitter: “Coach Phil Jackson made a statement that my shoes are the reason my feet were hurting. He has no evidence. I love my shoe company. Peak.”